Brazil’s right-wing President-elect Jair Bolsonaro thinks that scripture tells Brazilians to arm themselves. “Paul says, ‘sell your cloak and buy a sword.’ It’s in the Bible,” Bolsonaro told reporters in August. “In those days there were no firearms. If there had been, it would have certainly been a 50 caliber machine gun.” (Incidentally, Bolsonaro got Paul and Jesus confused. This quote is from the Gospel of Luke 22:36.)

Given that the evangelical Christian right has long played a central role in conservative politics in the United States, some readers may be surprised to learn that a unified evangelical front is a relatively new force in Latin America.

Across the region, evangelicals are increasingly mobilizing for conservative candidates and causes. In Colombia, for instance, they helped defeat the 2016 peace referendum. And in Costa Rica and Chile in recent years, evangelicals suddenly sprang from quiescence into action when faced with the imminent threat of the legalization of gay marriage and abortion rights. In Brazil, a fear of what has been called “gender ideology” fired up the religious vote that in turn contributed to Bolsonaro’s victory on Oct. 28.

Latin America has long been overwhelmingly Catholic, and the church has sometimes played a role in politics. But evangelical Christians now account for about 19 percent of the region’s devout, according to the Pew Research Center, and experts project that the figure is 30 percent in Brazil.

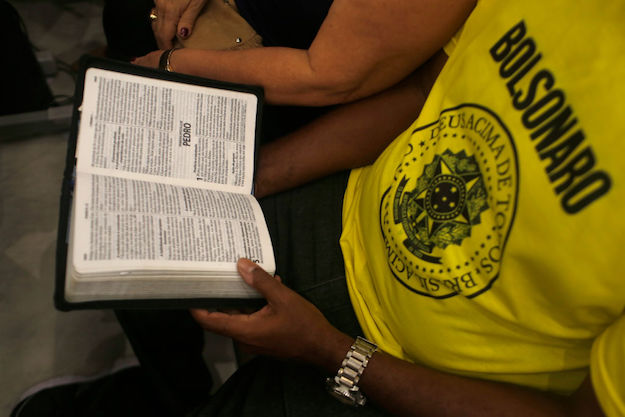

Pentecostal churches strongly backed Bolsonaro during the presidential campaign, capping a wave of activism that has been slowly building since Brazil’s 1986 elections for the constitutional assembly. Polls showed that, compared to Catholics, evangelicals supported Bolsonaro by a margin of 10 to 20 percentage points. Bolsonaro also stacked up an impressive set of endorsements from evangelical and Pentecostal leaders, who virtually ignored his Pentecostal opponent Marina Silva.

Demonstrating his deep ties to the evangelical community, Bolsonaro’s first public act following his victory was to attend a worship service led by the celebrity pastor Silas Malafaia. His hands laid on Bolsonaro in prayer, Pastor Malafaia cried, “We’re going to have a new paradigm in this nation. God will change the fortune of this people … Brazil belongs to Lord Jesus.”

Though Bolsonaro identifies as Catholic, he is married to an evangelical, attends a Baptist church, and was baptized in the Jordan River by a prominent evangelical leader. His acceptance speech on the night of the election included a prayer on national television, a first for Brazil.

Brazil’s evangelical politicians have traditionally performed better in legislative races, where open list proportional representation electoral rules mean that candidates do not have to win a majority of the vote. The congressional evangelical caucus, formed in 2003, will jump to 91 members in the congress installed in 2019. But the election of evangelical bishop Marcelo Crivella as mayor of Rio de Janeiro in 2016 demonstrated evangelicals could also win executive office.

In the Brazilian presidential election, some of Bolsonaro’s supporters followed his lead, invoking the Bible to justify violence. Take Bolsonaro’s enthusiasm to resuscitate the reputation of Brazil’s 1964–1985 military regime. One Bolsonaro supporter on social media invoked a popular insult to imply critics are communist psychopaths, or “esquerdopatas”: “They don’t even know that Jesus favored torture too! So much that he was tortured and accepted it without complaining! … Those communists need to read the Bible more.”

What is driving the increased participation of evangelicals in politics? And what does it mean for democracy in Latin America?

We can quickly dismiss three possibilities. The rise of Latin America’s new evangelical right is not an automatic result of citizens’ conversion to evangelicalism. Any organizer will tell you that numbers help. Still, Latin American evangelicals have often been content to stay out of politics. An old saying among Brazilian evangelicals once held that, “Believers don’t mess with politics.”

Nor is the rise of the Latin American evangelical right primarily a result of influence from North American activists. Though many evangelicals have cross-national ties, the most important leaders and their funding are local.

And finally, Bolsonaro’s threatening rhetoric about crime and minority groups seems on average to have turned off more evangelicals than it attracted.

Instead, a backlash against the perceived liberalization of traditional family and gender roles has sparked rapid and fierce political action among Latin America’s evangelicals. In the Brazilian campaign, fallacious viral rumors circulated through WhatsApp messages in evangelical communities, accusing Bolsonaro’s opponent Fernando Haddad of supporting sexual education programs that would manipulate young children to become gay or transgender. Anger over what evangelicals call “gender ideology” has fused with intensifying opposition to Haddad’s center-left Workers’ Party.

What is the upshot for democracy?

For those of us who believe in Latin American democracy, evangelical mobilization contains good news. Studying Brazil’s 2014 election, I found that evangelical clergy strongly supported democracy in the abstract – and they communicated those attitudes to their congregants. Over the past few decades, evangelicals have campaigned for candidates on both the right and left. This engagement may have given otherwise-alienated citizens a personal stake in the political system.

But there is also growing reason to worry. Many evangelical clergy think the political system threatens evangelical interests. And when evangelical clergy feel that way, their congregants become less supportive of democracy. Viral fictitious stories about the government forcing children to be transgender certainly contribute to this democratic anxiety.

Brazil shows us the playbook of the new Christian right in Latin America. Coalitions between rightist politicians and evangelical and Pentecostal groups are likely to be anchored in mutual opposition to liberal ideas about gender and sexuality. Evangelicals are invested in democratic tools and methods of electoral politics to defend their beliefs. The question remaining: What about the rightist politicians who are their political allies?

—

Amy Erica Smith is associate professor of political science at Iowa State University, and author of Religion and Brazilian Democracy: Mobilizing the People of God (2019, Cambridge University Press). Her research focuses on public opinion and political culture in Latin America, and particularly Brazil.