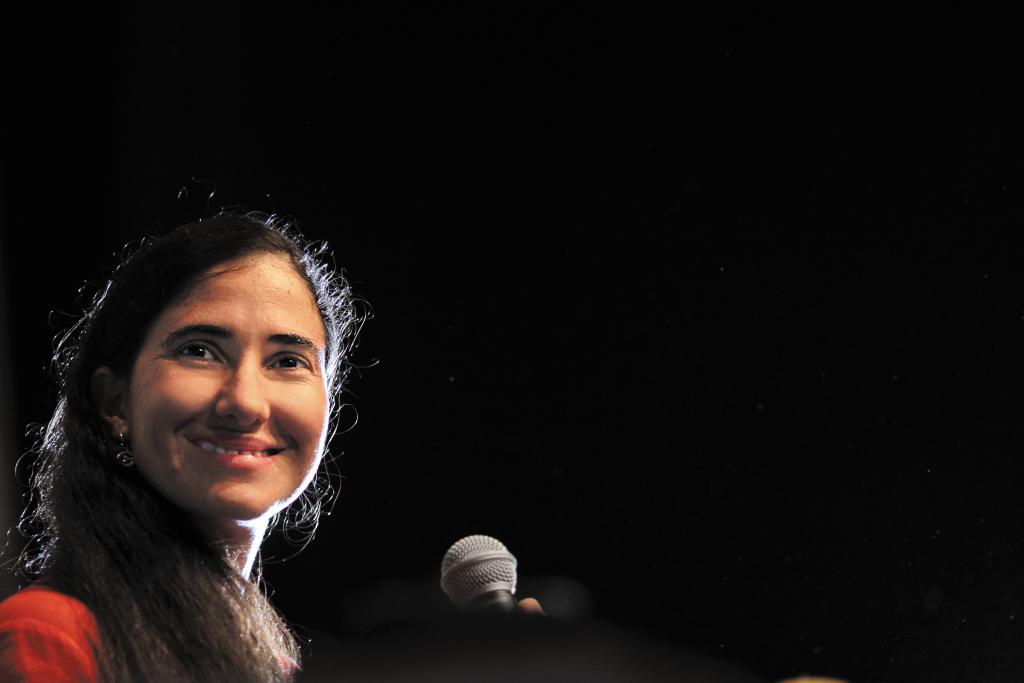

Yoani Sánchez smiles during a news conference that was part of her 80-day tour of South America, Europe and the U.S. in 2013. Photo: UESLEI MARCELINO/REUTERS.

Read profiles of:

By Michael Voss

Up from the provinces: Miguel Díaz-Canel waves to the crowds at the annual May Day march in Revolution Square in Havana. Photo: SVEN CREUTZMANN/MAMBO PHOTO/GETTY.

When Cuban President Raúl Castro appointed Miguel Mario Díaz-Canel Bermúdez as first vice president last year, little was known about the man who looks set to become the first Cuban leader in more than half a century who is not a Castro. He still maintains a low profile and is generally cautious in public pronouncements on domestic issues and foreign affairs.

As the most senior politician born after the Cuban Revolution, will Díaz-Canel ensure that Cuba’s socialist system survives once the generation that led the revolution fades into history?

The 54-year-old is a committed communist in the reform wing of the party. He worked his way up through the ranks of the party’s youth wing to become, at 43, the youngest-ever member of the Politburo, the Communist Party’s leading policy-making body. Raúl Castro has praised him for his “solid ideological firmness.”

Neither a charismatic leader nor a rousing speaker, Díaz-Canel is said to be witty and relaxed when dealing in private with small groups. His reputation is that of a socially liberal, experienced manager rather than an ideologue. Born in 1960 in the central province of Villa Clara, he was a Beatles fan, growing his hair long in the days when Western pop music was considered decadent. He studied electrical engineering, and in 1985 began teaching at Villa Clara University while he was forging a political career. In a few short years, he rose from head of the provincial Unión de Jovenes Comunistas (Young Communists League—UJC) to second-in-command of the national organization.

Before long, he was working his way up through the Communist Party. In 1994, at the age of 33, he was promoted to first party secretary of Villa Clara province and given a seat on the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Provincial party secretaries are one of the few jobs in Cuba that carry real power and responsibility. They are the local “czars” who must manage budgets and keep the local infrastructure and economy working.

Díaz-Canel arrived in Villa Clara at an auspicious moment. It was the height of the Special Period in the mid-1990s when, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Fidel Castro allowed the establishment of a limited private sector and opened the island to tourism. Many local residents still remember Díaz-Canel as a breath of fresh air, a man of the people who rode a bicycle around the town. What he lacked in charisma he made up for with his ability to listen.

His effectiveness persuaded authorities to send him to Holguín province as first secretary in 2003, where there was resistance to the party’s economic modernization program. He was also appointed to the Politburo, providing him with the added authority to take on the vested interests of the local party. In 2009, he was given another difficult mission as minister of higher education, where his introduction of tougher university entrance exams and upgrading of teacher training courses reversed years of slipping standards.

In 2012, he became a vice president on the Council of Ministers, and a year later, Raúl Castro promoted him to first vice president. As the heir apparent, Díaz-Canel entered the limelight just as Castro launched the first major update of Cuba’s Soviet-style economic model, decentralizing decision making, opening the doors to foreign investment and allowing Cubans to open small-scale private businesses. Although Díaz-Canel’s portfolio does not include the economy (he is in charge of education, culture, sports, and the press), he offered an early indication of his unflinching approach to change. “We’ve made progress on the issues that are the easiest to solve,” he said shortly after taking office, “and now what’s left are the more important and complex choices.”

He has spoken of the need for a more open and critical press and for allowing people greater access to news in the digital age. “Today, news from all sides—good or bad, manipulated and true—gets to people. They know [what’s going on],” Díaz-Canel told a higher education conference. “And what is worse, then? Silence?”

He has also displayed a notable openness to changing social values. When he was running Villa Clara, he allowed the country’s first gay nightclub to remain open, and he has since supported LGBT legislation such as including sexual orientation in an anti-discrimination clause in the new Labor Code that was voted on at this July’s National Assembly session.

At the same time, he is gradually gaining experience representing the country abroad and building relationships with the island’s key allies. He has led delegations to China and Vietnam and makes periodic trips to Venezuela.

Many outside observers believed that Cuba’s socialist economy would collapse after Fidel Castro fell ill. Instead, there was a smooth transition to Raúl Castro. Now Raúl has apparently chosen Díaz-Canel to manage the post-Castro transition.

But it will be no easy task. There could be power struggles to replace him at the top. He also faces a difficult balancing act of meeting the expectations of those who want to see faster and more profound changes, and those within the party who have a vested interest in the status quo. Without the authority that goes with being one of the original revolutionaries, Díaz-Canel will need all of his political and management skills if he is to lead Cuba into the post-Castro era.

By Richard E. Feinberg and Colin Laverty

Pomp and circumstance: Yamina Vicente prepares for a graduation ceremony at the Habana Libre Hotel. Photo: Ernesto J. Fernández.

Yamina Vicente was marked early for a leadership position in the public sector. After studying at the elite Vladimir Ilich Lenin Preparatory School in Havana, she earned her master’s degree in economics from the University of Havana, graduating at the top of her class. A rising star, Vicente was honored with teaching posts, sent to Venezuela to give lectures, and awarded prestigious positions in the state-run Grupo Azcuba at the heart of Cuba’s sugar economy.

But with two small children, Vicente, 31, found that she simply could not make ends meet on her meager state salaries. She had always dreamed of having her own business, despite the culture at the university that degraded working in the for-profit sector. But she had no entrepreneurial experience and was unsure about what field to enter.

So when the government released its expanded list of authorized private-sector businesses in 2010, Vicente and her sister Maurisel pored over the opportunities, looking for something that did not require much up-front capital and that might fit their skills and interests. “We studied the list of permissible activities trying to find the one that we found most interesting and the most modest investment,” she recalls. “We settled on party planning.”

In 2013, the sisters launched Decorazón, a family firm offering decorations and event coordination for social events. With her talent for design and manual arts, her high energy and contagious optimism, it seemed a natural fit.

The sisters raised $600 in small loans from family and friends on the island—not accessing remittances, as do many aspiring cuentapropistas (small business owners)—to purchase essential inputs: colored cloth, artificial flowers and pedestals, and air compressors to blow up balloons. Working out of their homes in Havana, they initially offered their event-planning services for weddings, birthdays and quinceañeras. But they have slowly expanded into more complex events, such as business celebrations in private restaurants and baptisms. In addition, some new traditions are taking hold in Cuba, such as Halloween parties and baby showers, for which Decorazón has quickly started to offer services. Unlike many of the new private firms that cater to tourists and expats, 85 percent of Decorazón’s clients are Cubans.

The growing business now organizes about eight events a month, yielding revenues of roughly $1,000 a month, out of which the sisters religiously reinvest 10 percent to upgrade and expand their products. While they continue to put together the routine living room or backyard birthday parties, Yamina and Maurisel can often be found calling the shots at elaborate weddings at Cuba’s finest hotels. To help organize and staff their events, Decorazón has built a network of more than a dozen other cuentapropistas that enables them to offer a complete package of photography, videography, makeup, and other services. Current tax and labor laws, which impose financial and bureaucratic burdens on direct hires, make such informal contracting more practical for entrepreneurs, Vicente says.

In May 2014, Vicente completed her course of studies at Proyecto Cuba Emprende, a project of the Catholic Church that offers training and advisory services to Cuban entrepreneurs. With a focus on human resources, accounting, marketing, and sales, Cuba Emprende’s curriculum enabled her to better organize Decorazón. Vicente is also thankful for changes in U.S. policy that have granted some Cubans a multiple-entry, five-year visa to visit the United States. “I’ve now visited the U.S. on several occasions, not only Miami, but Washington DC, and other cities, and each time I come away with new ideas and motivations,” she says.

Decorazón is very sensitive to market conditions. Products and prices are tailored to the interests and financial capabilities of clients. But Vicente is also very conscious of quality, and she and her sister meet with each prospective client. “As a family firm, Decorazón offers personalized services with a very warm, human touch,” she proudly asserts—and her personal dynamism and bright smile would make it hard for any client to resist her sales pitch.

Decorazón’s future expansion, however, depends on the ability to find a reliable source of materials for her events. Vicente is frustrated by trade restrictions imposed by both governments that prevent her from directly importing the many marvelous party supplies she has come across in her visits to the United States. Another constraint: Internet access remains expensive and inconvenient, making it difficult for her to exploit her ideas for publicity and marketing.

Nevertheless, Vicente brims with enthusiasm about the future. Already, her university days and public-sector career seem light years away. The maturing entrepreneur hopes to open subsidiary offices in provinces outside of Havana and to offer services and gift items online. Her current state of mind: “Business is my means of personal and professional self-realization. I grasp that there are no limits but my own efforts.”

By Fernando Sáez and Inés Aslan

Privately busting a move: MalPaso Dance Company practices in Havana’s El Vedado neighborhood. Photo: Ernesto J. Fernández.

The changing economic and political climate in Cuba has injected new entrepreneurial energy into the country’s cultural life. One example is the Havana-based MalPaso Dance Company, created in 2012 by Osnel Delgado and Daile Carrazana—two former members of the modern dance company Danza Contemporánea de Cuba—together with Fernando Sáez, the director of performing arts programs at the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba (LFC).

Cuba’s 2011 economic reforms that granted more space for private business allowed Delgado and Carranza to develop independent projects outside the government-run dance troupes. With Delgado’s talents as resident choreographer and Saez’s managerial experience, MalPaso Dance Company developed a creative vision combining the island’s strong Afro-Cuban dance and musical tradition with the abstract and theatrical movement prevalent in American and European modern dance.

The MalPaso Dance Company’s goal is to not only train emerging Cuban choreographers to develop and showcase their work, but to establish a relationship with the U.S. modern dance community. The connection isn’t new; Cuban modern dance has long drawn from contemporary American dance traditions. The group includes 13 members and receives support from the LFC as well as from its sister organization, American Friends of the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba.

MalPaso Dance Company’s first steps outside Cuba came in May 2014, when the company debuted at the Joyce Theater in New York. The performance featured two works: 24 Hours and Dog by Delgado with original live music by prominent American composer and musician Arturo O’Farrill; and Why You Follow by American choreographer Ron K. Brown. That was followed by a run at the Light Box in Miami. The company will return to the Joyce Theater next March and is expected to perform at the renowned Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Massachusetts.

And while MalPaso literally translates to “wrong step,” the company’s success is anything but; both performances in New York and Miami were sold out and well-received by critics. With the strong support of American cultural organizations such as the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Joyce, Cuban independent artists—cultural entrepreneurs, if you will—like MalPaso are helping to increase collaboration and understanding across the Florida Straits.

By Margaret Crahan

University with a view: The main steps of the University of Havana overlook the city’s Centro Habana neighborhood. Photo: Ernesto J. Fernández.

Change is permeating Cuban society, and nowhere is this more evident than in the economy. One of the contributors to that change is the Faculty of Economics at the University of Havana. The school in Cuba’s premier university has emerged as a catalyst for innovative socioeconomic policies and programs since the Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba introduced, in 2011, a series of changes or, literally, guidelines—los lineamientos—aimed at making the Cuban economy more productive and efficient.

Underlining its critical role, more than half of the school’s 90 professors are members of committees or commissions charged with proposing strategies for, and evaluating the implementation of, the government’s lineamientos.

Several professors, for example, served as non-permanent members of the Commission on the Implementation of the Conceptualization of the Economic Model. Other professors worked on new pricing policies, acted as consultants on plans to eliminate the dual currency system, and served as advisors to the Commission on Cattle and Crop Raising. Others have been involved in analyzing all aspects of the Cuban economy—focusing on projects such as developing methodologies for evaluating investment, financing enterprises, devising alternative forms of management of state-owned enterprises, and diagnosing their economic and financial problems.

Moreover, the Faculty of Economics leads the coordination of the Permanent Commission of Economic Sciences, tasked with developing and analyzing studies and proposals related to the implementation of the revised Cuban economic model.

Their work has not only deepened the quality of economic analysis both within and outside the university, but also provided opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students, as well as professors, to test theories and models in a practical fashion. In the past five years, the research informed 220 senior theses, 99 master’s essays and six dissertations, training the next generation of economists. It also resulted in 385 articles and 18 books, 34 of which have earned international or national prizes, including from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America.

Before 1962, economics did not exist as a specialization at the University of Havana. Today, there are over 1,000 undergraduate and graduate students, as well as more than 1,200 participants in educational outreach programs for government officials and managers of state enterprises. Approximately one-third of the faculty also offers courses in public administration for government bureaucrats.

And the impact on Cuba’s economic leadership structure has been substantial. Over the past five years, 35 master’s or doctoral graduates have been employed by the Cuban banking system, including the Central Bank; over 100 have been incorporated into various ministries or their branches; and others have worked with multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, Organization of American States, and the CAF development bank.

Among the younger professors is Yordanka Cribeiro, who is currently head of the Department of Macroeconomics. Her field is human capital, and she has studied the declining role of skilled labor on Cuban economic growth. Another, Yaima Doimeadios, received her doctorate from the University of Havana and is currently an assistant dean of the Faculty of Economics. She specializes in macroeconomics and has studied efficiency in public spending. Yaimary Marrero received her master’s in business administration from the University of Havana and specializes in operations and the logic and techniques of negotiations. She has studied at the Universities of Córdoba, Cádiz, Dresden and Humboldt and is currently a vice dean at the Faculty of Economics. Alberto Menéndez has a master’s in economics from the University of Havana. His fields include methodology, planning and price setting, and he is currently studying for his doctorate and is a visiting scholar at the University of São Paulo.

These professors represent the next generation of experts who will help inform and shape Cuba’s economy.

What motivates some of Cuba’s best and brightest to study economics? One student recalled that although he was initially attracted by the prospect of career and professional options, he soon discovered the importance of economics to all aspects of a society—particularly in the way individuals relate to one another. The study of economics, the student concluded, offered a perspective on history that enabled him to understand his responsibility for helping create the prosperous future Cuba deserves.

By Maria Hinojosa

Yoani Sánchez smiles during a news conference that was part of her 80-day tour of South America, Europe and the U.S. in 2013. Photo: UESLEI MARCELINO/REUTERS.

Maybe because so much of the old revolutionary Cuba seemed larger than life, it’s ironic that one of the government’s most formidable critics is a petite woman in her late 30s. Yoani Sánchez is a wife, mother and writer. She is also a modern-day freedom fighter who, rather than taking up weapons, writes eloquently about her daily life.

Her public account of that life constitutes a perpetual barrage of “truth bombs” lobbed at Cuba’s government. The immediacy, simplicity and honesty of her personal blogs have resonated throughout the world.

While she has plenty of reasons to worry about the consequences of what she says and writes, Sánchez appears entirely serene. The soft-spoken 39-year-old has become one of the most famous people to take on one of the most famous revolutions of our time.

Sánchez hasn’t challenged the government by protesting in the streets of Havana, which would surely land her in jail. She started her quiet protest by writing about her daily life. To publish her writing, she did what was once completely unthinkable: she started a blog in Cuba. Unthinkable, because Internet access—and all of the education that comes with it—is incredibly limited on the Island.

Sánchez is a writer. But like most Cubans, she is also a fixer. To get through life, ordinary Cubans find they must learn to become fixers of broken can openers, worn-out shoes, or a car engine that has broken and for which no spare parts exist. So as a kid, Sánchez learned how to build things. And as a teenager, she once built her own computer.

She has thousands of Twitter followers, even though, for her, Twitter is a one-way street. She posts by sending text messages to friends off the island. But she can never read what people write back and can never respond. Her blog, Generación Y, is read by thousands, and in the past few months, Sánchez launched a digital newspaper, 14ymedio.

Born in 1975 in a tenement in Havana, Sánchez finished high school during the Special Period in the 1990s when scarcity was the norm. She had dreams of becoming a journalist but instead wrote her thesis on philology, titled Words Under Pressure: A Study of the Literature of Dictatorship in Latin America. In 2002, Sánchez left for Switzerland but two years later returned, committed to staying in her country to bring about change.

“Labeling is the core of Castro’s Cuba,” says Sánchez . “It is the official way of dividing the country. You label some people with glorious epithets and others with dismissive ones. Then the government accuses you of being unpatriotic and they try to take away your own right to nationalism, and try to push you into exile.”

But while the government may try to wish her away, Sánchez, like other Cubans who have challenged the regime, contends she is demonstrating her patriotism by staying.

Through her blog, many people beyond the island have become aware of the challenges facing many Cubans in their everyday lives, such as finding enough to eat or making ends meet on state salaries of $20 to $30 a month. Many have left their professions in the state sector in favor of more lucrative opportunities that cater to the growing tourism industry and are paid in dollars.

Sánchez remembers growing up with the slogans and promises of the revolution. As an adult, she began to ask herself: what happened to the Cuba she had been promised?

“No one would give me a microphone or a newspaper column or a minute on TV to ask that question,” she says. So she combined her flair for writing and her frustrations over daily life on the island, together with her love of “technology and cables, screens, the feel and texture of the keyboard,” to create her blog and newspaper.

But Sánchez also represents more than traditional political dissent. Technology offers a passport to the outside world that was unavailable to Cubans for the majority of the past 50 years. In fact, young people like Sánchez’ 19-year-old son have reached a point where they aren’t as concerned about what the government does or says anymore.

“They have developed selective hearing,” Sánchez says in awe. “Their focus is on the outside and being a part of the greater world that is connecting through technology. They have managed to leave behind a past, the Castro past, that my generation is still dragging along.”

It’s a lesson that governments are learning in many other troubled parts of the world—from Asia to the Middle East. In Cuba, one determined and soft-spoken women has demonstrated that even a homemade instrument of simple cables, screens and a keyboard is the twenty-first century’s most powerful driver of truth and understanding.