This article is adapted from our 1st print issue of 2016. For a trial subscrition to AQ for just $1, click here.

The late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, had long envisioned China becoming Venezuela’s biggest oil-sector production partner. So when Rafael Ramírez, then president of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), announced in January 2013 that Russia would produce enough oil with PDVSA by 2021 to become “the biggest petroleum partner of our country,” very few people believed him. It sounded like empty hype.

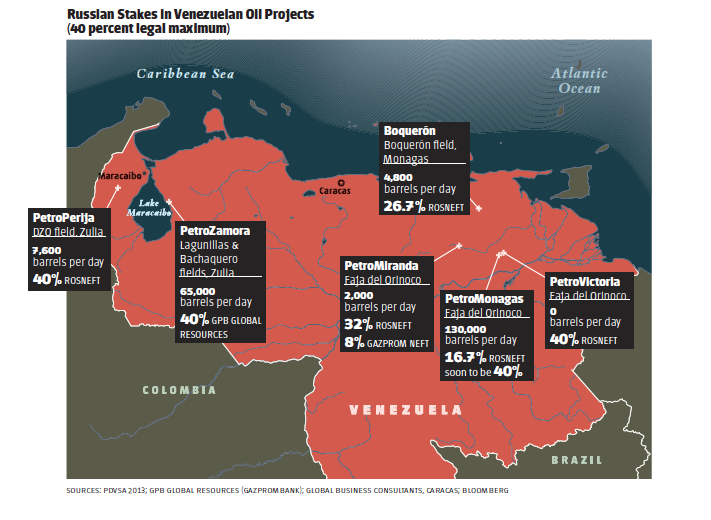

Yet it turns out that Ramírez was serious. Three years later, Russian companies are already producing more oil in joint projects with PDVSA than their Chinese counterparts. Official figures are either unreliable or unavailable, but according to field data provided by Global Business Consultants (GBC), a Caracas-based energy consulting firm, Russia-Venezuela production as of late 2015 was 209,000 barrels per day (bpd), compared to China-Venezuela’s at a bit over 171,000 bpd.

That’s still a long way from meeting Ramírez’s prediction that Russian firms will be producing over 1 million bpd from Venezuela oil fields by 2021. Nevertheless, interviews with knowledgeable sources in Venezuela’s oil sector turn up the repeated comment that the Russians, lately, “are everywhere.” While these sources acknowledge that some leading private Russian companies have given up and left the country, they point out that Russian state-controlled petrogiant Rosneft has remained — and is very serious about producing oil.

Ramírez made his prediction on the same day he met with Igor Sechin, Rosneft ’s CEO. As the capstone to his visit, Sechin had promised to invest $17.6 billion in Venezuela’s oil fields by 2019. Sechin’s promise carried authority: A former deputy prime minister, he has been a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin for over 20 years, and until recently was described as Russia’s second most powerful person.

But Sechin’s senior position in the Kremlin political elite only increased speculation in Venezuela that much more was involved in his pledge than an oil deal. Even prior to his visit, there was already a widespread belief that Russian oil companies were not actually producing any significant amount of oil in Venezuela and that their activity is primarily a cover for weapons deals and corruption. Certainly, Russian personnel’s penchant for being what is seen as “very secretive” about their affairs in Venezuela has fueled this perception.

This speculation can be traced to 2008, a difficult year in relations between Washington and Moscow. After the U.S. Navy delivered supplies to Georgia during the Russian invasion, Moscow accused the U.S. government of encroaching on Russia’s sphere of influence. Shortly thereafter, Putin sent a nuclear warship and bombers to Venezuela in an obvious tit-for-tat. By the time the year was up, then-President Chávez had visited Moscow twice.

The military collaboration has only strengthened since then. Between 2012 and 2015, Russia sold $3.2 billion in arms to Venezuela, making it the number-two buyer of Russian arms globally during that period. And in October 2014, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro pledged another $480 million to purchase 12 Sukhoi-30 jetfighters and to upgrade existing Sukhois in the Venezuelan fleet.

PROFITS OR GEOPOLITICS?

However, those who believe Russia’s interest is primarily oil – and profit – point to Rosneft’s diligent efforts in the oil sector. Rosneft recently boasted, for example, of a country horizontal-drilling record at its Junin 6 field. A petroleum service-sector veteran based in Monagas ticked off a number of new Russian oil projects, noting that local “highly skilled engineers” have been hired to help run them. Paying for arms with oil, he concluded, “does not seem to be a valid reason at this moment to justify the Russian push.”

Anatoly Kurmanov, a Caracas-based Wall Street Journal reporter, agreed. “Oil and gas are the vast bulk of [Russia’s] income,” he said, while arms deals represent “only a few percent” back in Russia. “The [Russian presence] is about business people working to make money in oil and gas.”

Many observers of Venezuela’s oil sector note that Rosneft has maintained its commitment to Venezuela’s oil sector despite its complaints about PDVSA and the ire of nationalists back home who wonder why Rosneft is spending money on Venezuela when it needs to boost home production in the face of Western sanctions. The complaints reflect many of the difficulties encountered by other foreign companies operating in Venezuela, such as PDVSA’s operational and technological dysfunction, as well as the depressed global oil price.

The strains in the Rosneft-PDVSA relationship have not been concealed. At a heavy-oil conference in Maracaibo last October, Kim Gobert, head of Rosneft ’s technical department, openly criticized PDVSA for “not having evolved in technology … since the ‘90s,” noting for example, that the Faja Orinoco field needs to be “re-engineered.”

This reflects frustration over two Faja heavy-oil projects Rosneft has with PDVSA that still lack upgraders and even pipelines, with oil being transported in Chinese-made trucks lacking oil-transfer vacuum-assist systems.

And Rosneft has other complaints. A consultant, requesting confidentiality, said Rosneft recently discovered that about 10 percent of production had gone missing at one field, requiring managers to implement strict inventory procedures and to improve the monitoring of storage tanks to halt pilfering.

He (and others) also explained that while PDVSA now has more reliable payment arrangements available via off -shore escrow accounts, it has been over a year since Rosneft initialed them in October 2014. He noted that Sechin himself had recently clashed with PDVSA over its insistence on splitting these Rosneft contracts into multiple subcontracts. “Four pieces become 40 or 60 pieces of paper,” the consultant said, adding that PDVSA’s excuse that there are “insufficient able personnel” to draw up contracts is more than unacceptable.

“This is real negligence,” the consultant observed, “because we so desperately need all sorts of new production, and here are people willing to do it.”

ROSNEFT’S “LUCK”

Russia began expanding its energy investment in Venezuela after the global economic crisis. Flush with cash, Russia’s leading energy firms – Gazprom, Rosneft, Lukoil, TNK-BP and Surgutneftegaz – formed a National Oil Consortium to consolidate their separate efforts to exploit Venezuela’s fields in October 2008. Within five years, however, Rosneft remained the sole investor, having bought the stakes of its privately held partners, who had decided to sell out for reasons ranging from “uncertainties” created by Venezuela’s business climate to dry holes.

BP’s decision to sell off its high-producing Venezuelan fields, as part of its worldwide effort to pay damages for the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, turned out to be the “real stroke of luck for Rosneft,” according to Antero Alvarez, a Caracas-based consultant. To raise cash, BP had sold its Venezuelan fields in 2010 to TNK-BP, where it had a 50 percent stake with Russian partners (most of it in domestic Russian fields). But, in March 2013, the TNKBP holdings, including the old BP fields in Venezuela, were sold to Rosneft .

In October 2014, four former TNK-BP fields alone were producing about 142,000 bpd out of Rosneft’s total 144,000 bpd Venezuelan production, according to data provided by GBC. The other 65,000 bpd of Russian production, by GPB Associates on Lake Maracaibo, are also former BP fields.

Contacts also report Rosneft has been sending serious experts to boost its production. But, considering that Russia produces well over 10 million barrels of oil per day — 40 percent of it by Rosneft — and is trying to boost domestic production to resist Saudi price pressure and U.S. and EU sanctions, why is Sechin so focused on the relatively tiny fraction of Russian oil production represented by Venezuela?

As Andrej Haug, who works with a gas trading firm in Zurich, and is familiar with Russia, told me, some Russians are openly asking why Sechin is “spending money on Venezuela.”

Participants in Venezuela’s oil sector offer a credible explanation. In interviews, I was repeatedly told that to be taken seriously in Venezuela, one must have a footprint in the oil sector. Rosneft’s dogged interest in production and profits – at least in sufficient amounts to sustain a Russian presence when private Russian firms are unwilling to stay – suggests the message has been heard.

Today, Sechin and Rosneft are earning respect from oil-sector players on the ground, from both inside the Chavista PDVSA and from private-sector professionals familiar with their efforts. Evidently, for Putin as well as for Sechin, Russia’s energy business in Venezuela, as elsewhere in the world, is not separate from geopolitics.

Still, Sechin’s ability to make good on Ramírez’s original prediction of Russia’s commanding role in Venezuela’s oil sector is linked to his ability to overcome the dysfunction of his PDVSA partners in a depressed oil market, and that in turn remains dependent on the tenacity and skill of Russian energy professionals on the ground.

—

O’Donnell is an academic and analyst of the role of global oil and gas markets in geopolitics and development – inlcuding Latin America, OPEC-Middle East, the U.S., EU, Russia and China. He blogs at GlobalBarrel.com