The rules of the game of chicken are simple, and its stakes are high: two cars accelerate toward each other, and the first one to swerve loses. Do nothing, and both players end up in a fiery collision that threatens bystanders. Brazil’s executive and legislative are playing this game, without a failsafe. Brazilians could be the ones who suffer if the game ends in disaster.

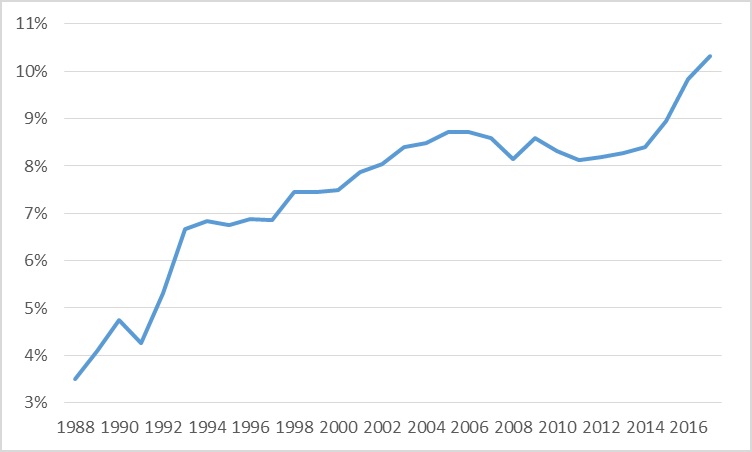

Many countries face looming crises in this sector, but Brazil’s situation is unique: its combination of a rapidly aging population, extremely generous pensions and a low minimum retirement age is unmatched in middle-income countries. Under the current pension system in Brazil, for example, the average retirement age of individuals who pay into the system is 55 years old; women who began to contribute as 15-year-olds can retire at 45. These lax rules are, in part, responsible for a public pension system that comprises more than 50 percent of all federal expenditures, once you discount transfers to the states, crowding out other public services, according to the authors’ calculation using government data. Its payouts are triple what they were thirty years ago (see the graph below) and are expected to accelerate further. We estimate that under current conditions, pension expenditures will rise more than 3 percent per year in real terms.

In the terms of the game of chicken, given current conditions, the crash is unavoidable.

Figure 1 – Federal government expenditures on public pension as percent of GDP.

Source: Authors’ estimates based on data from various government sources.

Source: Authors’ estimates based on data from various government sources.

This situation has been building for years. The last two reforms were under Presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso, in 1998, and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in 2003, but neither tackled the minimum age requirement. President Dilma Rousseff ignored the subject, and hired more public employees. In 2016, when President Michel Temer assumed the presidency in the wake of Rousseff’s impeachment, Brazil was mired in the deepest recession in modern history. The population was hurting; per capita GDP shrunk by 8 percent between 2015 and 2016, and the country faced a record public deficit.

Temer promised to pursue a business-friendly agenda. Reforming the pension system would be the capstone of his short tenure in office. He started by pursuing incremental reform to curb the rising deficit. His administration’s first significant piece of legislation was aimed at reforming the labor legislation. Later, came Lei do Teto (The Law of the Ceiling, meaning an expenditure ceiling). Under this hard budget cap, the federal government expenses cannot rise in real terms, after taking into account inflation, for the next 9 years, at least.

Temer’s strategy was clear. A hard budget cap would work as a commitment device to force pension reform through an unwillingly Congress and past the lobby of special interest groups, especially the powerful judiciary, which benefits the most from ridiculously generous pension promises. With the cap, there is no way out – Brazil either embraces reform or faces chaos.

And so, Brazil’s current game of chicken was set up. If nothing changes, we estimate that the federal budget for expenditures beyond payroll and Social Security payment would have to shrink by almost 20 percent (in real terms) through 2026. The math is simple: given that the budget cannot increase in real terms and that pensions, which already account for half of the budget, will increase by 3 percent a year, then other spending has to decline. Health and education are protected by the new cap rules but everything else would be fair game. Brazilian society will not accept this. Our conclusion: If nothing changes, the current budget structure would eventually collapse, likely by 2022.

This should be the moment to act. Indeed, Temer’s administration had worked out a plan with Congress that would revamp the private and public pension system by, among other measures, establishing a minimum retirement age of 65 for men, and 62 for women. Brazil’s economy is finally recovering from the deepest recession in modern history. During 2018, analysts expect the Brazilian economy to grow 2.8 percent, and inflation to be around its target, at 3.8 percent. Failure to pass pension reform could impact this, creating uncertainty and making any sustained recovery over the next few years much harder.

The only other option, getting rid of the hard cap, can postpone the collapse but doing so will result in either a deep recession or a spike in inflation. After all, expectations matter to macroeconomic outcomes. Backtracking on the newly-minted cap rule will make real interest rates increase and investments shrink. Brazil has already one of the highest interest rates in the world, with lending rates up to 50 percent; aggregate investments are relatively small in relation to GDP, at around 15 percent. Either the Central Bank will respond by trying to force interest rates down, accelerating inflation, or it will sit passively and watch another bout of recession and unemployment, currently at around 12 percent.

And yet, here we are, dancing on the edge. After taking a step in the right direction for the economy, President Temer’s government lost its drive, diverted by many scandals. Survival cost him much of his political capital, leaving very little for pension reform.

So, what are the potential outcomes of Brazil’s current quandary? This is the best scenario: a pension reform plan sails through Congress and the Senate and the economy continues to recover. Whoever wins the presidential election in 2019 continues to reform the Brazilian economic system, tackling the cumbersome tax code, opening the economy (it has the lowest ratio of export and import to GDP in the world), cutting red tape that makes Brazil one of the most challenging places to do business, and more.

Recently, the federal government decided for a military intervention in the state of Rio de Janeiro, which has been experiencing a surge in violence and where 1 percent of all murders in the world take place. This prevents the constitutional change that would be necessary for pension reform. Elections are in October, and the current lame duck president can at best pass a half-decent reform before stumbling to the finish line. Meanwhile, Brazil’s debt has been downgraded further into junk territory.

Given that scenario in Brazil’s current game of chicken, what will happen as that 18-wheeler loaded with burgeoning public pension costs continues to pick up speed, with no reform in sight? The government – that is, the millions of Brazilians who depend on it – will suffer.

The conclusion is unmistakable: pension reform is essential, particularly under Brazil’s hard budget cap. But all is well that ends well, the saying goes. Much hope hangs on the October presidential elections. Hopefully, we don’t get turned into chicken soup.

—

Rodrigo Zeidan is a business and finance professor at New York University in Shanghai and Fundação Dom Cabral.

Fabio Giambiagi, chief economist at Brazil’s National Development Bank (BNDES), is also a columnist and author of 25 books about Brazil’s economy, including four about the pension system.