The Captain of Industry | The Musician | The Entrepreneur

The Educator | The Oil Expert | The Politician | The Economist

The Humanitarian | The Rights Advocate | The Foreign Leader

This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro. | Leer en español

For years, Venezuela’s most famous musician wanted absolutely nothing to do with politics.

Even as the economy and democracy crumbled, Gustavo Dudamel remained quiet — focusing instead on his stewardship of El Sistema, Venezuela’s widely admired, state-financed music program, which over the past four decades has taught thousands of youths from all socioeconomic backgrounds how to play an instrument. In a deeply polarized country, the 37-year-old conductor and violinist preferred to use music as a tool to bring people together.

“El Sistema is far too important to subject to everyday political discourse and battles,” Dudamel wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2015. “It must remain above the fray.”

His stance enraged opposition leaders, who argued Dudamel, the music director of both the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, had a unique platform — and obligation — to call attention to the country’s plight.

Two years later, a bullet changed his mind.

As anti-government protests swept the country in mid-2017, numerous young musicians, including members of El Sistema, took to the streets to play their instruments as a symbol of defiance. Images of teenagers playing their violins amid clouds of tear gas and encroaching riot police swept the world. Then, in June, security forces shot and killed an 18-year-old viola player and El Sistema pupil named Armando Cañizales.

In response, Dudamel wrote a furious New York Times editorial condemning the violence and denouncing the government’s planned constituent assembly as unconstitutional. Creating a body that could rewrite the constitution and usurp sovereignty from the democratically elected National Assembly would only divide the country further, Dudamel wrote. “I am not looking to take sides,” he said. “I am willing to take a stand.”

The incident illustrated how Venezuela has deteriorated to the point that perhaps no one can remain above the fray. But it also showed the kind of leadership that cultural icons can provide in times of national turmoil. Dudamel may not be likely to ever run for office, or present a 10-point policy plan. But countries that successfully transition from authoritarian rule to democracy eventually go through a kind of national reckoning with their deep internal divisions — and that’s where Dudamel could be key.

In South Africa in the early 1990s, for example, musicians like Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela were known for their anti-apartheid activism, but they also played crucial roles after apartheid in helping heal a divided nation. “Musicians had the ability to create hopefulness,” said Stacey Vorster, an art historian at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Indeed, even in his critical op-ed, Dudamel tried to strike a note of inclusion — and to describe the kind of country a young father like him would want for his children. “This extreme confrontation and polarization is an obstacle to understanding and a peaceful democratic coexistence, and it cannot stand,” Dudamel wrote.

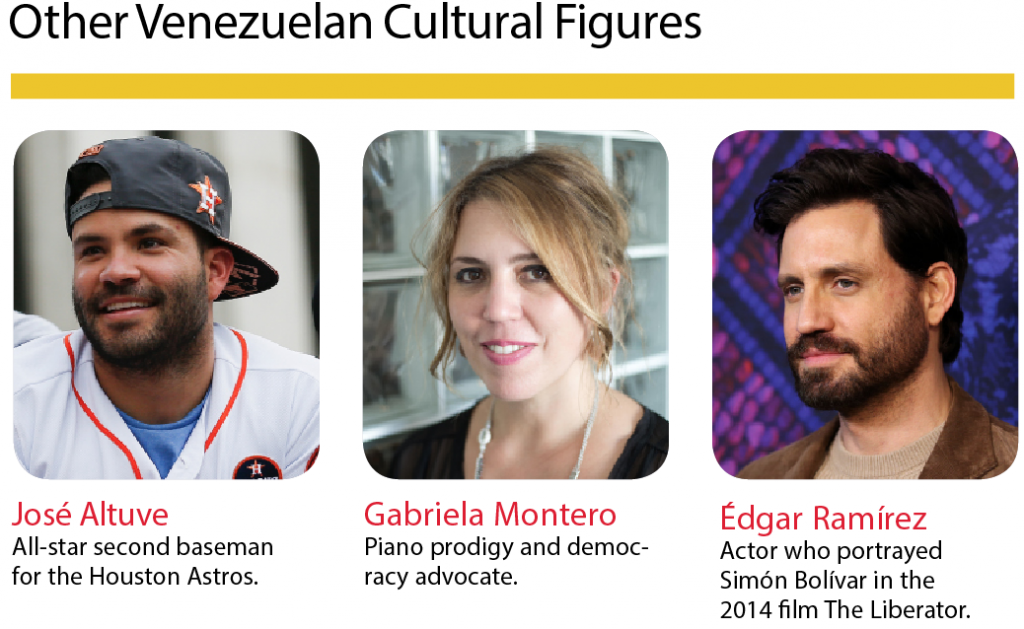

Other prominent Venezuelans, such as pianist Gabriela Montero, actor Édgar Ramírez and baseball player José Altuve, could also take up the mantle of national reconciliation. However, such figures have been either very vocal in criticizing the government, like Montero and Ramírez, or relatively quiet, like Altuve. Someone like Dudamel, who can speak to the most ardent opposition members without alienating chavista sympathizers, may be most effective at building bridges.

Through a representative, Dudamel declined to speak to AQ about whether he plans to remain vocal. But President Nicolás Maduro certainly seems aware of his importance — and determined to dissuade him from further interventions. Following his column, the government canceled Dudamel’s scheduled tours to the United States and Asia. “Welcome to politics, Dudamel,” Maduro sneered in a televised address.

There is much work to be done to restore what Venezuela has lost, but Dudamel and his young musicians seem up to the task. El Sistema’s motto, after all, is Tocar y Luchar: Play and Fight.