George Washington, the first president of the United States, ran for re-election just once, in spite of being tremendously popular and receiving countless pleas from his supporters to remain in power. He thus started a healthy U.S. tradition that lasted a century—until Franklin Delano Roosevelt chose to break it by running for re-election twice. After this one-time alteration of the constitutional order by an incumbent president, in 1951, the United States congress approved the 22nd Amendment, which codifies Washington’s tradition and effectively prevents multiple re-elections.

Something very similar has happened all over Latin America since the region achieved independence from Spain. Numerous constitutional reforms reflect legitimate changes, but many others have been promoted dishonestly by rulers who seek only to benefit themselves. The signing of the Inter American Democratic Charter (IADC) in 2001 by the member states of the Organization of American States (OAS) showed that the rulers who abuse constitutional powers to extend their terms have no place in a community of democratic nations.

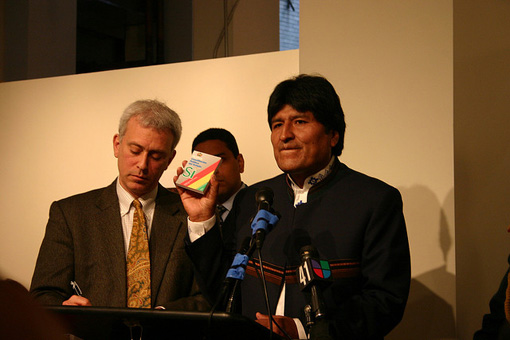

Last month, Bolivia’s Constitutional Tribunal cleared President Evo Morales to run for re-election for the second time in 2014 (also referred to as “re-re-election”) even though the constitution signed by Morales in 2009 establishes that incumbent presidents can only run for re-election once. Several years earlier, in 2000, the National Jury of Elections of Peru cleared President Alberto Fujimori to run for re-election for a second time, in spite of the fact that the constitution drafted by Fujimori in 1993 allowed for only one re-election.

Fujimori once argued that the elections that initially bring a president into power do not count in the overall tally if they occur before the “refounding” of the country—that is, under a previous constitution (the 1979 constitution in the case of Peru, and the 1967 one in the case of Bolivia). To counter this argument, the Bolivian opposition managed to include a provision in the 2009 constitution that ensured that Morales’ first term did count. Thus, the text of the “First Transitory Disposition,” states: “Any terms preceding the effective date of this Constitution will be counted towards the total number of terms established herein.”

Disregarding the universal legal principle that “where the law does not distinguish, we ought not to distinguish” (ubi lex non distinguit, nec nos distinguere debemus), Bolivia’s Constitutional Tribunal, whose magistrates were elected by popular vote in 2011, ruled that:

“[i]t is absolutely reasonable and in accordance with the Constitution to count the terms, for both the President and the Vice President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, from the moment in which the current constitution refounded the State and, hence, created a new legal and political order.”

In 2009, in a similar exercise of constitutional alchemy, the Supreme Court of Justice of Nicaragua cleared President Daniel Ortega to run for re-election, even though the Nicaraguan Constitution (Article 147) expressly prohibits it. According to the court, the constitutional prohibition was “inapplicable” since it violated the president’s fundamental right to “legal equality” in relation to members of the legislative branch—who, according to another article of the Constitution, can run for re-election. Famously, a Nicaraguan judge justified this decision by saying: “If [Álvaro] Uribe does it, it’s ok, if [Oscar] Arias does it, it’s ok; if we do it (…) and we speak out against unconstitutionality, then it’s wrong.”

The Nicaraguan judge is wrong. The constitutional reform championed by President Uribe in 2004 to make his re-election possible was also “wrong,”—unlike, for example, the 1993 constitutional reform (via the judiciary) in Costa Rica that allowed the discontinuous re-election (after 16 years) of President Arias. The latter reform must be considered a democratic one, given that—unlike Uribe—it was not the incumbent president who promoted it while in power.

The IADC establishes among the essential elements of democracy the “access to and the exercise of power in accordance with the rule of law” (Article 3), which includes the principle of alternation of power, as evidenced by the preparatory works on the IADC (see interventions by Chile, Peru and Venezuela here)—as well as by the fact that this document was approved mainly in response to the erosion of democracy under Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, who used constitutional reform to pave the way for his two re-elections.

This is why the violation of the principle of alternation of power does not take place simply because of the constitutional authorization for a presidential re-election, but whenever this authorization is a product of a constitutional reform promoted by the incumbent ruler with the objective of extending his own powers, either temporarily or substantially.

The democracy clause established in the IADC (Articles 3, 4 and 17 to 21) grants the Secretary General of the OAS and any member state the power to summon the Permanent Council and the OAS General Assembly to analyze these types of situations. In the event of any erosion of democracy (or “alterations” of the constitutional order that seriously impair the democratic order), the OAS must create diplomatic monitoring missions to prevent an “interruption” of the democratic order and eventually suspend the anti-democratic governments (whether because they came to power through a coup, or because they eroded democracy from within).

The IADC can be applied in two ways: preventively and correctively. In its initial stages, the democratic erosion must lead to the “preventive” application of the clause as a means to pressure the government to stop and roll back its anti-democratic actions. If the erosion continues, the OAS must then consider that there has been an interruption that seriously impairs the democratic order and the clause must then be applied “correctively.”

Under this framework, the constitutional reforms carried out by Peru’s Fujimori in 1993, Argentina’s Carlos Menem in 1994, Brazil’s Fernando H. Cardoso in 1997, and Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez in 1999—which authorized the re-elections of those presidents—constituted actions that eroded democracy and violated the principle of alternation of power. However, it is only since the codification of this principle in the 2001 IADC that constitutional reforms allowing for the immediate re-election of incumbent presidents should have triggered preventive action from the OAS. To prevent anti-democratic constitutional reforms under penalty of suspension, the OAS should have applied the democracy clause against the governments of Uribe in 2004, Rafael Correa in 2008 and Morales and Ortega in 2009—and should activate it now, in light of the overtly unconstitutional ruling of the Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal that validates Morales’s bid for a second re-election.

In 2009, the OAS should have applied the democracy clause to the government of President Chávez when it modified the 1999 constitution (drafted by Chávez) to allow for his indefinite re-election—something unheard of among the governments of the continent, except for Cuba.

It is important to note that, in principle, indefinite re-elections can be as legitimate as the complete prohibition of re-elections (as in Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Paraguay), immediate re-election for one term (currently allowed in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and the United States), or re-election in discontinuous terms (allowed in Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay). But re-elections only gain their legitimacy when promoted by stakeholders beyond the immediate beneficiary and as a result of the checks and balances among powers and political parties in a democratic society.

In fact, the possibility of indefinite re-elections—as a democratic ideal and as an incentive for good governments—found in Alexander Hamilton, an Enlightenment author, one of its most notable supporters. Hamilton, along with James Madison and John Jay, wrote a series of press articles between 1787 and 1789 defending the proposed American constitution, which provided for indefinite re-elections (see the Federalist Papers, no. 69). However, unlike Fidel Castro or Hugo Chávez (or Alfredo Stroessner and Rafael Trujillo), Hamilton did not propose indefinite presidential re-elections as a means to perpetuate himself or his heirs in power. President George Washington, who could have benefited from indefinite re-elections, personally eliminated any danger of presidential authoritarianism by selflessly renouncing a second re-election.

It is time the OAS applies the democracy clause against those presidents who, disregarding the very rules under which they were elected, abuse their power to extend it indefinitely.