In recent years, Brazil has encountered a health threat more commonly seen in the advanced industrialized nations: obesity. The emergence of fast-food diets, sedentary lifestyles, as well as federal programs designed to alleviate malnourishment has—rather ironically—contributed to the nationwide spread of obesity.

A survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, which interviewed 54,000 adults across Brazil from January to December 2011, found that the percentage of overweight individuals increased from 42.7 percent in 2006 to 48.5 percent in 2011. Rates of obesity, on the other hand, increased from 11.4 percent to 15.8 percent over the same time period.

Despite incessant scientific warnings, the government has not launched an impressive campaign to address this issue. In large part this has to do with the ongoing belief that hunger and malnutrition are still Brazil’s biggest problem. What’s more, in the absence of international pressures and financial resources to help prevent obesity, there have been few incentives for politicians to do so. But on the heels of its hosting the Rio+20 Summit last week and its discussion of environmental safety and the over-consumption of goods, Brazil now has an opportunity to impress other nations with a much-need response to a growing epidemic.

Since the mid-1990s, the emergence of the fast-food industry in Brazil as well as easy access to cheap foods has contributed to the growth of obesity and other related diseases. Obesity’s rise has also been facilitated by the increased usage of computers, televisions and the Internet, in turn contributing to sedentary lifestyles. The growth of less physically demanding jobs (increasing from 29 percent in 1970 to 55 percent in 1999) and the increase in working hours—with the resulting effect that parents have little time to cook healthy meals—have further contributed to high obesity rates, even among the poorer socioeconomic classes.

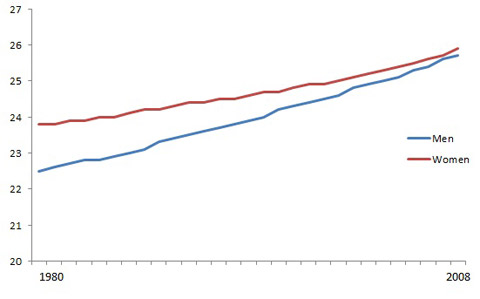

estimated mean body mass index in brazil, 1980-2008

Source: World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory Data Repository (2012)

Intriguingly it also seems that Brazil’s antipoverty programs have contributed to obesity’s rise. In 2003, for example, then-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva created Fome Zero (Zero Hunger), a program that provides approximately $20 a month to poor households in order to purchase food. With this money, however, the poor have largely been buying fatty foods that are easier to access and cheaper, especially when compared to more expensive vegetables.

One result is a greater incidences of diseases closely associated with obesity, such as type-II diabetes, heart disease and cancer, which account for roughly 41 percent of total health care costs. So, what has the government done in response?1

Not much. A federal nutrition program was created in 1999 to help provide healthier foods to schools, and legislation was passed in 2001 to regulate nutritional food content and the labeling of canned goods.2 In 2003, the Programa Saúde na Escola was created to provide schools with agricultural foods. Still, local governments have largely been left to respond on their own.3 In recent years, no new federal programs have been authorized to help the states respond to the growing obesity levels.

The federal government instead continues to see hunger, not obesity, as Brazil’s biggest nutritional problem. This has led to the creation of a federal Centre for Excellence Against Hunger in November 2011, an endeavor that helps other nations combat hunger in schools. But with the government’s excessive focus on hunger, it will be difficult to muster the political support needed to create bolder anti-obesity programs.

What’s more, as a nation sensitive toward its international reputation, especially in the area of public health, the absence of international criticism around Brazil’s lackluster response to obesity, as well as the lack of international funding to address this issue, has created few incentives for the government to strengthen its response. In large part this is linked with the absence of international consensus within the World Health Organization that responding to obesity and diabetes is of paramount importance.

Nevertheless, last week’s Rio+20 environmental summit may provide a turning point in Brazil’s response to obesity. In general, the summit focused on issues that could keep the world from consuming itself into an environmental and economic disaster such as the need to address climate change, the loss of biodiversity and safeguarding natural resources. Participants also discussed the need to eradicate hunger as well as to regulate the over-consumption of scarce foods.

Brazil should use its increasing global clout to help lead the international community in minimizing the health consequences of over-consumption and obesity. Given the government’s historic tradition of preventing the spread of other diseases and eradicating hunger, it would behoove the administration of President Dilma Rousseff to put just as much effort into reducing its ongoing obesity problem. Failure to act now will only bring greater long-term health challenges.

1 See Rosely Sichieri, Sileia do Nascimento, and Walmir Coutinho. 2007. “Importancia e custo das hospitalizações associadas ao sobrepeso e obesidade no Brasil,” Cad. Saúde Pública 23(7): 1725.

2 Monteiro et al. 2002. “Is Obesity Replacing or Adding to Under-nutrition Evidence from Different Social Classes in Brazil,” Public Health Nutrition 5(1A): 105-112.

3 See C. Reis et al. 2011. “Políticas públicas de nutrição para o controle da obesidade infantile,” Rev Paul Pediatr 29(4): 625-333; and see See Denise Coitinho, Carlos Monteiro, and Barry Popkin. 2002. “What Brazil is doing to promote health diets and active lifestyles,” Public Health Nutrition 5(1A): 263-267.

Homepage photo courtesy of Stuart Anthony.