Lea una versión en español aquí.

“Why do they hate us?” This question1, on so many U.S. citizens’ minds over the decade following the September 11, 2001, attacks, is often asked about Islamic extremists and even the broader Muslim world. Among the most common responses is that “they” resent U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East. When the focus shifts to Latin America, U.S. foreign policy similarly appears to be the principal reason for anti-Americanism. This seems to make sense. One would be hard-pressed to find another world region with greater and more long-standing grievances about Washington’s actions. The Monroe Doctrine, Dollar Diplomacy and Cold War Containment were euphemisms for imperial abuses committed against Latin America over the course of two centuries.

However, as we show here, Latin American citizens today are not overwhelmingly anti-American. In fact, polling data suggest that on balance the opposite is true. Clear majorities of respondents in nearly every Latin American country hold positive opinions of the United States. Even more surprising, many of the countries where U.S. intervention has been most frequent and dramatic (e.g., the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama) are also the countries where mass opinions about the U.S. are most favorable.

The fact is, the question at the start of this article should be turned on its head: “Why don’t Latin Americans hate us?”

What accounts for these puzzling findings? Economic self-interest offers one clue.

The polling data indicate that the stronger the economic ties between a Latin American country and the U.S.—whether related to trade, aid, migration, remittances, or investment—the more favorable are its citizens’ opinions toward the “Colossus of the North.” This explains why Caribbean and Central American countries, despite being more historically victimized, are the most pro-American. Put another way, Latin Americans like the U.S. because of their stronger economic ties, relative to the rest of the world, with their northern neighbor.

Assuming Anti-Americanism …

You would not know this from the rhetoric favored by some of the region’s intellectuals and political leaders. Historical events ranging from the annexation of half of Mexico’s territory (1848) to the deposition of democratically elected leaders (Guatemala in 1954) have, according to some Latin American elites and various scholars, built up a deep resentment in the region toward the United States. Leaders of Latin America’s new Left have followed closely in their footsteps. Among his many colorful statements, the late Hugo Chávez noted that “in all history, there was never a government more terrorist than that of the U.S. empire.”2 When Nicaragua and 32 other countries created the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in 2011, Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega boasted that the group’s creation amounted to “sentencing the Monroe Doctrine to death.”3

Many scholars believe anti-Americanism is deep-seated among ordinary Latin Americans as well. “Latin Americans are disparate peoples, but there are few things that unite them more than their shared resentment at the persistent record of U.S. high-handedness in the region as a whole,”4 according to George Yúdice. Another prominent thinker, Alan McPherson, believes that the more significant and frequent the U.S. intervention, “the more widespread, deep and visceral anti-U.S. sentiment became.”5 This resentment continues today, McPherson added, because “a generational sedimentation of grievances shaped historical memories and national mythologies.”6 Julia Swieg sees an “instinctive anti-American reflex”7 in the region, and Michael Radu describes anti-Americanism as a “deeply rooted disposition.”8

Overall, the story is simple and compelling: Latin Americans do hate us, and this resentment is richly deserved. The problem, however, is that this story is categorically untrue.

… but Observing Pro-Americanism

Even a cursory glance at public opinion data shows the alleged “shared resentment” to be non-existent—certainly since the 1990s. According to data from the 18-country Latinobarómetro survey series, the average Latin American held a positive opinion of the U.S. in every year between 1995 and 2010.9 In all 18 countries, respondents holding favorable views of the U.S. outnumbered those expressing negative views over this decade and a half. Typically, the former outnumbered the latter by a large margin. Figure 1 depicts these straightforward results.

[popupImage:/sites/default/files/images/Baker%20Figure%201.jpg popupTitle:Baker Figure 1]View an expanded version of the figure.[/popupImage]

Source: Latinobarómetro Survey, 1995-2010

More than 75 percent of those surveyed expressed favorable opinions of the U.S. in 10 of the 18 countries, and in no country did negatively inclined respondents outnumber positively inclined ones. The average percentage of Latin American respondents who expressed favorable opinions toward the U.S. (77 percent) was the same as the percentage who expressed favorable opinions toward China (77 percent), less than the percentage of respondents who expressed favorable opinions toward the EU and Japan (87 and 86 percent, respectively), and more than the percentage who expressed favorable opinions toward Cuba and Venezuela (55 and 51 percent, respectively).

A point of comparison is the average degree of anti-Americanism in the “rest of the world,” based on a sample of 45 other countries gathered through the Pew Global Attitudes project between 2002 and 2010. The average attitude in the rest of the world is more unfavorable to the U.S. than the most anti-American country in Latin America: Argentina.

In short, Latin Americans are pro-American and, in most countries, overwhelmingly so.

A closer look at these results reveals a pattern that is even more surprising, and even more damning, of the aforementioned assumptions about anti-Americanism in the region. The countries that are the most pro-American are all Caribbean or Central American nations.

These are precisely those countries that have been the most victimized historically by the United States. The vast majority of U.S. interventions have occurred in the countries to its near south, while imperial interventions have been a somewhat rarer occurrence in South America.

The military occupations during the Banana Wars, the violent containment measures of the Cold War, and even the few visible post-1989 interventions mostly—though not exclusively—occurred in the Latin American nations of the northern hemisphere. (Recall, as another example, the Roosevelt Corollary’s goal of turning the Caribbean into an “American lake.”)

All told, the findings leave us with two puzzles. First, why do Latin Americans like the U.S., despite Washington’s persistent pattern of violating Latin American sovereignty over the past 200 years? Second, why are the most historically victimized countries today the most pro-American?

It’s the Economy, Stupid

Answering the question requires looking a little more closely at Latin American attitudes and behavior. U.S. interventions, especially during the Cold War, were often welcomed by large segments of the societies in which they occurred (e.g., opponents of the Sandinistas or supporters of the Salvadoran military). After all, the U.S. almost always took sides in a pre-existing ideological and political struggle.

Memories are also short. Latin America is an overwhelmingly youthful region, and most people under 40 have no vivid memories or experiences of the U.S. actions that enraged their parents and grandparents.

We find that for most Latin Americans, the more immediate reality is that of international economic exchange with the United States. For Latin American countries, economic exchange with the U.S.—conceived in an inclusive sense as trade, investment, aid, migration, and remittance flows—coincides with positive thoughts toward El Norte. According to political scientists Joseph Nye and William Reed, strong bilateral economic ties between countries promote goodwill between partners by increasing tolerance, mutual trust, and cross-cultural understanding.10 Economic interdependence also creates a class of individuals that benefits materially from the ongoing exchange and has objective experiences to show for it. For example, in much of Central America, a large number of lower- and middle-class citizens receive remittances from friends and relatives working in the U.S.

Finally, the relative wealth of the U.S. associates it, in the minds of many Latin Americans, with material success and opportunity. Many Latin American consumers see U.S. brands—Calvin Klein, Hollywood, and even McDonald’s—as symbols of quality and sophistication, something that helps explain the prevalence of knockoffs like “Kalvin Clein” in informal markets.12

Consider these statistics, reported by the Inter-American Dialogue last year: “the U.S. currently buys about 40 percent of Latin America’s exports and an even higher percentage of its manufactured products. It remains the first or second commercial partner for nearly every country in the region. And it provides nearly 40 percent of foreign investment and upwards of 90 percent of the $60 billion or so in remittance income that goes to Latin America.”11 Being so physically close to the U.S., Latin America’s volumes of trade, migration, investment, and remittance flows with the northern colossus are greater than those of other countries, and their citizens are more positive toward the U.S.

Moreover, even within Latin America, it is those countries that are the closest to the U.S. that are the most pro-American. The reason why countries that were the most victimized—in Central America and the Caribbean—are the most pro-American is the greater economic interdependence they enjoy with the U.S. That’s borne out by the huge numbers of expatriates from those countries living in the U.S., and consequently more remittance flows—among other factors.

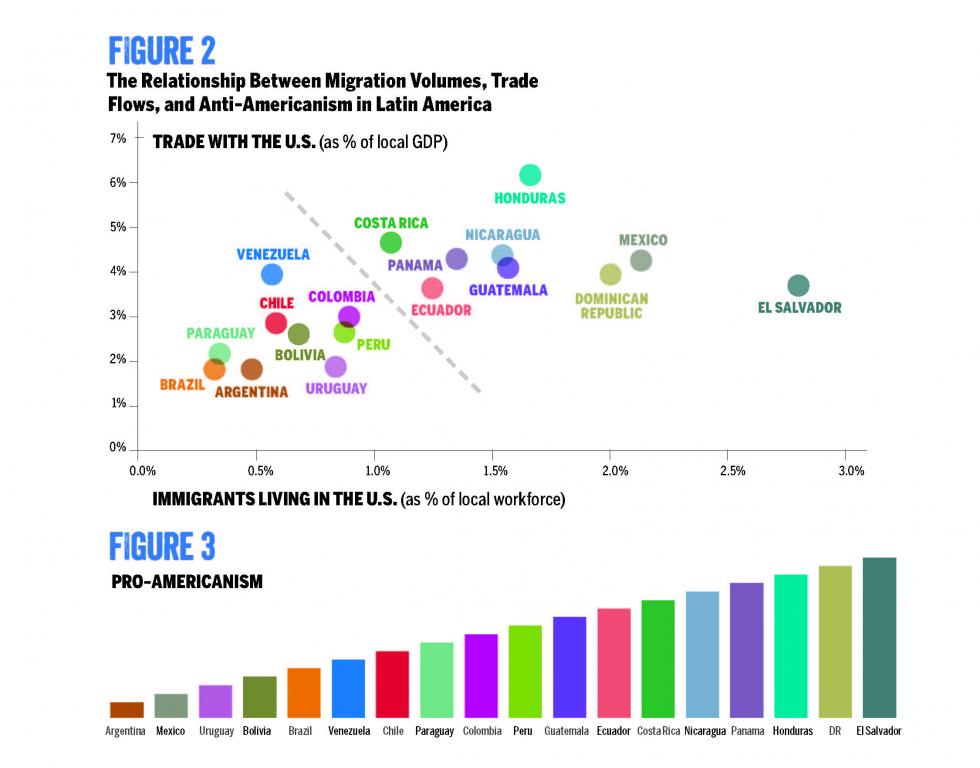

Although advances in technology and policy changes have dramatically lowered the costs of international exchange, physically proximate countries are still more likely to have higher degrees of economic interdependence than distant ones. Figure 2 shows this to be the case for inter-American economic relations. The scatterplot depicts 18 Latin American countries according to the number of emigrants they send to the U.S. (x-axis) and the amount of trading they do with the U.S. (y-axis).13 The diagonal line in the plot traces out a natural breakpoint that illustrates the impact of distance. To the left of the line are nine countries with relatively few emigrants to the U.S. and less trade with it, and they are all South American. To the right of the line are nine countries with a relatively large number of emigrants to the U.S. and a heavy volume of trade with it, and they are all Central American, North American or Caribbean (with the exception of Ecuador). In short, proximity to the U.S. correlates with a higher degree of bilateral trade and immigration.

View expanded version of the figure.

Source: Authors

Figure 3 traces out a third dimension providing evidence for the case that economic exchange with the U.S. creates massive goodwill even toward the region’s historical bully. Here is a representation of pro-American attitudes corresponding to countries in Figure 1. On the left side of the scale are countries with a relatively low percentage of pro-American citizens.

Again, the diagonal line provides a clear point of reference. Below it, in the South American countries where migrant and trade volumes to the U.S. are low, citizens are less favorable toward the United States. Above the line, in the Caribbean basin, favorability toward the northern colossus runs high.14 International economic exchange breeds goodwill.15

The one glaring outlier in the region is Mexico. The country is toward the upper-right corner of the scatterplot due to the well-known fact that Mexicans are tightly linked to the U.S. through their export markets, their relatives and friends who live there, and the remittances they receive back from them. Despite this, Mexicans are surpassed only by the Argentines in their lack of goodwill toward the United States.

Does this cast serious doubt on our claims? We think not. Of all the countries in the region, Mexico has surely been the most wronged by U.S. imperialism. It is the only one to have fought a major war against the U.S., the only one to have lost 50 percent of its land to the U.S., and currently the primary victim of U.S. demand for illegal narcotics. And yet Mexicans are, on balance, pro-American: 60 percent had a favorable opinion between 1995 and 2010. [See Figure 1.] If anything, international exchange between the U.S. and Mexico seems to be overcoming a goodwill deficit that otherwise would be much deeper.

Implications and Conclusions

The U.S. government has spent a lot of time and energy trying to shape how foreigners view America. George W. Bush appointed advertising executive Charlotte Beers as Undersecretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs in October 2001, just after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center—an effort in large part to counter the propaganda of jihadists. Beers, and later appointees Margaret D. Tutwiler and Karen Hughes, worked diligently to improve the U.S. brand. But they all left the post after a short period of largely failed efforts. Our findings suggest that at least in the Western Hemisphere, the energy involved in such activities could have been better spent elsewhere. The exchanges that take place between U.S. and Latin American economic actors are a much more effective means of promoting pro-American sentiment. Better yet, this channel of goodwill promotion is virtually free for the U.S. government, as it is driven by voluntary and daily incidences of what Adam Smith called the innate human “propensity to truck, barter and exchange.”

This does not mean, however, that the U.S. can simply sit back and assume it needs to do nothing at all. There are numerous policy opportunities for deepening and humanizing international economic relations in the region. Imports from the U.S. are a particularly effective mechanism of promoting the “U.S. brand.”16 Armed with that knowledge, a first place to start in reinforcing positive perceptions toward the U.S. would be re-launching the moribund efforts to form a Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA). The remaining countries in the region with which the U.S. does not have a free trade agreement (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela) are also, surely not coincidently, the ones that tend to have the least pro-American citizens.17 An FTAA for which the U.S. makes true concessions on agricultural protectionism could help to shift the calculations of countries that are genuinely holding out based on economic calculations.

Reform of U.S. immigration rules would also help. According to a report by the Inter-American Dialogue, “Washington’s failure to repair the United States’ broken immigration system is breeding resentment across the region, nowhere more so than in the principal points of origin and transit: Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.”18 To reiterate, we find little evidence of seething resentment in these countries, but we do agree that well-targeted immigration reform can only further goodwill toward the U.S.

Of course, foreign attitudes will not and should not be the principal worry of U.S. policymakers, but the beauty of these measures is that they are good not just for building mass goodwill but for the hemisphere’s economies as well.