MEDELLÍN— For much of the 20th century, the Medellín River was an open sewer, collecting the untreated human and industrial waste of the Aburrá Valley.

Stretching through the valley’s center, Medellín — a fast-growing city with a reputation for entrepreneurship— turned its collective back and closed its collective nose. Warehouses and rail tracks buffered the city from the rank waters, fed by the hundreds of creeks that started out crystalline high above the city but collected raw sewage as they slalomed their way through the often informal neighborhoods that gradually expanded up into the hills.

“The river had very strong odors,” recalled Lucia Restrepo, 82, who has lived in the Conquistadores neighborhood near the river for the last three decades. “The water would be colored: one day red, and the next day blue.”

“Now it looks normal.”

She spoke as she strolled with her 29-year-old granddaughter, Verónica Bustamante, along a stretch of Parques del Río, an elegant riverside green space that, when completed, will straddle a short stretch of the river, with parks on either side connected by pedestrian bridges. With its boardwalk, art installation and methodically sown native vegetation, it is strikingly reminiscent of New York City’s High Line.

Lucia Restrepo said the water was once “red, then blue, but now looks normal.”

Lucia Restrepo said the water was once “red, then blue, but now looks normal.”

The park is routinely packed on weekends. But even on that weekday afternoon, families strolled, a couple wearing T-shirts of the popular soccer team Atlético Nacional smooched on a bench, and a half-dozen kites soared overhead. A stretch of the highway that once roared along the river now runs, invisibly and silently, through a tunnel underneath.

The construction of the park complex is one of several steps Medellín has taken to make it what many experts call Latin America’s most dramatic turnaround story in the conservation and management of water. While it’s true Medellín is relatively blessed with an annual 65 inches of rainfall, that’s no guarantee of success in this field; São Paulo, with 53 inches, had to resort to severe water rationing as recently as 2014. Plus, it’s true that water management is not just a question of water quantity, but also quality— and here, Medellín has truly become the envy of its peers.

The most recent milestone was the 2018 inauguration of Aguas Claras, a state-of-the-art, 1.6 trillion pesos (almost $500 million) water treatment plant that can process 6.5 cubic meters of water per second, 24 hours a day. Logs of sludge that result from the process go through a dehydration centrifuge and end up as biosolids, distributed to local farmers. The resulting output of biogas — largely methane and carbon dioxide — will eventually provide for a portion of the plant’s energy needs. All told, it and another plant now treat 84% percent of the valley’s wastewater, compared to less than 40% in Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole and an astonishing figure in a country where some cities treat next to none.

Not all is perfect; much of the river’s banks remain sandwiched in by parallel highways, and marred in several spots by trash. But the story of how Medellín got this far spans several decades and a wide variety of disciplines. It is not a story about money per se, but about careful management, effective community relationship-building, and an unusually comfortable mix of private- and public-sector values. Medellín has also earned praise over the years for transforming what was the world’s murder capital in the 1990s era of Pablo Escobar into a much safer city today; the 80% decline in its homicide rate is routinely studied in security policy circles. It turns out it’s something of a celebrity in the global water community as well.

“They are learning to take care of the resource, something they feel very proud about,” said Julián Cardona, water security coordinator for The Nature Conservancy for the northern Andes and southern Central America.

“Medellín is one of the most successful cases in the developing world.”

Medellín’s new treatment plant helps reuse wastewater and produces biogas.

Medellín’s new treatment plant helps reuse wastewater and produces biogas.

Public, but independent

The central character in any discussion of water here is Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM). Established in 1955 with the participation of local business leaders who believed dependable public utilities were crucial to the entrepreneurial city’s workforce, EPM is a venerated public entity with a presence in the city that is difficult to exaggerate. Its loopy EPM logo is ubiquitous, not just on workers’ uniforms but on office buildings, parks, libraries and even a spiffy Museum of Water; part of its profits is pumped back into city coffers; and it has a foundation that oversees extensive educational, cultural and community projects. Its subsidiaries work in other regions of Colombia, and extend into Central America and down to Chile.

According to Santiago Ochoa Posada, vice president of water and sanitation for EPM, the entity’s success is, in part, a result of being partially shielded from four-year mayoral election cycles. Though Medellín’s mayor is chairman of EPM’s board of directors, the company has historically operated with a considerable amount of autonomy. “Unlike what happens in the rest of Colombia and other Latin American countries,” Posada said, “this has permitted the company to make more long-term plans, beyond the single term of a mayor.” (Colombian mayors cannot serve two consecutive terms.)

It is, to be sure, far from perfect. Its project to build Colombia’s largest hydroelectric dam on the Cauca River, a project known as the Ituango Dam or Hidroituango, has fallen years behind and generated public outrage after a series of near-calamities. But EPM is still regarded with great reverence. Business leaders ranked it the most admired company in Colombia in 2015, 2016 and 2017; after Hidroituango it dipped to second in 2018.

“EPM is a very strong institution,” Sergio Fajardo, the city’s mayor from 2004 to 2007 and now a major figure in national politics, told AQ. “It’s an extraordinary example, a company that generates public wealth, wealth for the community, and has excellent relationships with the private sector, even though it’s a public entity.” Headquartered downtown in a hulking building with balconies bursting with greenery and its interior looking more like Google than government, the company is known for its generous benefits and professional development programs.

But as a public company it can focus less on maximizing profit, critical in a region where the experience of privatized water suppliers has been mixed. “For a long time — I’d say since the 1960s — this company has had a mission of bringing services to the whole city,” said Ochoa.

He does mean the whole city. Even more extraordinary than the 84% of wastewater EPM manages to treat is the 97% of homes that are connected to the official water system and the 95% to sewers — both figures are huge outliers in Latin America. The most recent push has been Unidos por el Agua, a multifaceted program to connect homes that, for one reason or another, are not part of the official system. It is slated by the end of 2019 to connect more than 40,000 additional families to official water and sanitation services.

Federico Gutiérrez, mayor of Medellín

Federico Gutiérrez, mayor of Medellín

The extra uphill mile

Most of those homes are located in the hillsides above downtown Medellín, in neighborhoods like Unión de Cristo, a collection of improvised brick and tin houses draped over steep slopes first settled — or squatted on, if you prefer — by Colombians facing violence in places like the Pacific department of Chocó.

On one sunny afternoon in September, Fabián Matallana and Arnulfo Álvarez, employees of a contractor working as part of the Unidos por el Agua program, were crouching over the foot-deep opening in a narrow footpath in Unión de Cristo. In orange vests and yellow helmets, the men were preparing to connect a line of high-density polyethylene piping that will bring potable, metered city water to the house of a man they know as Don Pedro.

Critically, Unidos por el Agua is not just about water — it has aspects of a community outreach program as well. Matallana, 36, and Álvarez, 25, were among 20 or so workers on the project who were hired from the neighborhood, which is why they kn0w Don Pedro. “Here we’re all united,” said Matallana, who lives a few blocks away with his wife and six-year-old daughter. “Wherever we’re working, someone comes out and says ‘What’s going on, neighbor?’ and then another comes out. They know us everywhere.” That has helped the program avoid the kind of skepticism or outright hostility that sometimes faces utility workers in similar neighborhoods in other Latin American cities.

Unidos por el Agua has also effectively brushed aside a question often asked of such initiatives: Does hooking “irregular” neighborhoods up to utilities encourage more such neighborhoods to appear? City officials have preferred to focus instead on the public health benefits, and a broader message of inclusion. “It’s our way of saying to people, look, you are a part of a society, you are not alone,” Federico Gutiérrez, the current mayor, told AQ. “It’s a comprehensive program, it’s not just water. Water is an excuse for going in, so that the government can come in with comprehensive interventions.” Medellín also famously has a cable car system that links poorer neighborhoods in the hills to Colombia’s only metro.

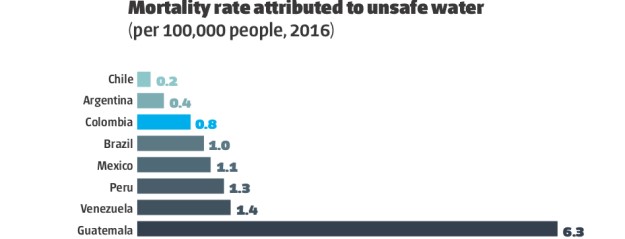

Source: World Health Organization SDG 3.9.2

Source: World Health Organization SDG 3.9.2

The city is also flexible when it comes to regulations designed for more “formal neighborhoods,” recognizing that installing water systems in low-income neighborhoods often brings unique complexities. In some areas, for example, it would be impossible to install pipes as deep as standards require without risk of destabilizing the earth, potentially leading to landslides. Yet that earth was already being destabilized by what the Colombians call “artisanal” water and sewage systems installed by local residents so, the argument went, loosening the rules would actually lead to safer results.

The work goes beyond manual labor. “We generate ownership and empowerment within the community,” said Oscar Betancur, a planning and social development specialist with epm. He calls the work “70% social and 30% technical. They construct it as their own, really their own.”

That helps with establishing a culture of payment for water services — for many, it is the first time paying for water — and reduces the chances of vandalism.

The job also involves a certain amount of conflict mediation. On a recent afternoon, Betancur was walking in La Iguaná, a neighborhood recently connected by Unidos por el Agua, when he was approached by an irritated María del Rosario Aristizabal, who urgently wanted to lodge a complaint about an equipment box for the house next door that workers had installed on her property.

“I may be ignorant because I haven’t studied, but I know my rights,” she said. Betancur calmed her down and took down her information. It was, he said later, an example of just how sensitive residents can be about the property they may not even hold legal title to. Another day, in Unión del Cristo, he pointed out an EPM forestry engineer who had been called in to see if a beloved casco de vaca tree could be saved during construction.

“There are some situations that are only resolved on a day-to-day basis,” he said.

Learning to pay

Similar programs elsewhere have collapsed — or struggled with low resources — because new customers don’t pay their water bills. Several programs make services more manageable for families that previously got free, if unofficial and undependable, water. The city’s Mínimo Vital de Agua Potable, a 10-year-old program that has since spread elsewhere in Colombia, provides qualifying low-income households with the 2.5 cubic meters (about 660 gallons — derived from World Health Organization estimates of minimum water requirements) per person at no charge. As part of the program, social workers train participants to save water by, say, turning off faucets while washing dishes or brushing teeth and reusing water from the final cycle of the washing machine to wash the bathroom.

“They come every year” said Adriana Amalla López, who lives in La Iguaná. “They update our information, ask how we’re doing, and always congratulate us since we use less than we’re allotted, so the bill comes to zero.” About half of the 51,000 participating families avoid payment altogether.

For the others, there’s the prepaid option, where residents pay for water as they go, much the way they would for a prepaid cell phone plan. Even that rate is subsidized: Colombia divides its population into six official socioeconomic strata, with each stratum paying utilities (among other things) on a sliding scale. Strata 5 and 6 subsidize 1, 2 and 3; strata 4 pays market rate.

With pollution dramatically reduced, a riverside park is now under construction.

With pollution dramatically reduced, a riverside park is now under construction.

Meanwhile, Medellín and the region are pushing their citizens to interact with the water supply in ways that go beyond the waterside park. Years ago, as water tanks situated in the surrounding hills were engulfed by urban expansion sprouting up around them, many ended up as forbidding, dark spaces, surrounded by fencing and guarded by security forces. Fourteen in the city (and two outside) have now been transformed into strikingly attractive community centers and parks called UVAs, or Unidades de Vida Articulada.

“One of the UVAs’ objectives was to illuminate the dark corners of Medellín,” said Edison Raigoza, an educator who teaches workshops at UVA La Armonía, in the Santa Inés neighborhood.

La Armonía is a bit different from other UVAs: its water tank is underground, its top exposed, giving it more the look of a pool, complete with a “geyser” spraying water high into the sky. There’s no swimming in the city’s drinking water, but on a recent afternoon, children played in regularly erupting spouts along its edge, as two 18-year-olds, Dayron Rodas and Cristián Durán, members of a local performing arts school, practiced a male duo salsa routine nearby.

This new park in the La Armonía neighborhood sits on top of a giant water tank.

This new park in the La Armonía neighborhood sits on top of a giant water tank.

“It’s a really pleasant space,” said Rodas, “because it’s not just a park to play in, but a place that integrates arts and culture.” It attracts so many visitors day and night — there is a regular film series — that businesses have sprung up around it, like Cafeteria UVA and a restaurant called Delicias La Armonía.

That afternoon, teenagers crouched over their phones outside the center’s five classrooms, sucking up the free wi-fi, and a group of grade schoolers were participating in a class on digital storytelling run by a teacher from the University of Antioquia. She had asked students to identify the emotions portrayed by the faces she was flashing on the screen, including smiling children (“Happiness!”) and a scowling Malcolm McDowell from A Clockwork Orange. (“Anger! Revenge!”)

Considering Medellín’s plentiful water resources and the mammoth presence of EPM, it is tempting to conclude that the city might be a difficult example to follow. Mayor Gutiérrez, however, disputes that.

“We started at some point,” he said. “I think that any city, any society can pursue the objectives and the model of city that it wants. And it’s also a message that what is public can also be efficient. People have often said that public entities are inefficient, a policy of the left. But for me, bringing water to a community is not a matter of right or left.”

“It’s like security: it’s a human right.”