As a trial judge, I have heard hundreds of cases involving charges of false arrest and excessive force by the police. All of these cases turn on credibility. The victim (assuming he or she is alive) tells the story from his or her perspective, and the police officers (often more than two) tell their story. The jury is left in the difficult and uncomfortable position of deciding which side is telling the truth and which side is providing false testimony.

One example makes the point. In a criminal case in Chicago, five police officers swore under oath that they pulled a suspect over after he failed to use a turn signal. One officer testified that when he asked the driver to produce his license and registration, he smelled marijuana and directed the suspect to leave the car and stand by the trunk as the vehicle was searched. During the search, officers found nearly a pound of marijuana in a backpack on the back seat of the car. Based on the discovery of the marijuana, the driver was arrested.

The suspect testified to a starkly different version of events. He swore that he used his turn signal, was never asked for his license and registration, and that the marijuana was not in a backpack on the back seat of the car, but was hidden under the seat. Then the suspect’s lawyer got lucky. At the last minute, he subpoenaed and obtained a video that had been recorded automatically by the police car—which the police witnesses must have forgotten about. The video showed that immediately after being stopped, the suspect was removed from his car, frisked and handcuffed. The search of the car occurred after the arrest.

The judge found that all five officers had lied and engaged in “outrageous conduct.” She called it a conspiracy to lie, and suppressed both the arrest and the fruits of the search. Without that video, it would have been hard for a judge to find that five police officers had lied under oath while a guy caught with a pound of marijuana had told the truth.

But that is exactly what happened.

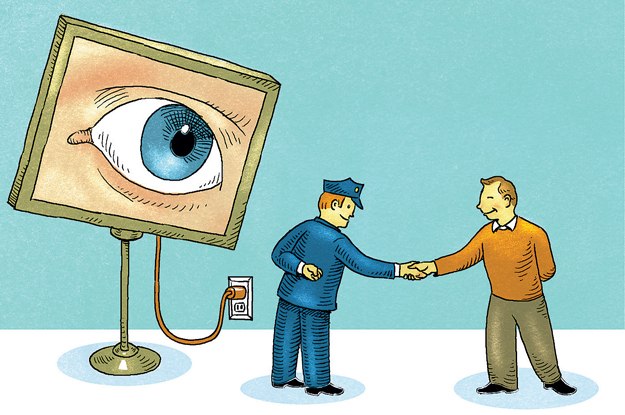

The point should be clear: people behave differently when they know they are being watched, and police are no exception. Officers wearing body cameras will be less aggressive and more respectful when they interact with members of the community. They will also be more reluctant to use force unless it is necessary to protect themselves and the public. While body-worn police cameras may not be a panacea, they will not only lead to a reduction in the use of unnecessary or excessive force by police officers, but will also be beneficial for both the police and the community.

Evidence supporting this belief comes from jurisdictions in which experiments with the use of body-worn cameras have produced encouraging data. In one such jurisdiction—Rialto, California—after the police force had worn body cameras for a full year, citizen complaints against police declined by 60 percent. Other jurisdictions that have implemented body cameras have seen similar results. In Mesa, Arizona, for example, use-of-force complaints decreased by 75 percent for officers using cameras in a pilot program.1 In Nampa, Idaho, they dropped by 24 percent.2

Another important statistic from the Rialto study is the number of incidents that resulted in the use of force by an officer, which dropped by 88 percent after the use of body cameras. Officers who were not equipped with cameras were twice as likely to use force as officers who were. Even more tellingly, when officers wore cameras, every incident of physical contact was initiated by a member of the public, but in the absence of cameras, 29 percent of the incidents involving physical force were initiated by the officer.3

Such studies have taken on increased significance in the wake of controversy over the deaths of several African Americans at the hands of police over the past year. This includes Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager who was shot by an officer in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, who died after being placed in a chokehold by a police officer. President Barack Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder have called for greater use of body-worn cameras by police officers. But even before these incidents, I concluded that such cameras could play a role in curtailing abuses of the long-standing police practice in New York of stopping and frisking young men—most of them African American—on suspicion of criminal behavior. As part of my August 2013 ruling in Floyd v. City of New York that the disproportional use of stop and frisk constituted a pattern of racial profiling and violated the U.S. Constitution, I ordered the New York City Police Department to conduct a trial in selected precincts requiring officers to wear body cameras.

The use of body cameras will also protect police officers. No longer will a person be able to claim that a police officer punched or kicked him without cause, when in fact it was that person who initiated the encounter by threatening or attacking the police officer. The contemporaneous record of what occurred should make it clear whether the officer was justified in using force. Everyone has a right to act in self defense. A video presents an unbiased account of the events. It has no motive to lie and no stake in the outcome. It merely records the event as it happens. If a police officer acts lawfully, then he should not be wrongly accused, forced to defend himself and risk a punishment he does not deserve. The camera will provide his defense.

There are some drawbacks to the use of body cameras—such as privacy concerns for both officers and the citizens they encounter, the storage of data capturing images of innocent people, the possible tampering with the images, and the accuracy of the images (with issues relating to lighting, lens clarity, movement, and angles). However, there is far more benefit than harm associated with their use. Once people know their actions are being recorded, their behavior changes. I am confident the widespread use of body cameras will reduce the amount of excessive force by police officers and will improve their relationships with the citizens they encounter and protect.

Given existing technologies, we should have the best evidence available at our fingertips. And speaking of fingers, millions of fingerprints are kept on file in case the police need to identify a suspect. Today, DNA databases are also available to law enforcement. Everyone agrees that DNA should be collected so long as storage and access are both carefully regulated. There is no reason that contemporaneous recordings of police encounters should not be treated the same way.

Read Peter K. Manning’s argument here.