Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world. Colombia, Brazil and Mexico rank as three of the world’s four most unequal countries. And in Colombia, according to The Economist, the top-income quintile earns 25 times that of the lowest quintile.

Social policies promoted by the state may be the principal vehicle for neutralizing this problem.

But the recent global economic crisis has challenged the response capacity of public agencies, increased demand for assistance and affected personal economic conditions across Latin America. In the Colombian context, the economic crisis was not as severe as in other countries. Still, the economic contraction plus recent reforms promoting the reparation of armed conflict victims; assistance to populations affected by recent floods; and making fiscal sustainability a constitutional principle have all put pressure on the state’s ability to respond.

To overcome these pressures, new sources of income are needed. Taxation is often noted as an answer, but it is also generally receives some resistance. So AmericasBarometer asked: who would be willing to pay more taxes to fund social assistance programs? This is not a new issue for Colombians. Individuals’ willingness to pay additional taxes was tested when in 2002 Bogotá Mayor Antanas Mockus promoted a voluntary additional 10 percent property tax, receiving the compliance of about 63,000 taxpayers.

The AmericasBarometer national survey of Colombia offers new insight into the characteristics of those who would be willing to “pay more taxes if they were used to give more to those in need.” Overall, 27 percent of respondents said they would pay more taxes in this case. Looking in more detail, the wealthier and the more educated (and to a limited extent, those who are male and under 51 years of age) express greater willingness to pay additional taxes for the sake of improving economic equity.

But beyond these characteristics, what matters most is the belief that the state should play an important role in the economy and in providing social assistance. Those who believe the state should intervene in the economy and guarantee social welfare express greater willingness to contribute; they tend to put their money where their ideology lies, so to speak.

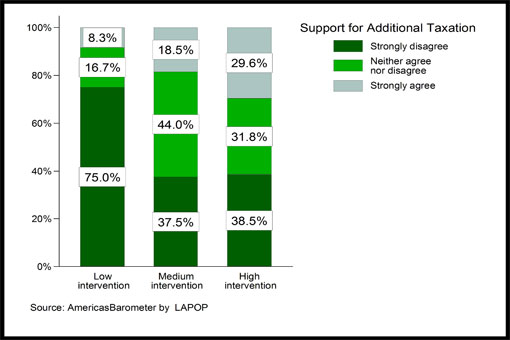

But opposition to new taxation is quite high (75 percent of respondents) among those who believe the state should have a limited role in the economy and in promoting social welfare. [see figure] In contrast, among those believing that the state should intervene in economic affairs (the “high intervention” column), almost 30 percent strongly favor paying additional taxes to help the poor.

It is important to note that many Colombians, both rich and poor, believe it is the state’s duty to promote social welfare, and, as well, that even among those with low levels of income, we find a significant number of individuals who express a willingness to pay additional taxes to support the neediest.

This is good news from the perspective of increasing state capacity to address income inequality; it suggests that support for additional taxation can be widespread across income levels. However, at the same time, what analyses of the data reveal is that being supportive of paying additional taxes to help the poor is highly sensitive to individuals’ personal economic situations. This is not to say their absolute income or wealth, but whether they perceive that they are able to afford additional expenses. Illustrating this finding, it is interesting to note that an increase in the property tax during 2003 and 2004 had the effect of deterring voluntary contributions in Bogotá.

Having both the means and the motives to pay for redistribution is not an easy set of conditions to satisfy. This may make it difficult for states to address inequality in the long run. Scholarship has identified numerous negative effects of poverty and inequality, including low levels of political engagement, social trust and conflict, and disparities in democratic attitudes and tolerance.

What the case of Colombia shows is that the pathway toward greater equality hinges on promoting both adequate economic conditions and positive perceptions of states’ participation in economic affairs. This is a dual challenge that must be dealt with for bringing hope and opportunities to those in the hemisphere that need it most.

This Web Exclusive is adapted from an article published by the same author in the Insights Series. The full article is available at the Insights Series website. The Insights Series is co-edited by Mitchell A. Seligson, Amy Erica Smith, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister with administrative, technical and intellectual support from the LAPOP group at Vanderbilt. The opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the sponsoring organizations.

Funding for the AmericasBarometer has mainly come from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Important sources of additional support were also the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and Vanderbilt University.