For most Brazilians, the disaster unfolding in neighboring Venezuela is little more than another passing topic on the evening news. The daily protests in Caracas are more than 2,500 miles away from São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, cultural ties between the two countries are limited, and the current political and economic crisis in Brazil reduces the airtime reserved for discussing foreign affairs even more than usual.

Not so in the Brazilian state of Roraima and its capital Boa Vista, the country’s only state capital north of the equator, where Venezuelans fleeing violence, poverty or the lack of even basic medicine have become a common sight – at the city’s intersections, washing windshields, selling sweets or simply asking for some change.

“Things really changed over the past year in Boa Vista,” one cab driver told me during a recent trip to the border region to study the growing number of refugees. “There are prostitutes in the streets, offering their services in broad daylight, for all the children to see,” he says, pointing in the direction of the neighborhood popularly known today as Ochenta, or “Eighty,” a reference to the price supposedly charged by Venezuelan sex workers close to the city’s popular food market.

Such views are commonly heard in Roraima, but tend to exaggerate the negative impact of refugees, says Julia Camargo, a professor of international relations at the Federal University of Roraima who studies the topic. There is no hard evidence that the growing number of Venezuelans has led to an increase in crime. But the influx has posed clear challenges for a country that takes pride in its centuries-old image as a welcome refuge for immigrants, but is also straining under rising unemployment and its worst recession in at least 100 years.

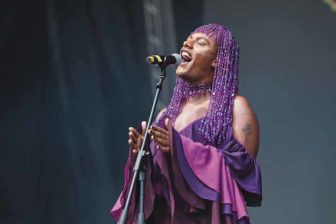

A Venezuelan performs at an intersection in Boa Vista, Brazil.

A Venezuelan performs at an intersection in Boa Vista, Brazil.

Estimates of the number of Venezuelans in Brazil vary greatly. The Federal Police estimates that there are between 15,000 and 20,000 Venezuelans in and around Boa Vista today, even though many think the number is higher, as it is fairly easy to cross the border without documentation. This is far less than the number of Venezuelans who have entered Colombia over the past years – one estimate by Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar University put that number as high as 900,000.

Yet it is no small number for a relatively quiet town of 325,000 that has never faced anything comparable. There have been few instances of overt xenophobia and many businesses have offered a helping hand. Many waiters in cafés and restaurants hail from Venezuela. The 25-year old Rodrigo, who arrived last year from Puerto Ordaz and now serves drinks in a downtown restaurant, says customers often strike up a conversation and try to cheer him up when he complains about the situation back home. Local university professors have mobilized to offer classes for refugees, and to counsel sex workers and members of the indigenous Warao tribe, who used to live in Northeastern Venezuela.

Yet Camargo says there are numerous cases of exploitation of Venezuelan women working as maids, who receive little or no salary other than food and shelter, but who are afraid to contact the authorities since they have no legal authorization to work. Under Brazilian law, applicants only obtain a work permit once their asylum request is processed, which can take months.

While many in Roraima speak of an “invasion by Venezuelans,” most local residents do not blame the migrants themselves, but say the Brazilian government does little to help the region deal with the growing number of arrivals. Brazil’s Foreign Minister Aloysio Nunes recently visited the border, but, as a local university professor who studies the topic bemoans, “he didn’t take the time to speak to the people of Boa Vista. He could have taken one hour to come to the university auditorium and explain the government’s plan, if they have one.” As a consequence, many wonder what would happen if the number of arrivals doubled or tripled, a scenario not entirely unrealistic considering the ever-deepening crisis in Venezuela.

The state’s public health system, already overburdened and underfunded before the refugee crisis, has been hit hardest. This is because many Venezuelans arrive in Brazil with severe illnesses that require urgent and often expensive treatment, such as terminal cancer or complications related to tuberculosis, diabetes, HIV/AIDS and malaria that have been left untreated as there is practically no medicine available in Venezuela. According to a recent report by Human Rights Watch, 80 percent of patients treated in the hospital in Pacaraima hail from Venezuela.

On a quiet morning at the border, about 200 kilometers north of Boa Vista, a Brazilian border official says the Venezuelans come in waves, but says he does not know what explains the fluctuations. In the same way, it remains unclear why precisely hundreds of members of the Warao tribe decided to cross the border into Brazil, and whether more could come. This will be crucial for city hall, state and federal government to coordinate effectively.

Despite the concerns, there is little doubt that Venezuelans brought cultural diversity unknown to Boa Vista before. Guaka Guaka, a Venezuelan bar, is packed on weekends with Brazilian customers listening to Caribbean music. On a Saturday night, families taking an evening stroll on Praça das Águas, listen to the band Mariachis Sol de México. Five months ago, the group left their Venezuelan hometown of Valencia due to exploding levels of violence and food shortages and applied for refugee status in Brazil. “We want to work hard and hope the Brazilian people appreciate our music,” says Saúl, the band’s trumpeter.

Mariachis Sol de México, a Venezuelan band, perform in Boa Vista.

Mariachis Sol de México, a Venezuelan band, perform in Boa Vista.

There is a significant chance that the crisis in Venezuela will get worse before it gets better. Boa Vista should brace itself for more Venezuelans. The Brazilian government seems unlikely at this stage to devise and fund a clear strategy, which could include, for example, offering public schools help dealing with the influx of children who do not speak Portuguese. The disorder resulting from a lack of clear policies will make some local residents more vulnerable to xenophobic candidates such as Jair Bolsonaro in next year’s presidential election. Mainstream politicians must respond forcefully and point out that in the medium and long term Brazil will not only succeed in integrating the newcomers, but also benefit from their presence – as it has done for centuries.