BOGOTÁ – Iván Duque’s need to prove himself to more radical elements of his base continues to undermine his chances of success as Colombia’s president.

For a third time since taking office last August, Duque has called for a “National Pact” to help untie the Gordian knot of Colombian politics. He hopes to draw support for reforms to the beleaguered judicial system and for amendments to the FARC peace agreement, both of which are stuck in Congress and the courts.

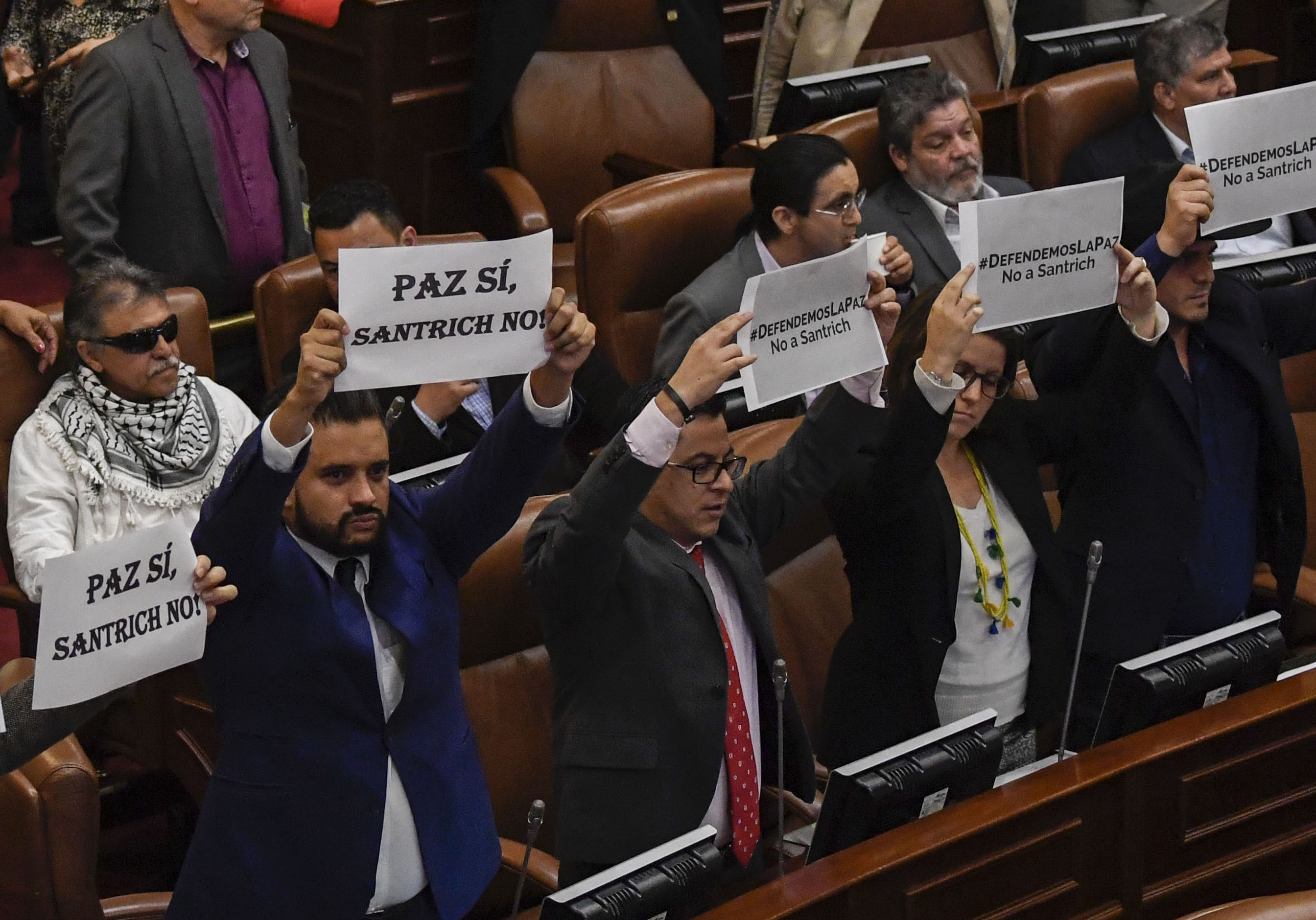

Duque’s call comes after weeks of tumult and political intrigue that included the resignation of Attorney General Néstor Humberto Martínez in response to the release from prison of a former FARC commander, Jesús Santrich. An accord with the opposition might help Duque calm rough waters.

But his inability or unwillingness to push his own party to compromise could doom the effort.

The president has tried the idea of a national pact twice before. While the most recent, in support of his national development plan, bore some fruit, the first, on a series of anti-corruption measures, failed to have its desired effect in the legislature. That was in part because Duque’s Democratic Center party refused to support legislation that originated with the opposition. Duque’s effort this time around appears destined for a similar fate.

As before, the biggest obstacle for Duque to bring the opposition onboard lies in his own party. Rather than work with opposition parties on their priority issues (such as infrastructure spending, rural reform and anti-corruption measures), the Democratic Center in Congress has been adamant in first modifying the peace agreement and the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a court set up to try those implicated in crimes during the country’s conflict with the FARC.

This is a non-starter for some independent and opposition parties. Even those that have taken a more moderate position toward the government, such as the U Party and the Liberal Party, have made clear that in order to push for modifications to the peace agreement, the opposition must be included in negotiations.

But Duque and his allies seem to equate national unity with acquiescence to their agenda. His administration has limited the space for compromise by insisting that government bills be passed without modification, ostensibly to avoid legal or legislative setbacks.

Ultimately, some opposition parties like Radical Change may reach agreements with the government on specific legislation, such as reform to the country’s general system of royalty payments. But as long as the administration fails to find mechanisms for taking opposing views into account, even moderate opposition parties are unlikely to join a coalition or endorse the agenda proposed by the Democratic Center.

National unity is all the less likely given Duque’s position ahead of local elections in October. Opposition parties are in no mood to do favors for an unpopular government – Duque’s approval rating has decreased steadily from 43.2% in March to 31.6% in May, according to data from Colombia Risk Analysis’ Presidential Favorability Monthly Index (IMFP).

Indeed, this unpopularity is in part a product of Duque’s insistence on Congress taking up his objections to JEP, as well as other modifications to the peace agreement. The government’s debate on these ideas has stagnated legislative debates on other topics, as it has consolidated independent and opposition groups who support the peace agreement against the government’s efforts.

Whether or not Duque intended to make altering the peace accord a centerpiece of his first year as president, he now finds himself beholden to a political base that would gladly turn on him if he doesn’t meet their demands. Spurred on by the Democratic Center, the administration has further alienated its opponents by floating the possibility of convening a National Constituent Assembly or calling a state of emergency to pass some government initiatives by decree.

Rather than move his party toward compromise, Duque has moved toward his party. That may have shored up Duque’s support in the short-term, but it has also limited his chances of broader success. The president’s intention to bring the country together through a National Pact is a worthwhile endeavor. But the logic with which the government is approaching it will only solidify political division.

—

Guzmán is the Director of Colombia Risk Analysis, a political risk consulting firm based in Bogotá. Follow him on Twitter @SergioGuzmanE and @ColombiaRisk