Brazil | Colombia | Costa Rica | Mexico | Paraguay | Venezuela | Cuba

See above for a breakdown of the region’s other 2018 transitions, or click here for the full list from our print edition.

Election date: July 1

Format: One round. The candidate with the largest share of the popular vote will be declared the winner.

Ricardo Anaya, 38, former party president

Ricardo Anaya, 38, former party president

National Action Party

“The PRI is desperate … and it’s trying to divide the PAN.”

How he got here: This “boy wonder” got his political start at 21, when he ran for the state legislature in Querétaro. Now 38, he resigned his leadership of the National Action Party (PAN), to run for president with Forward for Mexico (Por México al Frente), an ideologically diverse coalition of opposition parties.

Why he might win: He’s a talented political strategist. Under his leadership, the PAN won big in the 2016 midterm elections, snagging seven of the 12 gubernatorial seats that were up for grabs, including in states considered PRI strongholds.

Why he might lose: He has lost potential allies and stands accused of damaging his party on the road to the top. Zavala’s departure from the PAN, in particular, will cost the coalition. Voters may be wary of his Machiavellian reputation.

Who supports him: PAN voters are generally middle class, well-educated, and most concerned about crime. Heading the coalition will force Anaya to court left-leaning voters from the Democratic Revolutionary Party and Citizens’ Movement.

What he would do: A proposed universal basic income was one of the coalition’s first specific policies, although it could amount to as little as $540 a year. It’s unclear how the coalition will square differing views on social policy.

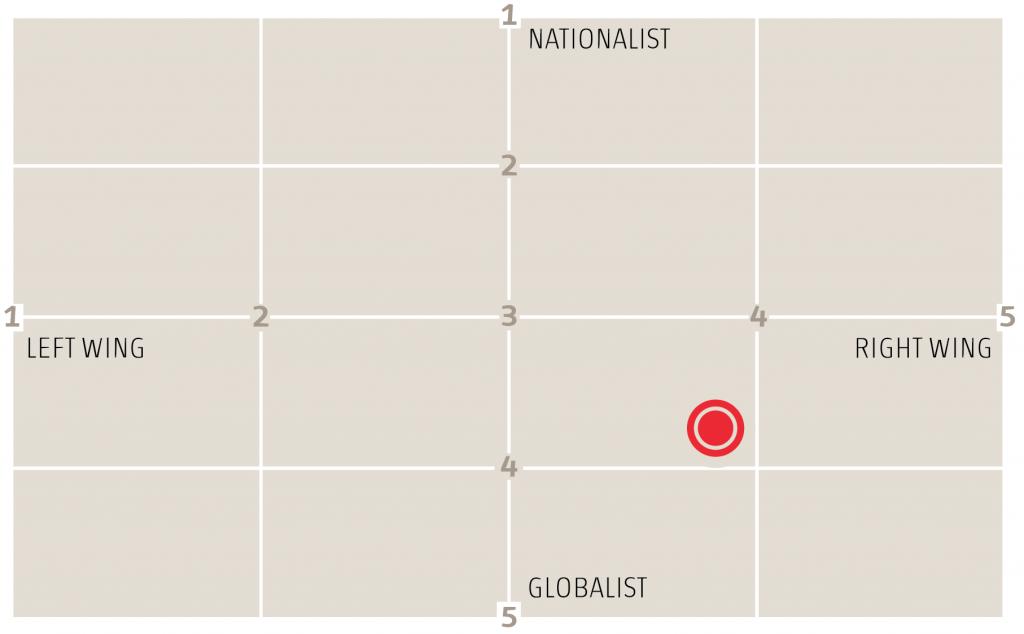

Ideology:

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 64, former mayor

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 64, former mayor

Morena

“We’re not against businessmen … we’re against corrupt politicians.”

How he got here: Will it be a third strike, or third time’s the charm for López Obrador? The populist former mayor of Mexico City, known colloquially as AMLO, narrowly lost presidential votes in 2006 and 2012. He is once again a front-runner heading into 2018 — and he says this election will be his last.

Why he might win: López Obrador has name recognition, and his long-running critique of the “mafia of power” should play well, given the anti-establishment mood. Roughly 80 percent of Mexicans see corruption as a major problem, and faith in public institutions is in steady decline.

Why he might lose: It’s happened before — twice. AMLO’s undisciplined rhetoric on the campaign trail has cost him votes. He drew criticism in December when, speaking in the violence-ridden state of Guerrero, he said he would consider amnesty for cartel leaders. Many of Mexico’s political and business elites are against him.

Who supports him: He does best with young, middle class, and well-off voters, particularly in the capital and his home state of Tabasco. His backers are tired of the status quo of lousy jobs and poor wages — and ready to try something different.

What he would do: AMLO has vowed to sell the presidential plane and cut ex-presidents’ pensions. He toned down rhetoric against the 2013 energy reform, saying he’ll evaluate rather than overturn it. Critics compare him to Hugo Chávez, but an opposition-controlled Congress might limit his more radical impulses.

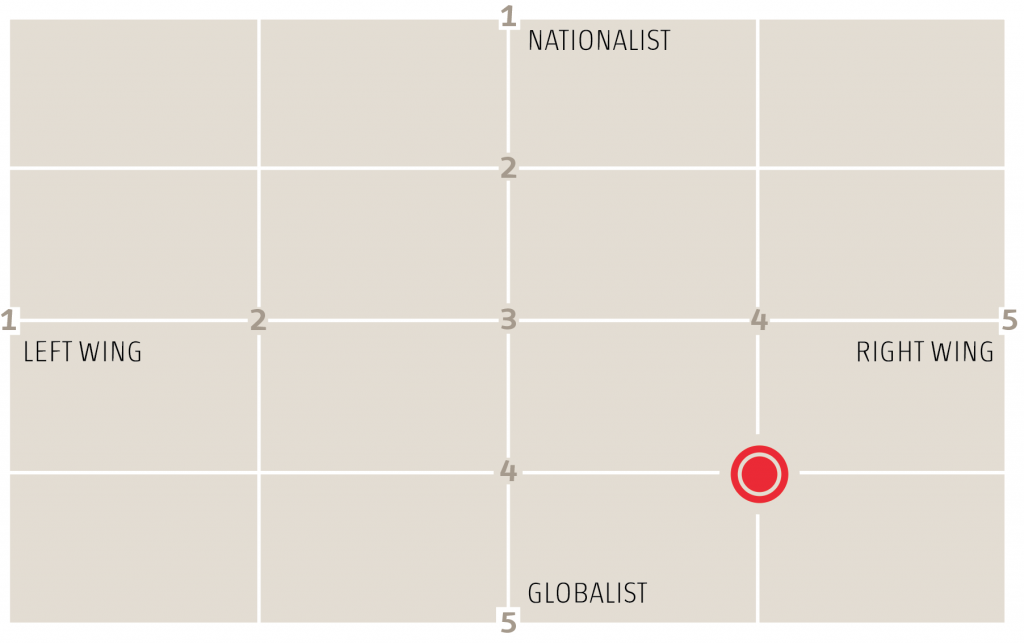

Ideology:

José Antonio Meade, 48, former minister

José Antonio Meade, 48, former minister

Institutional Revolutionary Party

“The country owes a great deal to the PRI.”

How he got here: Mexicans are tired of corruption, and no party is perceived as more corrupt than the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). One way to blunt that criticism is by running a candidate who isn’t a card-carrying member of the party. Meade — a technocrat who has served in both PAN and PRI governments — fits the bill.

Why he might win: He’s widely viewed as a capable administrator, and has held several top secretariat posts: foreign affairs, finance, social development, and energy. He’s never been elected to office, but he’ll have the country’s biggest, most effective political machine behind him.

Why he might lose: Meade isn’t a household name. He has never run for office, and many voters say they won’t vote for the PRI regardless of the candidate.

Who supports him: Many of Mexico’s political and business elites consider Meade to be the best candidate for the job. He could steal votes from the PAN, particularly among its more religious members (Meade is a devout Catholic). The country’s first PAN president, Vicente Fox, backs him.

What he would do: A vocal supporter of the reform agenda set out early in the Enrique Peña Nieto administration, he’d likely continue to open industry to competition and invite foreign investment in energy, telecommunications and other sectors. He also backs special economic zones as a way to develop the country’s poorer regions.

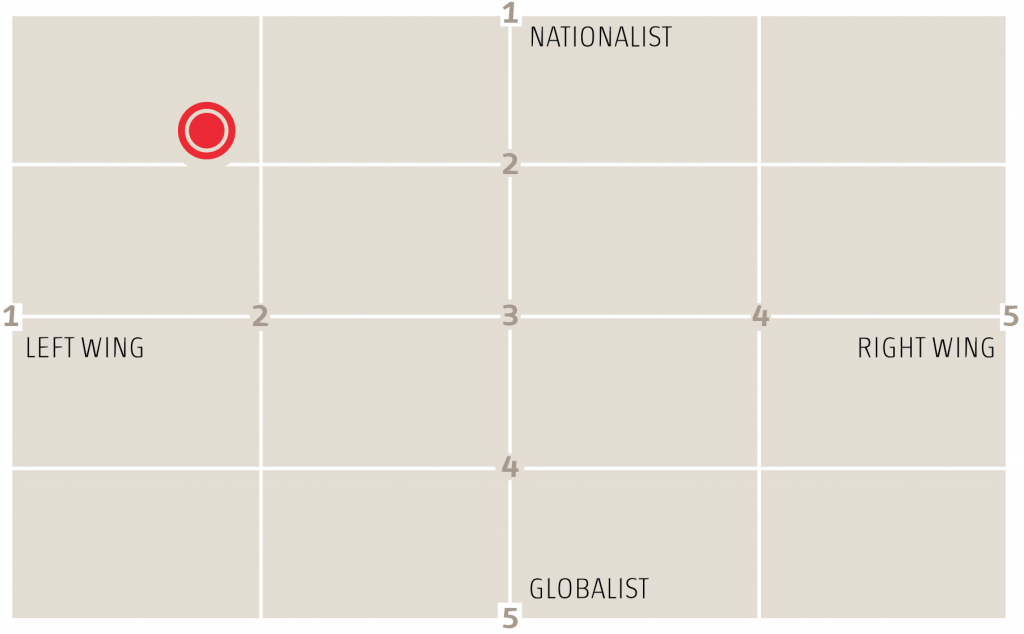

Ideology:

Margarita Zavala, 50, former first lady

Margarita Zavala, 50, former first lady

Independent

“When I become president, I will make the decisions having to do with my government. No one else.”

How she got here: The lawyer, women’s advocate and former first lady to Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) quit the PAN in October after 30 years as a member, claiming that party president Ricardo Anaya had denied her any opportunity at becoming its nominee. She’s running as an independent.

Why she might win: Zavala proved her ability to connect with voters in her time as first lady. She surpassed her husband’s popularity in the PAN, and still has the support of the party’s Calderonista faction. She’s a well-known national figure, and could be a major beneficiary if Anaya’s coalition is unable to hold together.

Why she might lose: Her husband started Mexico’s drug war, which may haunt her on the campaign trail — particularly as Mexico in 2017 experienced some of the highest homicide rates in its recent history. Zavala has never had to win a popular election (she became legislator on a party list) and it will be hard for her to break through without traditional party machinery.

Who supports her: Aside from the Calderón nostalgia vote, Zavala has more centrist and women supporters than most PAN politicians. She also does relatively well with young voters.

What she would do: She says violence and crime in Mexico persist because Peña Nieto “abandoned” the task of strengthening institutions after the drug war. She tends toward traditional PAN social views — including in her personal opposition to abortion.

Ideology: