Venezuela has been on a wild ride since Hugo Chávez was elected president in 1998. Now that the Comandante—as he liked to be called—has left us, things could get loonier a lot faster. That’s one reason why Caracas Chronicles, an English-language blog that has provided a running narration since 2002 of the Chávez era, will continue to be an indispensable tool of analysis and information for addicts of the Chávez story—a story that so far has managed to outlive the flamboyant president.

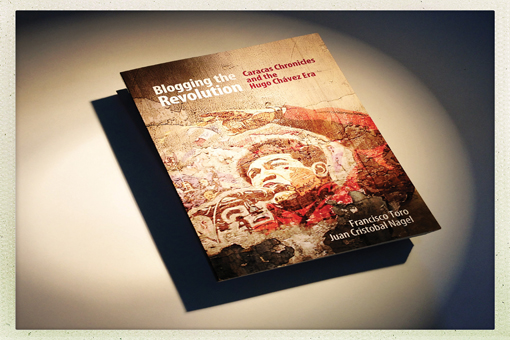

With the death of Chávez and his spectacular funeral still fresh in the collective memory, the publication of Blogging the Revolution: Caracas Chronicles and the Hugo Chávez Era, a compilation of some of the blog’s best postings, is well timed. It provides an opportunity to look back on the past and to meditate on the future of Venezuela as it teeters between comedy and tragedy. This is an essential read for anybody interested in Venezuela.

The primary audience of both the book and the blog appear to be bilingual professional Venezuelans, many of whom have left the country. The authors are members of this group: Francisco Toro, a political scientist who lives in Montreal and Juan Cristobal Nagel, an economist who lives in Chile. Their blog benefits both from their frequent visits home and their close contacts with sources inside the country, combining keen analytic abilities with a cool reportorial style. But apart from Venezuelan émigrés, Caracas Chronicles attracts readers drawn to the region’s most interesting stories of the past decade.

The book features only a small number (about 100) of the more than 6,000—and counting—posts published over the past 11 years. But the vignettes capture the reality of the Chávez era, ranging from daily life events to the period of sometimes violent confrontation between chavistas and anti-chavistas.

The postings in the first section are essential for anybody who wants to get beyond what the authors call the “static chaos” of Venezuela since Chávez came to power. The authors regularly return to a key theme: how Venezuela’s politics and psychology have been shaped by the discovery of the country’s enormous oil resources early in the twentieth century, and by the resulting patronage machine.

As the authors suggest, oil riches also translate into the “magical thinking” that permeates Venezuelan society. A part of that magical thinking is the deeply held belief by many Venezuelans that despite the inability of oil money to keep up with population growth, the country is fabulously wealthy and the state’s only job is to redistribute the wealth, making all Venezuelans rich. “In the end, breaking the petrostate as [a] social system is child’s play compared to the monumental task of breaking the petrostate as an idea,” writes Toro.

Also, the authors tackle the question of why Venezuela remains polarized. A blog post titled “Towards a critical theory of Chavismo” draws on the work of Venezuelan intellectual J.M. Briceño, who posits that Venezuelans and Venezuelan culture have three co-existing types of discourse: a rational Western one; a colonial authoritarian one; and a “savage” discourse stemming from the wounds left by the Spanish conquest and African slavery. This third mindset, which amounts to nostalgia for a non-Western way of life, considers the European rationalist critique common to most of the Chávez opposition as profoundly oppressive. Chávez’ ability to exploit this both infuriates and baffles the opposition, who are reluctant to admit, says Toro, that this non-Western tradition strikes a deep chord with millions of Venezuelans for whom Chávez served as a spokesman.

Not to be overlooked are the many funny, well-reported profiles of Venezuelans that illustrate the contradictions and absurdities of everyday life in this allegedly revolutionary country. On one occasion, Nagel goes to a seminar where chavistas must listen to humorless officials as they try to define Bolivarian socialism. One chavista says he is ready to let go of capitalist tastes such as eating at McDonald’s. A line is drawn, an alarm is sounded. Groans arise from the audience, and a woman behind him mutters “Don’t mess with MacDonald’s. I like my McNuggets.”

Nowhere in the annals of human history has so much revolutionary rhetoric about the awfulness of the rich coexisted so peacefully and happily with over-the-top conspicuous consumption as in the Chávez era. This is true for the Boliburgueses, the new class of politically connected chavista businessmen who have made millions and in some cases billions of dollars from a state that is breaking all previous records for corruption and opacity. And it is also true for the many Venezuelans who manage even today to make lots of money by gaming currency controls and arbitraging dollars. Under Chávez, Caracas was a place where one could attend a Byelorussian fashion fair one day, and on the next day watch huge cartoon-like hot-air Chávez figures tower over the city, as in a Venezuelan version of a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. Many of the blog postings capture these at times surreal scenes. One night, Nagel takes readers to a lavish wedding in red Caracas. Champagne flows all night. There is a sushi bar and a Chinese chef. Astounded at the luxury, Nagel asks himself: “In what chapter of Das Kapital is the bit about the sushi bars?” A friend tells him this is nothing compared to a Boliburgués wedding where the bride’s mother had demanded furniture be brought in from Paris to set the right tone.

There is a lot more. A long post dissects the traumatic events of April 2002, when Chávez was forced out of the Miraflores Palace, only to return to power three days later. The post, acknowledging the work of journalists who minutely investigated the series of events, performs a great service in helping to understand this crucial episode. The authors may be unashamedly anti-chavista, but they are unsparing in their analysis of the opposition’s foibles, mistakes and painful triumphs. The book, like the blogs that inspired it, is a labor of love. One hopes that Venezuelans, and everyone else interested in the fate of the country, will continue to be served by the entertaining and insightful dispatches of Caracas Chronicles.