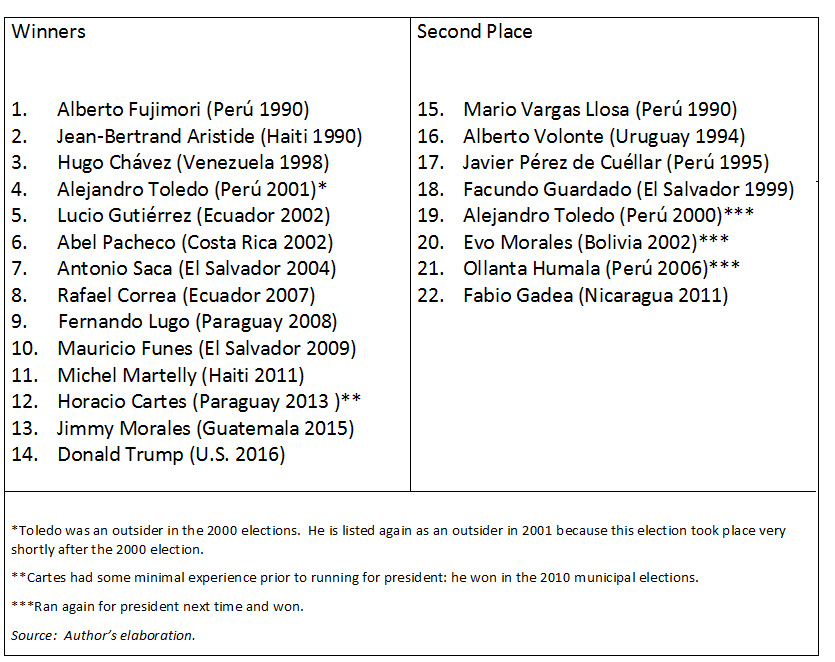

Donald Trump’s victory on Nov. 8 may represent the arrival of a true outsider to the U.S. presidency, but the rise of political newcomers is old hat in Latin America. Since the mid-1980s, by my count 21 outsiders have either won the presidency (13) or come in second place (and three of the eight who came in second eventually secured the top job). With Trump now added to the mix, we can safely say that the phenomenon of outsiders becoming presidents is not so uncommon in our part of the world.

What lessons or theories can we draw from these cases to help us understand the factors that allow outsiders to succeed electorally? Below, I offer some observations about the ways in which Trump’s rise conforms to patterns elsewhere in the region – and ways in which it differs.

But first, let’s define what an outsider actually is. Like many other political scientists, I prefer to define a political outsider as a candidate for the presidency with no recent experience in 1) elected office; 2) running for office; or 3) running a large, nationwide political organization. I also prefer to exclude from this definition candidates who are related to either an ex-president or a leading political figure, in order to sort out political dynasticism, which is a marker of in-group status. Some scholars define outsiders in terms of ideology (candidates with unusual ideas), but this is hard to operationalize. Others prefer a regional focus: those who hail from outside urban power centers. But only the first definition, based on professional experience, allows us to study the real puzzle associated with outsiders: Why do voters trust candidates for whom there is a very thin record or political lineage to examine?

The table below provides the presidents and runners-up who meet this definition. It does not include 16 other outsiders who didn’t do as well electorally, finishing in third place or lower.

What patterns can we discern from this list, and how does Trump fit in? At first, it seems a disparate list of individuals. But when you look closely, identifiable patterns exist on how they ran their campaigns, with a few important differences.

First off, it’s a boy’s club. There are no women on the list. While Latin America is now familiar with women running for and winning higher office, none has risen to head the executive branch as an outsider. One possible exception is Violeta Chamorro, president of Nicaragua from 1990 to 1997. I personally don’t consider her a true outsider because she was the widow of a famous politician, served nine months in the pre-revolutionary government-in-exile and then in the first post-revolutionary junta, followed by a career running the leading opposition political newspaper. She was, therefore, a high-profile political actor when she ran for the presidency and, in my book, this disqualifies her as an outsider. Others, however, do include her because she had never run for office prior to becoming president. But even if Chamorro is included as an outsider, the number of women is still small. It could very well be that this privilege of running with little political experience is accorded mostly to machos. Big boastful machos. Trump: checked.

There is something democratic about the triumph of a newcomer. Outsiders in Latin America often mobilize voters who feel unrepresented and apathetic, victims of representation gaps more so than economic ones. Trump: checked. As political scientist Francis Fukuyama has argued, Trump mobilized sectors left behind by both the Republican and Democratic parties: less educated, mostly rural whites, along with some self-declared independents. In addition, outsiders often succeed in dislodging establishment figures. This too could be considered a democratic triumph – an opening in the straitjacket that established politicians impose on the entry of new personalities.

Few outsiders are entirely outsiders. Despite their claims to being unconnected to the status quo, most successful outsiders have some real connection to a country’s prominent institutions. Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, Ecuador’s Lucio Gutiérrez, Peru’s Ollanta Humala, and Guatemala’s Jimmy Morales had deep ties to the military. Jean-Bertrande Aristide in Haiti and Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, both former priests, and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, a former lay missionary, had deep ties to the Catholic Church. Haiti’s Michel Martelly was a popular singer, famous for dropping his pants on stage, and so had connection to the media world. Likewise, Alberto Fujimori (Peru), Abel Pacheco (Costa Rica), Antonio Saca (El Salvador), Mauricio Funes (El Salvador) and Jimmy Morales (Guatemala) were big TV personalities prior to running, as was Trump. Still others had ties to the business world as financial elites: Horacio Cartes (Paraguay), Saca again, and, of course, Trump. Thus, many newcomers usually owe their rise to pre-existing connections with the upper echelons of power. They are pseudo-outsiders, using the levers of the system to propel themselves to prominence. They often have some celebrity status, just not in politics. As a result, outsiders often spend energy on the campaign trail hiding parts of their resume, trying to keep up the appearance of their “outsiderness.” This helps explain why we got no tax details from Trump.

Outsiders have a higher chance of winning if they compete against politicians who are emblematic of the status quo. This is perhaps the most important point. In Latin America, when newcomers compete with highly traditional political figures, they thrive. Evo Morales (Bolivia), Morales in Guatemala, Pacheco, Chávez, Martelly, Correa, and Humala rose to prominence in political systems where presidential races were dominated by former presidents or their relatives. One could even argue that the appearance of very established politicians in electoral races propels the rise of (i.e., the demand for) outsiders. Thus we shouldn’t be too shocked that Trump’s two most important political accomplishments in 2016 (becoming the Republican Party nominee, and then president-elect of the U.S.) were facilitated by the fact that, in each race, he faced almost archetypically establishment figures who were, in fact, relatives of ex-presidents: Jeb Bush in the primary, and then Hillary Clinton.

To defeat established politicians, newcomers often engage in character assassination. One reason that Trump relied so much on insults during the campaign is that for outsiders to win, establishment politicians – and the establishment itself – need to be taken off their pedestals. From the left, Correa, for example, referred to Congress as the country’s sewer, and the parties as the country’s mafia. From the right, Morales (Guatemala) made a career as a humorist, often targeting politicians and calling for less tolerance for crime. Many of the derogatory slogans bandied about at Trump campaign events speak to that idea. The newcomer needs not just to defeat, but to obliterate the establishment. Outsiders thus become excessive iconoclasts, and this can make them excessive insult-makers. Trump went further than most (if not all) his Latin American coutnerparts by personalizing so many insults. But the key point is that they all rely on belligerent rhetoric. This is risky. Too much negativity may generate negative reactions, as was the case with Humala in Peru in 2006, whose belligerent rhetoric and close association to Venezuela’s Chávez cost him the presidency (to Alan García, a former president). For voters who are uninterested in outsiders, this reeks of desperation and inappropriateness. But there is a logic incentivizing outsiders to overplay negativity: for those craving big change, fault-finding can strike a chord.

Outsiders have a complicated relation with political parties. Some outsiders run by rejecting existing parties (Chávez, Correa, Morales in Guatemala). Others run by trying to hijack an existing party (Pacheco, Cartes, Funes). Both situations produce heightened animosity between candidate and party. This is important because it affects post-victory politics. In the case of party-independent outsiders, victory means facing an entire party system turned against them after victory, and this makes governance hard. In the case of the party-hijacking outsiders, the situation is different. The hijacked party can potentially become obsequious. Those in the party who challenged the newcomer during the campaign will approach the new Sun King begging for forgiveness for not seeing the light. The party becomes a facilitator of governance, not an obstacle. That means that if the outsider is interested in regime change, and not just policy change, the party will oblige. Trump is the latter case. He ran not as an independent, but as a newcomer who took over an existing party. This produced expected rejection from large parts of the Republican leadership. Now that he has won, those Republican leaders who criticized the newcomer are the party’s new pariahs. They must atone to their president-elect. This gives Trump remarkable powers. We should not be surprised to see the Republican Party giving Trump one of the longest, most generous honeymoons in recent U.S. history.

Trump’s uniqueness. Despite all these commonalities, there are two major differences about Trump’s rise in relation to outsiders in Latin America, and they have to do with Trump’s insult-propensity and electoral appeal.

Trump insulted not just establishment figures, but also vulnerable groups: minorities, immigrants, welfare recipients, victims of police brutality, people whose careers have tanked, veterans, parents of fallen of veterans, people with disabilities, women. Most of the time, his insults were direct and repetitive. Other times, they were indirect, as when he picked Indiana Governor Mike Pence as his running mate, perhaps one of the most anti-LGBT choices available. When Trump was viciously attacking Clinton, we were never quite sure whether he was attacking her for being an elite figure, or simply for being a woman. In Latin America, few successful newcomers run their campaigns insulting this many vulnerable groups. Some have leveled insults at the LGBT community during their campaigns (Cartes, Morales in Guatemala), but that’s about it. If anything, Latin American newcomers tend to exaggerate their commitment to the downtrodden. Trump instead made denigration of the weak, not just of the powerful, a trademark. This allowed him to mobilize non-minorities in some key states, but it also explains Trump’s second important difference with other outsiders: his electorally weak victory.

Trump’s electoral weakness is especially acute when compared to Latin America’s outsiders: when they win, Latin American outsiders do so by large margins – an average of 13 percentage points above their main rival. Some actually achieve 16 points or higher: Chávez, Fujimori, Saca, Morales in Guatemala. By a quirk of the U.S. electoral system, Trump will actually end up losing the popular vote by around 1 percent nationally. This electoral weakness will be a significant detriment, at least at first, and an important reason why he will still need the Republican Party to support him once in office. He will need his party a bit more than is the case with most outsiders in the region.

For years to come, we will debate whether Trump’s supporters voted for him because he ran against the establishment (the outsider hypothesis) or because of the nativist, exclusionary sentiments his campaign evoked (the nativist-populist hypothesis). What is already clear is that the “anti-weak” aspect of his candidacy was distinctive. This aspect far offsets any democratic gains he might have made by breaking establishment rules and mobilizing heretofore apathetic voters. Trump has likely alienated more than he has attracted. Some fear that, once in office, Trump may be interested in regime change, not just policy change, and that he will want to change the system to concentrate more powers in the presidency and quash dissent. Judging by the way he ran his campaign, it seems that he has already begun to move in that direction.

—

Corrales is professor of political science at Amherst College and member of the editorial board of Americas Quarterly. The second edition of his co-authored book Dragon in the Tropics: Venezuela and the Legacy of Hugo Chávez came out in April 2015.