The first time I tried to visit Suchitoto, it was a town under siege. Left-wing guerrillas who held the nearby Guazapa volcano were trying to drive the military out. Three-quarters of the town’s 40,000 population had fled or been killed – and life was miserable for those who remained, as sabotage attacks cut off electricity and water supplies for two long years. The roads around the town were mined, and bus service suspended. Although only 30 miles from El Salvador’s capital, Suchitoto was essentially cut off from the world.

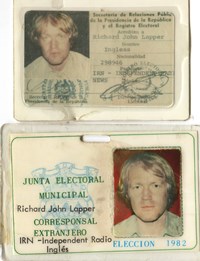

I was a young reporter covering Central America’s wars of the early 1980s, and I don’t believe our rented car with its “prensa international” placard ever made it past the obstacles. And perhaps it was for the best. One evening, on our way back to the capital, we were stopped by a group of obviously drunk government militiamen brandishing their rifles and leering menacingly. A few weeks later, troops hijacked a group of Dutch journalists who were seeking to make contact with guerrillas nearby. Our colleagues never made it home.

Today, at first glance, Suchitoto seems to have left that bloody past behind. It is now, perhaps improbably, one of El Salvador’s best-known tourist towns. Small hotels, cafes and art galleries have emerged. On a visit this January, I saw a bright white church and cobbled streets. Schoolchildren in neatly ironed uniforms crowded around stalls selling sliced papaya and watermelon, as a peasant farmer in a wide-brimmed straw hat trotted by on horseback.

Shiori Seo, a 23-year-old aid worker from Tokyo, was in her first week of classes at the Pájaro Flor language school – and obviously charmed by the place. “The old buildings, the lake and the people are, what do you say, so amable,” she said, laughing, throwing in a bit of her newfound Spanish for good measure.

Dig a bit deeper, though, and one quickly discovers that much of Suchitoto is just as troubled as it was back then. Yes, the city center is fairly quiet. But on the poorer edges of town, two armed gangs — Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 — are engaged in a turf war that has made El Salvador the world’s deadliest country not named Syria. The gangs, known as maras, operate with impunity, extorting “war tax” from many businesses. “If you dare to report this to the police, they kill you,” a businessman told me, asking that his name be withheld. “People prefer to pay what they can and continue working. It is like a disease, a social plague. We seem to be losing control completely.”

Dig a bit deeper, though, and one quickly discovers that much of Suchitoto is just as troubled as it was back then. Yes, the city center is fairly quiet. But on the poorer edges of town, two armed gangs — Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 — are engaged in a turf war that has made El Salvador the world’s deadliest country not named Syria. The gangs, known as maras, operate with impunity, extorting “war tax” from many businesses. “If you dare to report this to the police, they kill you,” a businessman told me, asking that his name be withheld. “People prefer to pay what they can and continue working. It is like a disease, a social plague. We seem to be losing control completely.”

With this level of violence and impunity, it is hard for good projects to survive. Even the most promising entrepreneurial ideas tend to wilt away. In Suchitoto, restaurants and tour operators have seen business fall off. Tour guides have stopped visiting certain landmarks, including a local waterfall, without police protection. The Pájaro Flor school, which following its inception eight years ago profited by persuading international aid agencies to send their volunteers there, is in dire trouble. No one is booked in to take classes once Seo, the Japanese student, and her colleagues complete their courses. Nelson Melgar, the school’s director, is desperately disappointed. “It is so sad for us, the generation that had to live through the war,” he said.

I confess it was sad for me too. I began my journalistic career in Central America at a time when it was wracked by terrible violence. There have been a lot of positive changes since then, but during a three-week reporting trip to the countries that make up the region’s so-called Northern Triangle, it was surprising to see how much fear, insecurity and bloodshed still dominate the lives of ordinary people. I spent a week each in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras – and tried to see those countries beyond the rather narrow middle-class city centers that tend to dominate international perceptions.

I retraced some of my steps from 35 years ago and met many of the people I once knew, as well as others who grew up in the post-war period. In these conversations, I tried to discover: What will Central America’s Northern Triangle look like in another 35 years? Will this still be a region marked by failure in the year 2050? Or will the region be able to finally bury its violent past and become a somewhat better place?

During my trip, I saw the kind of energy, idealism and small-scale triumphs that are often ignored by the media and foreign governments, and would seem to illuminate a promising path forward. But I also saw the pervasive fear and government dysfunction that have made the Northern Triangle an exporter of refugees and one of the world’s most troubled regions.

Which future lies ahead? Either seems possible.

Worse than the ’80s

As incredible as it may seem, some commentators say the situation is even graver now than in the 1980s. One is Joaquín Villalobos, once one of the top commanders of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the left-wing guerrilla group that during that era fought El Salvador’s U.S.-backed armed forces to a standstill. “This is the worst social tragedy of our history,” says Villalobos, who split with his former FMLN colleagues in the 1990s and is now a consultant based in Britain. “It is worse than during the war, because now there is less hope.”

Villalobos says his country is living through a vicious cycle. Low economic growth leads to high unemployment, which leads people to leave the country. Those left behind depend heavily on remittances, the money their relatives send home. Meanwhile, thousands of young people, unable to find jobs and often living in families broken by the breadwinners’ departure, rely on the maras for a basic income. The resulting insecurity further depresses economic activity and leads to even more migration, and so on. Matters are especially acute in El Salvador, but the same cycle is visible in Honduras and Guatemala too.

A lack of resources in the public sectors has made things worse. On average, the Northern Triangle countries raised the equivalent of 13.6 percent of their gross domestic product in taxes in 2015, compared to an average of 24.4 percent for Latin America’s seven largest economies. The average for Western European and North American countries is higher still.

A blown-up bridge in El Salvador in 1981.

A blown-up bridge in El Salvador in 1981.

One result is underfunded and short-staffed police, who are often invisible in poorer areas. Violence is increasingly an important factor driving migrants north to the United States. Last year Elsa Ramos, a sociologist at the Technological University of San Salvador, surveyed 747 migrants who had been repatriated. Forty-two percent said they left home because of the threat of violence, compared to just 5 percent who gave that answer in 2013.

Just as in the 1980s, the crisis is not always immediately apparent to a visitor. The middle-class heart of the capital, San Salvador, often seemed peaceful enough when I first visited. Returning from our reporting trips, we would happily eat pupusas (maize pancakes) and homemade paella and drink Pilsener beers in the attractive small restaurants that clustered around the Camino Real hotel, where most journalists used to stay. That area is more aggressively commercial today – full of shopping malls and fast food restaurants – and the roads outside are much, much busier with traffic. It still doesn’t feel particularly dangerous.

“It is a perverse situation,” says Villalobos. “When you arrive it appears as though nothing is happening. But the gangs are where the poor are and where there is no state.”

The gangs are themselves a legacy of turmoil. Many who emigrated to Los Angeles in the 1980s, or their children, were deported back to Central America starting in the 1990s. They brought back L.A. gang culture, including tattoos and a penchant for score-settling. Yet there are other echoes of the past as well. For example, the FMLN once exercised control over relatively tiny territories such as Chalatenango in the north or Morazán in the east, where Villalobos’s guerrilla units were based. Now their criminal successors seem to have borrowed similar ideas, although their “rear guards” are in the ramshackle peripheral areas of Central American cities and they are expanding into economically vulnerable rural zones.

“The police might say that they can go where they want, but people living in these communities call it a criminal dictatorship,” said Estela Armijo, a former policewoman who now works as a consultant. Even speaking publicly about the need to prevent violence is to invite a reprisal, she said. “They charge taxes, you can’t go to communities that are run by opposing groups of maras, and you can’t speak with the police.”

A Salvadoran court declared Maras to be “terrorists” in a 2015 ruling.

A Salvadoran court declared Maras to be “terrorists” in a 2015 ruling.

The results are horrifying. El Salvador’s homicide rate reached 103 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2015, up from 68.6 in 2014 and 43.7 in 2013. So far this year, the upward trend is continuing. The trends are also visible in Honduras and Guatemala, which were less deadly last year but still ranked as the third and fifth most perilous places in the hemisphere. Nicaragua has been more peaceful, perhaps thanks in part to a legacy of community policing from the 1979 revolution, although its economy is a mess and incomes are among the region’s lowest.

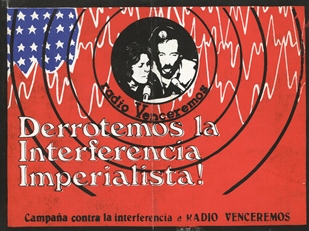

If the fuel of the violence in the 1980s was ideology, today it is organized crime and – in much of the region – drugs. The intensification of the drug war in Colombia (as a result of the U.S-led Plan Colombia from 1999), and then Mexico (where the government intensified its crackdown against the drug trade in 2006), led to a shift in export routes. With their weakly policed interiors and Caribbean coasts, plus easily corruptible officials, Honduras and Guatemala became prime way stations for narcotics headed to the United States. The gangs often sponsor social spending or infrastructure plans to cultivate popular support. The drug trade has also exercised influence among some politicians and business leaders, a fact underlined by the recent extradition of several senior Honduran executives.

The search for solutions

Thankfully, there have also been numerous positive developments over the past 30 years – some of which have not received the international attention they deserve.

When I first visited the region, at the height of the Cold War, it was characterized by dictatorships or extremely weak democracies. When there were elections, they were routinely fixed in favor of parties backed by the military and landowning elites. Politicians proposing social reforms, no matter how moderate, were routinely gunned down or forced into exile. Even the Christian Democrats, similar in outlook to the Democratic Party in the United States, were beyond the pale, derided as “watermelons”: green on the outside (the party colors) but socialist red on the inside.

Today, all of the region’s countries are democracies. They are not perfect – the 2009 coup in Honduras showed how fragile progress is. But there is a newfound pluralism in the region that is undeniable – and is already having positive real-life consequences.

Take the example of Nineth Montenegro, who was plunged into political activity when her husband was murdered by Guatemala’s military in 1984. In ensuing years, she only narrowly escaped being killed herself. Today, she is a moderate left-wing member of Congress who works just a block or so from buildings where “subversives” used to be tortured.

Last year, Montenegro played a prominent role in the anticorruption probe that eventually led to the downfall of President Otto Pérez Molina. At one critical point, she and a small group of supporters spent a night “occupying” Congress to press legislators to vote on a bill to lift the president’s immunity. On the morning I saw Montenegro, several senior military officers who had led the repression of the early 1980s were picked up as part of a corruption crackdown.

We marveled at how utterly unimaginable all this would have been back then. “The Guatemala you knew three decades ago no longer exists,” she told me. “Society is advancing with giant strides. There is a new dynamic generation that is very attentive to the country’s problems and very vigilant.”

The region’s economies have changed for the better in some ways too. On the eve of the 1980s, Central America was very heavily dependent for its foreign exchange on only a handful of tropical crops: coffee, bananas, sugar and cotton. A few food, drinks and textiles companies did reasonable business. But that was about it.

These days, earnings from tropical agriculture are dwarfed by a maquila export sector – in which imported parts and components are assembled for export, mainly to the United States. Roughly 350,000 people in the Triangle countries are employed in such plants. There has been some growth, too, in so-called nontraditional agricultural exports such as palm oil. This diversification has been helped considerably by the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) with the United States in 2005. Over the last decade, the value of merchandise exports from the Triangle has increased by more than 70 percent.

Perhaps the biggest change has been the huge growth of remittances, although that has been something of a mixed blessing, helping subsidize consumption and alleviate poverty but doing relatively little to stimulate job creation.

The pace of progress in Central America over the past three decades has significantly trailed other regions in Latin America. Obtaining and keeping a job seems to involve almost heroic endurance and self-sacrifice. Six-day weeks and 12-hour days seem to be common in the under-productive services sector. Juan Carlos Zapata, director of Fundesa, a Guatemalan business organization, said – astonishingly – that in his country labor productivity has not increased at all since 1978. The results are unemployment, low wages and a host of other economic woes. (See article).

Any solution to the region’s ills must address the mass of young jobless people who are induced to either emigrate or join gangs. Young, technocratic policymakers in the countries’ capitals know this. Meanwhile, there is an upcoming opportunity.

The $750 million U.S. aid package negotiated for the Northern Triangle countries is less than the Barack Obama administration originally sought. Relative to both past commitments and money pledged elsewhere in the world, it is modest. Nevertheless, it is a useful start. So the question is: What should the funds focus on?

Islands of excellence

There are certainly some positives to build upon, including the rapid expansion of mobile phones and finance, manufacturing (especially in Honduras), and the recent success of business outsourcing in Guatemala.

Yet, if one takes a hard look at the region’s myriad challenges, it’s clear that farming will be an absolutely critical part of the Northern Triangle’s future. Agriculture has been declining as a percentage of GDP but it continues to be a very significant source of jobs, with one of every three Guatemalans and Hondurans employed in the sector. What’s more, impoverished rural areas are experiencing the greatest social difficulties and are generating the greatest number of migrants.

The rural crisis has become particularly acute as a result of changes in climate. Across Central America’s dry corridor, which stretches from the Guatemalan high plains to El Salvador and into Honduras, temperatures have risen and rains have become far less reliable. That’s in part because of the effects of El Niño (and La Niña) climate phenomena but is also in line with longer-term weather trends. Small farmers in all three countries have seen maize yields drop by as much as 75 percent. Many are leaving the land as a result.

The rural crisis has become particularly acute as a result of changes in climate. Across Central America’s dry corridor, which stretches from the Guatemalan high plains to El Salvador and into Honduras, temperatures have risen and rains have become far less reliable. That’s in part because of the effects of El Niño (and La Niña) climate phenomena but is also in line with longer-term weather trends. Small farmers in all three countries have seen maize yields drop by as much as 75 percent. Many are leaving the land as a result.

Leonardo López, who farms maize and coffee near San Martin Jilotepeque in Guatemala, is staying put for the moment but said many of his neighbors have sold their land already, often investing the proceeds in a new car or motorbike. “You have to begin with agriculture because these rural zones are (the ones) expelling people,” said Victor Umaña, a professor at the INCAE business school in San José, Costa Rica.

One possible focus for aid efforts would be to support a shift in farming methods that is helping subsistence farmers cope with less predictable rainfall. Some agronomists argue that farmers need to adapt to less predictable rainfall by growing more trees and using so-called mulches (made from leaf mold and other compost) to protect the soil and help it preserve nutrients and retain rainwater for longer. They also need to stop plowing. Ian Cherrett, a consultant and former senior official at the Food and Agriculture Organization said that with governments in El Salvador and Honduras supportive of such methods, thousands of small farmers in both countries have already adopted the new ideas.

Beyond that, however, Central America could probably do more to exploit its potential as a producer of labor-intensive but high-value-added crops such as vegetables, fruits and high-quality coffee or cocoa beans. Umaña described this sector as “precision agriculture,” because of the way it carefully manages growing conditions and takes advantage of microclimatic diversity.

I found one good example at the Cuatro Pinos Cooperative at Santiago Sacatepéquez, an hour from Guatemala City, which exports more than $30 million a year of haricot beans and other vegetables. On the morning I visited the Santiago temperature-controlled factory, there were dozens of Kaqchikel Mayan women workers wearing blue overalls, white head scarves and face masks as they sliced, cleaned and packaged four varieties of mini carrots.

The business generates jobs on a much bigger scale, with more than 3,000 associated suppliers based in 16 of the country’s 22 departments earning a living from the cooperative. “Everything is done by hand. We create huge demand for labor,” said Tulio Garcia, who originally launched the business in the late 1970s and has been its director for the last 15 years.

Garcia said the vegetables can be six times more remunerative than the maize and beans alongside which they are typically cultivated, arguing that families dedicating half their plot to vegetables sold to Cuatro Pinos can quadruple their incomes.

Cuatro Pinos is also capitalizing on a broader trend in international markets: Demand for microvegetables – which are viewed as rich in flavor and are popular among upmarket chefs – has been a powerful force for growth. Demand for baby carrots increased by about 50 percent in 2015, for example.

Garcia is enthusiastic about the broader potential, arguing that greater public investment in irrigation would allow his own group to grow vegetables on an additional 2,000 hectares, increasing its land area by two-thirds. “We need a huge shift in agriculture, moving away from maize and beans with minimum yields to more value-added crops.”

The group, which is owned by its 560 members, has done much to promote social welfare by, for example, offering education grants to the families of employees and associates, who are often from the disadvantaged indigenous communities. Rosa Linda Rajpop, 34, is one beneficiary. After joining the cooperative as a secretary 16 years ago, she was able to go to university and now runs the group’s export department.

Another company making similar kinds of advances is Agrolíbano, a successful melon exporter from the southern Honduran department of Choluteca. In the 1980s, Choluteca was a center of a cotton industry that became disastrously dependent on the heavy application of chemical pesticides. These days, Agrolíbano has developed sophisticated “near-organic” techniques of disease control, allowing it to meet the toughest European standards and diversify its markets away from the U.S.

It has also developed clever ways to grow its melons that enable the fruit to survive for longer and be competitively sold in the distant North Asian market. Over the last decade or so exports have been growing at an average 4 to 5 percent per year and exceed $50 million a year. Keny Molina, commercial director and nephew of the founder, said the secret is care and attention as the melons are grown and transported. “We feed them as carefully as athletes,” he said.

A big challenge to replicating these success stories, though, is education. Without it, the countries may lack a rural population that can better apply advanced technologies and management methods. One of the most encouraging examples I came across was at the National Autonomous University of Honduras. A decade ago the university was struggling with the legacy of chronic mismanagement and high student failure rates. The crisis was so bad that with competing private colleges gaining ground, there were fears the institution might be closed. “Teachers frequently didn’t go to classes and nobody worried about it,” said Manuel Torres, a member of the university’s executive.

Under its current rector, Julieta Castellanos, a sociologist who took over in 2009, order has been restored to the management of teaching. Student failure rates have been cut by about half and much more effective use has been made of investment funds, with plans to build sports halls and other facilities actually implemented. Progress has been made, too, in introducing more vocational courses, specializing in areas such as fishing, forestry and market gardening.

Torres said there has been some resistance from teachers’ unions but, “We have had to oppose academic populism and insist that the university is not just for the teachers, officials or students, but for the whole of society.” In the end the change has amounted to a simple recipe. “It is about efficient, honest administration.”

Security challenges

Investments in these kinds of projects could accomplish a lot. But after three weeks in the Northern Triangle, and talking to dozens of people, one overarching truth was clear to me: Until countries make more progress in solving their security and governance difficulties, little else will matter. Just as peace was essential for the progress of the 1990s and 2000s to take place, so security, including effective judiciaries and police forces, is now a prerequisite for further advance. As Villalobos put it in the case of El Salvador: “Nothing is possible unless the state establishes its control in all the national territory.”

Suchitoto looks like a typical tourist town – at first.

Suchitoto looks like a typical tourist town – at first.

Here too, there are a few positive signs. In Guatemala and Honduras, murder rates have declined and some institutions have shown considerable independence and courage. In Guatemala, the improvements culminated last year in the removal from office of Pérez Molina and his deputy, Roxana Baldetti. Investigations by the UN’s international commission on corruption in Guatemala that led to Pérez Molina’s departure, backed by popular pressure and strong lobbying from international organizations, were all central to the change.

There have also been improvements in policing that date back to the mid-2000s, when measures were taken to strengthen the attorney general’s office and legal changes that made it easier for police to use forensic evidence and wiretaps. In Guatemala, “criminal structures have been brought down and crime rates, though high, are coming down,” said Arturo Matute, a researcher with the International Crisis Group.

Honduras’ advance is more recent. Under President Juan Orlando Hernández, a number of powerful organized drug trafficking groups – including Los Valles and the Cachiros – have been broken. Like Colombia, which successfully tackled the drug trade in the 1990s and 2000s, Honduras has been helped by an extradition treaty that has allowed it to call on U.S. assistance in the battle against the drugs lords. Further help is on its way from a Guatemalan-style international anticorruption commission, being supported by staff from the Organization of American States that was set up in January. Homicide rates have dropped sharply, falling to 57 per 100,000 in 2015, more than 20 points lower than in 2014.

“I am significantly optimistic,” said Kurt Ver Beek, a U.S.-born sociologist and director of the Association of a More Just Society, a Tegucigalpa-based NGO that specializes in crime and governance and works with a number of poor communities on these issues. Back in 2012 when the murder rate reached 90 per 100,000, Ver Beek said he was close to abandoning the country where he has lived for a quarter of a century. “It felt like I had invested most of the efforts of my life in something which had very little result.”

Murder rates may have fallen, but extortion is ubiquitous in both Honduras and Guatemala. In Nueva Suyapa, Tegucigalpa, one of a number of poor urban barrios where Ver Beek’s NGO has projects, residents say conditions have improved but they remain frustrated by the continuing influence of the gangs. One person who runs a taxi business in the barrio told me he has to pay three separate extortion payments each week. The outgoing $45 represents a significant dent in his family’s income. As a squad of heavily armed military policemen walked past his house, he admitted that things have improved and “there are fewer deaths. But I have to pay the war tax in order to work here. If I pay, they let me work.”

Murder rates may have fallen, but extortion is ubiquitous in both Honduras and Guatemala. In Nueva Suyapa, Tegucigalpa, one of a number of poor urban barrios where Ver Beek’s NGO has projects, residents say conditions have improved but they remain frustrated by the continuing influence of the gangs. One person who runs a taxi business in the barrio told me he has to pay three separate extortion payments each week. The outgoing $45 represents a significant dent in his family’s income. As a squad of heavily armed military policemen walked past his house, he admitted that things have improved and “there are fewer deaths. But I have to pay the war tax in order to work here. If I pay, they let me work.”

Nor is there any sign of improvement in the poor suburbs of Guatemala City, where gangs still seem to rule the roost. “If you walk into these areas, it’s like it’s another country,” said Edgar Gutiérrez, coordinator of the Institute of National Problems at Guatemala’s San Carlos University. “These zones are out of control.” Gutiérrez cited recent research that shows how criminal power is affecting the attitudes of children. “Thirty years ago they would have said (they want to be) a teacher or a doctor. Now they all want to be gang leaders.”

Press reports suggest that there are, on average, 200 assaults every day on buses, with small groups temporarily occupying vehicles and robbing passengers of their money and telephones. Drivers and ticket collectors work at huge risk, partly because they can be victimized if operators resist demands for money. David Dubon, a retired journalist and former presidential adviser, said that in the first few weeks of January, 15 drivers were killed. “There are one or two deaths every day. If you take a bus you automatically feel nervous,” he said.

In both Guatemala and Honduras, much progress is still needed in the battle against corruption. Matute of the International Crisis Group said that in the face of heightened international pressure, Guatemalan drug lords have been working more subtly. “During the past year there has been less violence. Drug traffickers have been more interested in setting up agreements with local authorities and bringing them into the business.”

In spite of the president’s removal last year, the authorities still have to introduce sufficient change at the tax and customs agency that was at the center of the recent scandal. Tax revenues have not increased since the changes, suggesting the underlying structures and practices within the customs agency remain intact. “They have chopped their heads off,” said Juan Carlos Zapata at Fundesa, which is now pressing the new government to make further changes in senior personnel. Matute agreed, arguing that the corruption networks remain intact in other state organizations. “Hits against them in 2015 were important but not enough.”

Thinking of solutions

Community policing, of the kind that has been developed in Nicaragua and is being promoted by Ver Beek’s NGO in Honduras, is part of the solution. But it is much more difficult to implement in El Salvador, where improvement has been more elusive than in the other countries. Policy has swung between hard-line (mano dura) suppression, favored by the right-wing governments of the early 2000s, and negotiation, initially favored by the left after it came to office in 2009. A truce eventually disintegrated into greater violence and has since given way to a policy of outright repression, which José Miguel Cruz, a professor at Florida International University, described as mano brutal. “They are allowing the police and military to shoot first and ask questions later. They have no accountability.”

Guatemalan authorities destroy a weapon seized from criminals.

Guatemalan authorities destroy a weapon seized from criminals.

Armijo, the former policewoman, is particularly pessimistic. “Even to talk about the prevention of violence is to run a risk. To speak to a policeman in a community is a death sentence,” said Armijo. “We have to have a much more coercive policy. You have to have a hard line because people are so frightened to talk.”

Villalobos, the former guerrilla, believes that with 25,000 police officers facing as many as 65,000 maras, only a radical increase in police numbers will make a difference. He sees a solution similar to what former President Alvaro Uribe did in Colombia – strengthening the state and extending its control to all reaches of the country. “In the end, the solution lies in the multiplication of the state’s power. El Salvador simply cannot defend itself with the number of police that it has. We need to double the number of police and have neighborhood forces that can recover the barrios. “

Such a solution implies two changes. One is a substantial increase in taxes collected by the Northern Triangle’s governments, to bring their resources in line with their peers elsewhere in Latin America. The second change is greater trust – among communities, officials and security forces. In countries with a legacy of division and strife going back to the 1980s and beyond, that may be the biggest challenge of all.

—

Photo Credits: Foreign correspondent IDs courtesy of the author; bridge archived photo courtesy of the author; newspapers Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty; Suchitoto John Coletti/AWL; Radio Venceremos courtesy of the author; gun destruction Jorge Dan Lopez