An odd weather report was published on December 14, 1968, in Jornal do Brasil, at the time one of the largest circulation papers in the country.

Weather forecast – dark times

Temperature – suffocating

The air is unbreathable

The nation is being swept by strong winds

It was actually the news, and the only way possible to convey it. The night before, in a televised address to the nation, the justice minister of the military dictatorship ruling the country since 1964 had announced the enactment of the “Institutional Act Number 5”. The AI-5, as it became known, superseded the constitution and ushered in a new, more oppressive phase of the regime. The newspaper’s “weather report” was a way of editorializing about the change without provoking the military’s censors.

Institutional Acts established supra-constitutional powers and legalized actions by the Brazilian military rulers. The first one was signed on April 9, 1964, just days after civilian president João Goulart was deposed. AI-1 gave the regime the power to terminate terms of elected representatives and strip critics of all political rights, as well as to fire any civil servant on national security grounds. The following year, the Institutional Act Number 2 (AI-2) instituted indirect elections for the presidency, extinguished political parties and honed the system of persecution of opposition figures by giving the general-president the right to declare a state of siege without congressional approval.

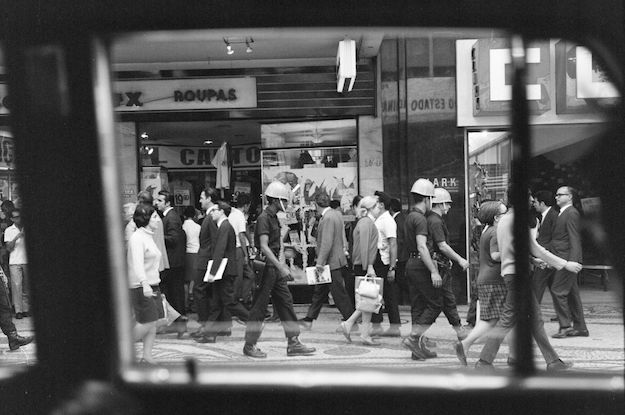

By the time the fifth act came around, it was 1968 – a year that became a symbol thanks to a series of transforming events around the world. The mobilizations against the Vietnam war, the hippie movement, the sexual revolution, the large demonstrations in Paris, Berkeley, Berlin, Mexico—there was transformation in the air in all fields of existence: in politics, in culture, in the arts. In Brazil, the winds of rebellion were blowing under a dictatorship.

In Rio de Janeiro, 100,000 students took to the streets marching against the repressive regime. All over the country universities and secondary schools started to mobilize, even though they were met with violent repression. In September 1968, elected representative Márcio Moreira Alves spoke on the house floor against the invasion of the University of Brasilia by the Military Police, even suggesting girls should refuse to dance with soldiers until the dictatorship was over. The executive branch asked the Supreme Court to terminate Alves’ mandate, but in a session on Dec. 11, the lower house refused to comply with the order to expel Alves. The AI-5 was signed two days later.

The fifth Institutional Act marked the beginning of the hardest phase of the military dictatorship. Enacted by then President Marshall Artur da Costa e Silva, it gave the regime exceptional powers against all forms of opposition or criticism of military power.

That same night, after the Justice Minister’s televised address to the nation, the military shuttered Congress and detained major opposition figures– including former civilian president Juscelino Kubitschek (1956-1961), arrested leaving a theater in Rio de Janeiro.

In the following year alone more than 300 politicians had been expelled from Congress. Supreme Court justices were taken from the bench and dozens of university professors were arrested or sent to exile, including Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who would become president decades later.

Harsh censorship rules were imposed, leading newspapers to improvise, communicating through the odd weather report in Jornal do Brasil to cake recipes, poems or just blank pages.

AI-5 gave the dictatorial regime legal powers to close not just Congress, but state assemblies and city councils. The regime could deny habeas corpus for political crimes, take away the political rights of any citizen for 10 years, and confiscate property. Brazilians arrested on suspicion of subversion and arrest did not have the right to communicate with anyone during the first 10 days of arrest. That silence period left prisoners without any legal protection. During those 10 days, no one– neither family nor lawyers – had any right to any information about the person: where they were held, their physical integrity or even if they were alive.

The AI-5 forbade any form of political demonstration. Censors became permanent fixtures in newsrooms. Shows, plays and cultural events had to be vetted by censors. While repression and persecution had existed since the beginning of the dictatorship in 1964, the AI-5 installed a true terrorist state, increasing the practice of torture, deaths, executions and disappearances.

It is important to remember that the AI-5 was followed by other acts that further hardened the government’s dictatorial character. One act, AI-13, institutionalized the banishment or deportation of any citizen that was considered bad for the regime. Another, AI-15, expedited the death penaty, unless the president commuted sentences to life in prison.

Despite these efforts, the military regime’s excess force never completely silenced dissent. In 1978 the government’s “opening” process struck down the Institutional Acts. Ten years later, the 1988 Constitution was written in the shadow of those dark years of state-sanctioned repression and persecution. Now, as we hear loud voices around the world questioning democracy and even clamoring for authoritarianism, it is more important than ever to listen to this lesson from the past.

—

Dornelles was a member of the Rio de Janeiro Truth Commission. Currently, he is a professor at the Graduate Law Program at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. He is also a member of the Brazilian Association of Jurists for Democracy and the National Association of Human Rights Research and Graduate Programs.