To be 18 in Latin America today is to believe anything is possible.

After all, today’s young people have grown up in a time of almost unprecedented growth and opportunity. They are the first raised in a Latin America where the middle class outnumbers the poor. They are far more connected to the world via those ubiquitous smartphones – and have higher aspirations to match. About 84 percent of them believe they’ll reach their professional goals more easily than their parents did, according to a global survey by the Citi Foundation. No other region was more optimistic, the poll showed – not even Asia.

They’re coming of age as birth rates plummet and the large, traditional Latin American family becomes a thing of the past. This could pay big dividends: 15- to 24-year-olds are now 20 percent of the population, a bumper crop of young, productive workers that could transform the region.

Hope can be a powerful thing – and a welcome break from the fatalism that sometimes characterized past generations.

But if all this talk of great expectations is setting off your alarm bells… well, you are not alone.

Are the region’s schools really that much better than they were 25 years ago? How badly will the recent economic slowdown across much of Latin America frustrate young people’s aspirations? Are crisis-plagued governments focused enough on the future? Will this generation lash out if it doesn’t get what it wants?

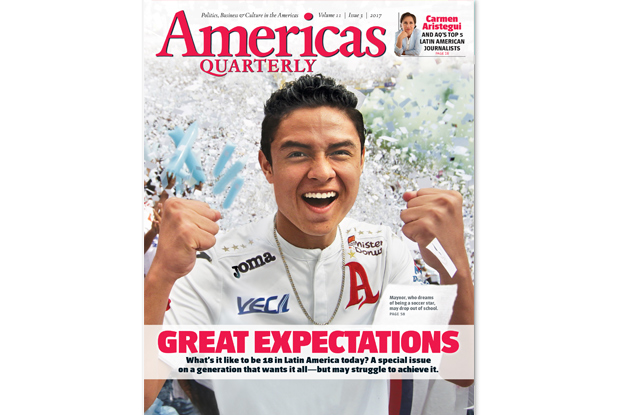

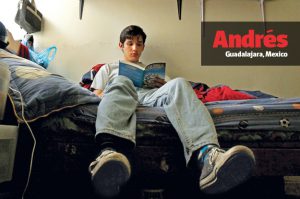

To find out, we at Americas Quarterly asked four journalists to follow four young adults over a period of eight weeks: Sabrina in Rio de Janeiro; Andrés in Guadalajara; Lesly in Lima; and Maynor (pictured on our cover, above) in San Salvador. (To protect their privacy in an era where everyone is searchable forever, we withheld their last names.) Separated by culture, class, race and language, not to mention thousands of miles, their experiences were bound to be disparate. Yet it turns out they do have much in common.

Indeed, they’re part of a broadly defined middle class, secure enough in their everyday needs to project themselves into the world beyond, through study, social media or travel. They see opportunities and leverage their passions – for chemistry, for soccer, for communications, for church – and their resources – parental, communal, academic – to aim higher.

Some of the hurdles our four subjects face are economic, like the instability that forced Maynor to shift from learning to earning so he could help at home. Some are structural, including unsafe neighborhoods like the one Sabrina has to navigate. We also found schools that don’t offer working students adequate skills or flexibility; deficient public transportation that steals time from study or sleep, requiring Andrés, for example, to spend four hours commuting every day; and government investment that favors the old, relegating a growing number of young workers to unemployment or to informal labor markets where they will languish in dead-end jobs. Some young people, like Lesly, have the resources to travel and seek the expertise they needs to get ahead, but she’s an exception.

The good news is that many of the hurdles we’ve uncovered have policy solutions. Governments should resist the temptation to spend primarily on the old, and work to improve not just education systems but also infrastructure across the board. Smart, pro-business policies will also help ensure the creation of decent jobs that can keep young people engaged in society – and out of trouble.

Indeed, governments intent on growth, not just now but over the next decades, would do well to take a look at Sabrina, Andrés, Lesly, Maynor and their peers. Their prospects are also those of Latin America.