If you were a Mexican attorney general allegedly hiding your Ferrari from tax authorities, a former Brazilian minister trying to squirrel away $16 million in ill-gotten cash, or a Uruguayan vice president accused of using official funds to buy jewelry – well, you just had a very bad week.

All of them got caught, in one way or another. This was shocking, but not in the way you might expect. Indeed, it has become abundantly clear since 2014, when the “Car Wash” investigation first erupted in Brazil, that corruption in Latin America is much more likely to be detected and punished than ever before. Rather, what’s truly surprising is that so many of the region’s political and business elites continue to behave as if they didn’t get the memo.

Whether this is because old habits die hard, or the absence of meaningful reform, or pure pig-headed greed, is open to debate. But the stubborn persistence of the old practices is already having repercussions far beyond the swelling ranks of tycoons, former presidents and ministers who can be found in the jail cells of Brasília, Lima and Guatemala City. Anger over corruption has taken hold as the region’s number-one public issue at a time when, over the next year, nearly two-thirds of Latin Americans will elect a new president. The establishment’s collective failure to read the writing on the wall is pushing electorates toward outsiders who promise to tear down the whole system – the good and the bad. The worst potential outcome is not a Donald Trump – it’s a Rodrigo Duterte. In some countries, notably Brazil, it’s no exaggeration to say that democracy itself is at risk.

It didn’t have to be this way.

Latin America’s anti-corruption wave has been rightly celebrated as a watershed – another step forward for a region where democracy and capitalism have largely flourished over the last 30 years. As amply chronicled here in Americas Quarterly and elsewhere, the root causes behind the trend include the rise of independent national judiciaries, the power of social media and smartphones to shine light where previously there was none, and a middle class that has grown by 50 million people in recent years, and is now less concerned about hand-to-mouth issues and more focused on good governance. From Mexico to Colombia to Argentina, the hunger for greater rule of law and accountability is unmistakable, even if the pace of change varies widely.

Virtually every Latin American leader has at least given lip service to the need for change. But many actions have been incomplete at best – and counterproductive at worst. For example, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto said in 2014 he would support a new “anti-corruption system,” following an embarrassing conflict-of-interest scandal involving his wife. The announcement initially won praise. Since then, Mexican anti-corruption activists complain they have been harassed and spied upon, while the “system” itself remains stuck in bureaucratic limbo. Peña’s other big move – the creation of a new, more independent attorney general’s office – suffered a grave credibility blow last week when the nominee for the post was revealed to have registered his $220,000 Ferrari to a house worth just $25,000 on the outskirts of Mexico City – a classic tax dodge. The official’s lawyer said this was an “administrative error,” and would be corrected right away.

Laugh if you want – I’ll admit, I did – but these stories just never seem to stop. In some cases, leaders have openly schemed, as with Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales’ failed ploy to fire the same prosecutor who jailed his predecessor for corruption in 2015, and may now be closing in on him. But in other instances, such as one that led to the imprisonment on Sunday of Brazilian beef tycoon Joesley Batista, or the credit-card scandal that caused Uruguay’s vice president to resign on Saturday, it seems the accused simply failed to grasp that the world has changed – that “Car Wash,” “La Linea,” “La Casa Blanca” and other recent scandals weren’t some kind of exception or passing fad. It makes you want to grab them by the shoulders: Don’t you know you can’t do this anymore without getting caught?

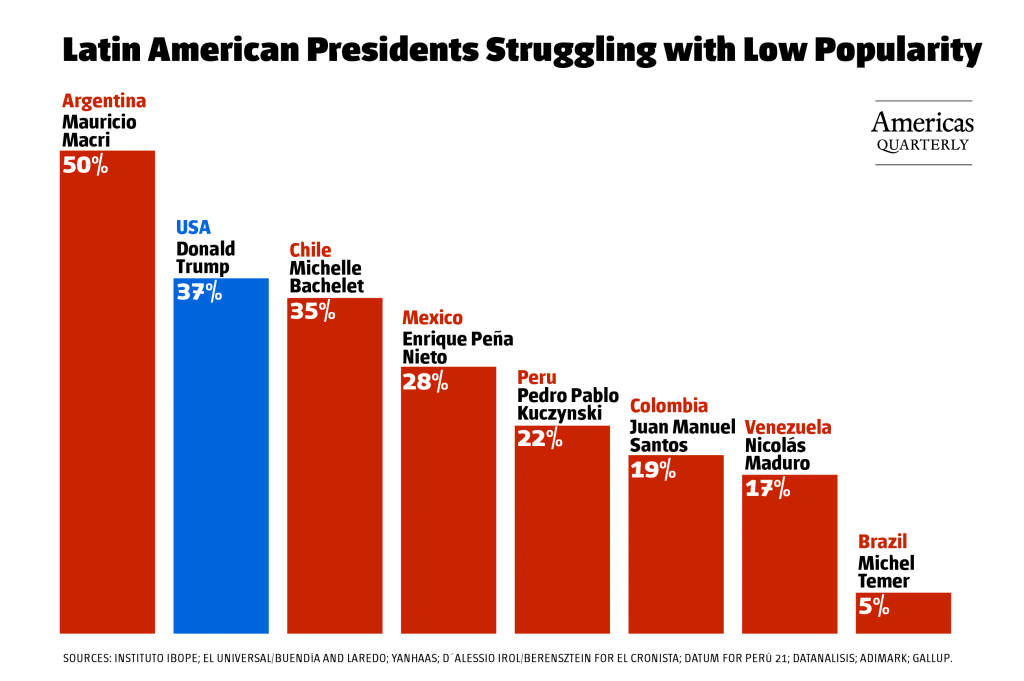

Few seem to fully grasp the depth of the public’s anger, either. I have spent 2017 traveling to Latin American capitals – Santiago, Brasília, Mexico City, Lima, and so on – and fielding endless variations of the same question: When will Trump’s government fall? How can he possibly survive, given his abysmal approval ratings and constant scandals? That’s fair to ask, but it risks obscuring a similar phenomenon closer to home. If you take the presidents of Latin America’s seven most-populous countries, only one of them has a domestic approval rating higher than Trump’s. (See chart below.) Circumstances vary, but public fury over scandals is a significant factor – or the main factor – behind their low popularity, which has in turn stymied efforts at economic reform and left several countries feeling adrift.

Sensing opportunity, candidates in upcoming presidential elections in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Chile have seized upon corruption as their casus belli. In some cases, this is promising: Sergio Fajardo, a former mayor of Medellín, is a moderate who has spoken convincingly and often of the need for greater transparency. Others, such as Mexican leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, may end up using corruption as an excuse to rewrite the rules for vast sectors of the economy. Jair Bolsonaro, a former Brazilian army captain who has ridden an anti-establishment, law-and-order message to first or second place in most polls, expresses nostalgia for the 1964-85 military dictatorship and says he would give police “carte blanche” to kill suspected criminals. It would be a shame if revulsion over graft pushed countries into authoritarian arms. But it’s certainly happened in Latin America before.

So where is all this headed?

I have wondered lately if the true historical analogy is not The Untouchables, the Hollywood movie about busting Chicago’s mafias in the 1930s that Car Wash judge Sérgio Moro has cited as an inspiration. In darker moments, I fear a better (if still imperfect) comparison may be the Arab Spring: in which a region rebelled en masse against the status quo, initially generating great hope and admiration around the world, but ultimately proved unable to install something better – and, in some cases, ended up with something worse.

Rather than get all fatalistic about it, though, there are better paths forward. The region’s private and public sectors must have a frank dialogue about how to reform the current rules of engagement, and reduce opportunities for corruption. Civil society should continue to beat the drum for cleaner government, while supporting candidates who will embrace it within the norms of liberal democracy. Finally, there’s still time for some current politicians to adjust – and reap the benefits. It’s no accident that, in the chart above, the lone exception to the region’s low approval ratings is Mauricio Macri of Argentina. While not perfect, he has followed a government plagued by endemic graft with credible attempts at greater transparency and reform – which has bolstered his popularity, even at a moment of economic uncertainty. In that sense, Macri may be Latin America’s first successful post-Car Wash president. May there be many others.