Special Section

A closer look at the leading candidates

in this year’s presidential elections

in this year’s presidential elections

* Not expected to be democratic

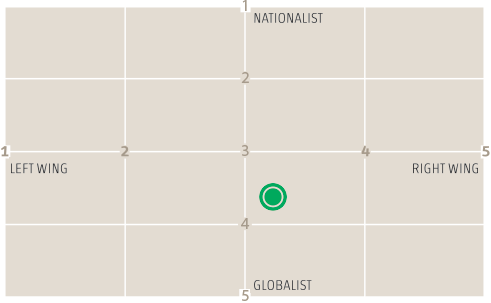

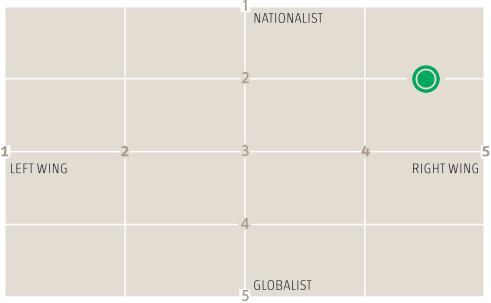

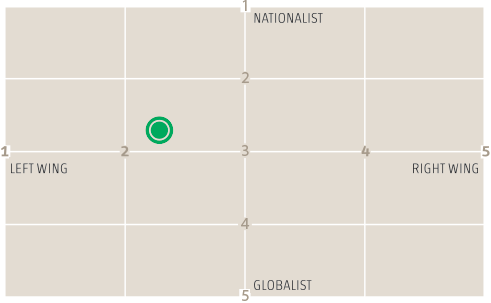

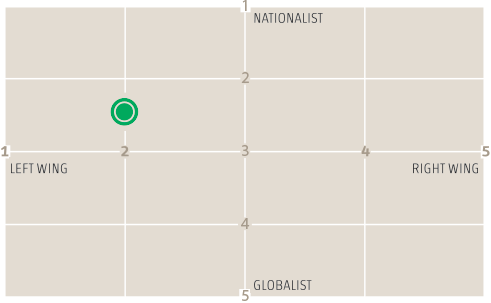

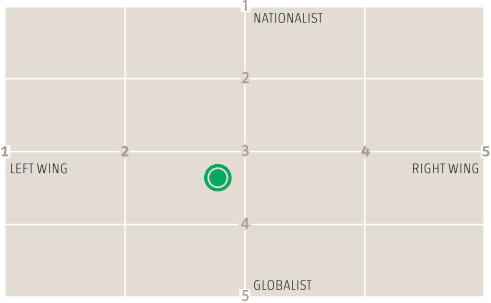

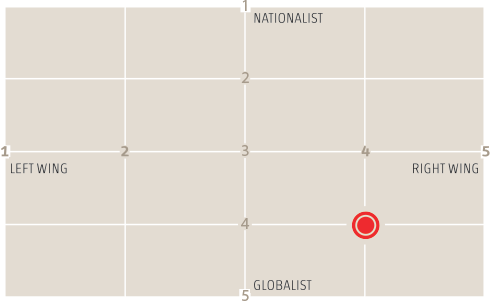

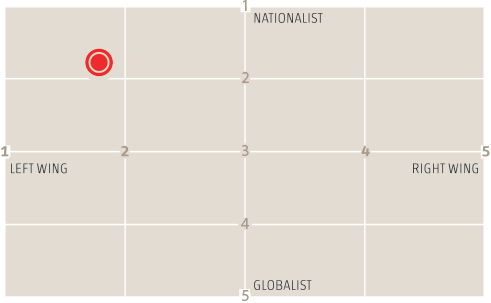

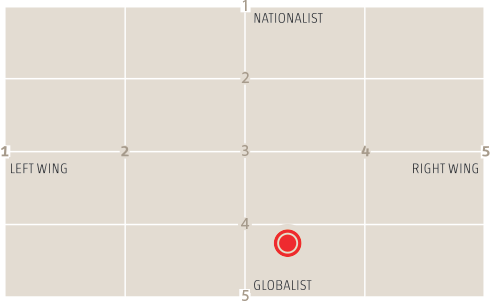

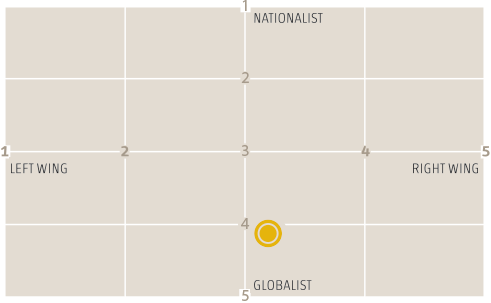

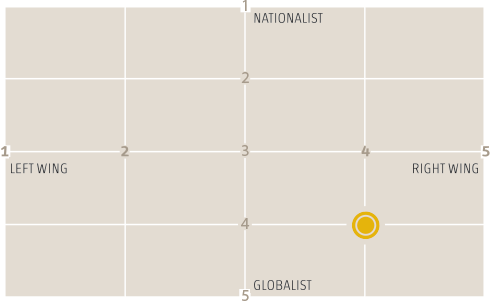

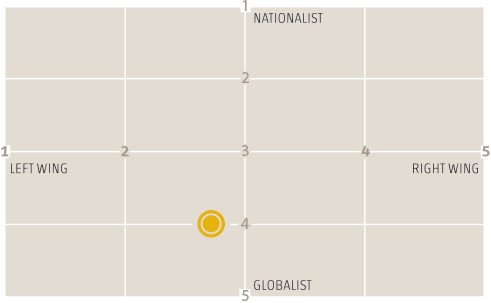

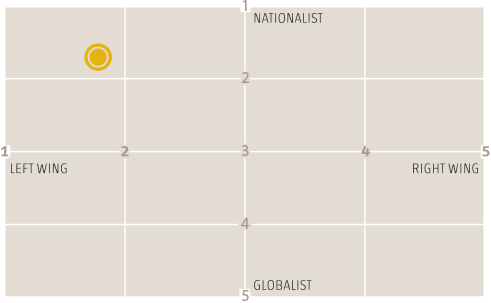

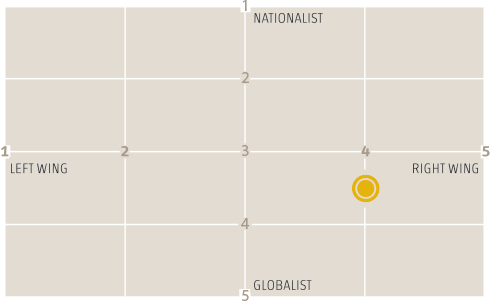

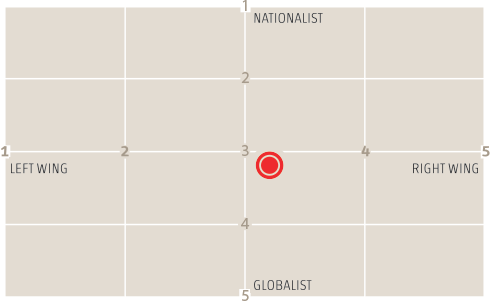

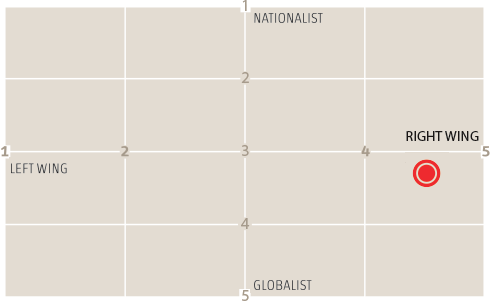

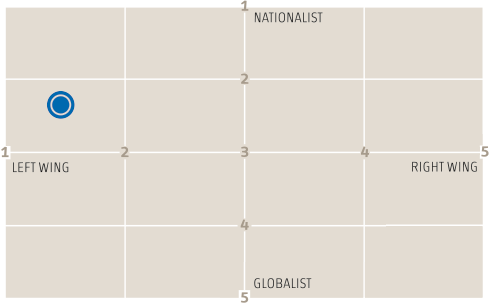

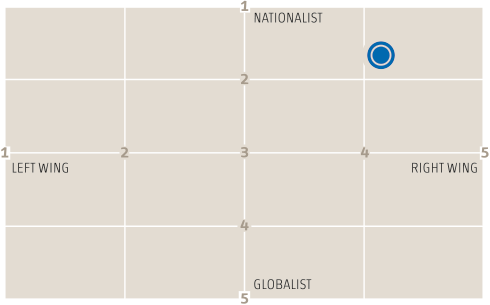

IDEOLOGY AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Brazil | October 7

Geraldo Alckmin 65, governor Brazilian Social Democracy Party“Lula wants to return to the scene of the crime.”How he got hereAlckmin began his career as a doctor, but has spent most of the last 17 years as governor of São Paulo, which accounts for a quarter of Brazil’s population and a third of its economy. His calling card, an 80 percent decline in the state’s homicide rate since he first took office, may resonate amid a national crime wave.Why he might winHe’s an affable, somewhat bland figure who doesn’t inspire the kind of hatred (or love) most other Brazilian politicians do. If the economy is humming by October 2018 and enough voters want the status quo, he’d be a safe pick.Why he might loseHe’s the leading establishment candidate in what still looks like a “Throw the bums out” election. Among leading candidates, Alckmin would fare worst against Lula in a runoff, according to a December poll. His low-key personality doesn’t play well outside the wealthier southeast.Who supports himResidents of São Paulo, business leaders, the “anybody but Lula” crowd for whom Bolsonaro is too extreme.What he would doNear-total continuation of President Michel Temer’s pro-business policies, with moderate to good support in Congress. Don’t expect a major reform or trade push, but a gradual attempt to shrink the state, streamline taxes and privatize.

|

Jair Bolsonaro 62, congressman Progressive Party“Brazil above everything, God above everyone.”How he got hereA retired army captain and a congressman since 1991, Bolsonaro’s popularity abruptly soared during the 2014–2016 recession as Brazilians lashed out against corruption, rising crime and the existing establishment. His statements in favor of military rule, torture, and the right to bear arms, and against minorities and democratic convention, have endeared him to critics of political correctness.Why he might winHis extreme law-and-order message carries tremendous appeal in a country with 19 of the world’s 50 most violent cities. He is one of just a few Brazilian politicians not facing corruption accusations. Avid, massive social media following.Why he might loseBrazil has a reputation, at least, as a tolerant, democratic country. Also, business leaders are skeptical of his self-proclaimed conversion to market economics, and in a runoff would surely prefer Alckmin.Who supports himBolsonaro is the leading candidate among Brazil’s wealthiest, best-educated voters, who are generally angriest about crime and corruption. Younger Brazilians, especially those age 18 to 25, are most likely to support him.What he would doHe might try to concentrate power in the executive branch, but has no significant party support and might struggle to govern. After espousing a nationalist, protectionist agenda most of his career, Bolsonaro has rebranded himself as a business-friendly, small-government conservative.

|

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva 72, former president Workers’ Party“In recent years, I have been the victim of a kind of massacre.”How he got hereWhat a journey it has been. Lula was president from 2003 to 2010, and left on top with a booming economy and approval near 90 percent. Then the economy crashed, the Car Wash scandal erupted, and his chosen successor was impeached. More recently, some Brazilians have concluded Lula’s alleged crimes were less severe than others’ — and are ready to tolerate his sins if he brings back the glory days.Why he might winLula has put his legendary charisma back to work, casting himself as a victim of political persecution by the Car Wash team. He can point to a robust record of poverty reduction and economic growth while president. He also has strong party support.Why he might loseHis legal troubles could bar him from being a candidate — and he might even be in jail by election day. Bears significant, if not primary, responsibility for one of the worst recessions in Brazilian history. His lead in the polls might vanish as less-known rivals gain name recognition.Who supports himThe poor, especially in Brazil’s northeast. But he has stronger support across social classes than many recognize.What he would doA question mark. Would he be the “Good Lula” of his first term (fiscal rigor, institution building) or the “Bad Lula” of his second (credit splurge, outlandish systemwide corruption)?

|

Ciro Gomes 60, former governor Democratic Labor Party“Brazil is living at the margin of the law.”How he got hereGomes casts himself as an anti-establishment outsider, but he has held numerous political offices, including finance minister, governor, mayor and congressman. Will probably be the standard-bearer of Brazil’s left if Lula’s legal troubles prevent him from being a candidate.Why he might winA strong endorsement from Lula would make him an instant favorite to reach the runoff. Combines an interventionist economic platform with an uncompromising anti-corruption message. Has a decent power base and name recognition in the poorer northeast.Why he might loseHis brainy, university lecture-style speeches go over a lot of Brazilians’ heads. It’s also not a slam dunk that Lula would endorse him; other possibilities include Fernando Haddad, the former São Paulo mayor, or former Bahia Governor Jacques Wagner.Who supports himLeftists, including those angry with the Workers’ Party. Older, better educated voters.What he would doUnrestrained by political convention or major donors, some observers believe Gomes would have the most radical economic platform in the race.

|

Marina Silva59, former senator and minister Sustainability Network“I can’t win an election with a lie.”How she got hereEscaped poverty, malaria and mercury poisoning growing up in the Amazon, learned how to read at 16, and transformed herself from a maid into a globally renowned environmentalist. Silva has run for president twice before, gathering about 20 percent of votes and missing out on the runoff both times.Why she might winHas one of Brazil’s most inspiring life stories. Her anti-corruption, anti-establishment message fits the moment. Combines social concern with a centrist economic platform.Why she might loseEven her biggest fans wonder if she has the physical stamina and coalition-building chops to be president. Staunch anti-Lula voters will never forgive her for serving in his government. Others feel her time has simply passed.Who supports her“Green” voters, business-friendly leftists, residents of medium cities and the lower-middle class. Her national name recognition trails only Lula’s.What she would doIt’s unclear she could accomplish much with Congress, given her miniscule political party and embrace of principle over Brasília’s pork-barrel politics.

|

Mystery Outsider“You can be a rank insider as well as a rank outsider.” – Robert FrostHow he/she got hereYes, there may still be room in this race for another candidate from outside the traditional world of politics. TV show host Luciano Huck ruled out a run in December, but some friends say he could still change his mind. Former Supreme Court Justice Joaquim Barbosa, who oversaw proceedings on graft in Lula’s government during the 2000s, could catch fire with an anti-corruption platform.Why he/she might winAfter years of recession and scandal, approval of traditional politicians has never been lower; one poll in December gave Congress just a 5 percent approval rating. Some believe candidates could enter the race as late as April.Why he/she might loseIf there were a “savior” capable of running away with this race, he or she probably would have done so by now. Brazilians still remember how they elected a charismatic outsider as president in 1989. Fernando Collor de Mello froze bank deposits, tanked the economy and was ultimately impeached. Many angry voters will probably just spoil their ballots or not vote at all.Who supports him/herTo be determined.What he/she would doWorth watching closely. Huck espouses a pro-business agenda, while Barbosa is a total wild card.

|

Mexico | July 1

Ricardo Anaya38, former party president National Action Party“The PRI is desperate … and it’s trying to divide the PAN.”How he got hereThis “boy wonder” got his political start at 21, when he ran for the state legislature in Querétaro. Now 38, he resigned his leadership of the National Action Party (PAN), to run for president with Forward for Mexico (Por México al Frente), an ideologically diverse coalition of opposition parties.Why he might winHe’s a talented political strategist. Under his leadership, the PAN won big in the 2016 midterm elections, snagging seven of the 12 gubernatorial seats that were up for grabs, including in states considered PRI strongholds.Why he might loseHe has lost potential allies and stands accused of damaging his party on the road to the top. Zavala’s departure from the PAN, in particular, will cost the coalition. Voters may be wary of his Machiavellian reputation.Who supports himPAN voters are generally middle class, well-educated, and most concerned about crime. Heading the coalition will force Anaya to court left-leaning voters from the Democratic Revolutionary Party and Citizens’ Movement.What he would doA proposed universal basic income was one of the coalition’s first specific policies, although it could amount to as little as $540 a year. It’s unclear how the coalition will square differing views on social policy.

|

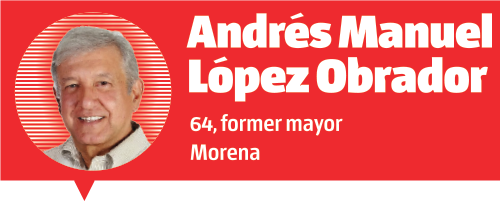

Andrés Manuel López Obrador64, former mayor Morena“We’re not against businessmen … we’re against corrupt politicians.”How he got hereWill it be a third strike, or third time’s the charm for López Obrador? The populist former mayor of Mexico City, known colloquially as AMLO, narrowly lost presidential votes in 2006 and 2012. He is once again a front-runner heading into 2018 — and he says this election will be his last.Why he might winLópez Obrador has name recognition, and his long-running critique of the “mafia of power” should play well, given the anti-establishment mood. Roughly 80 percent of Mexicans see corruption as a major problem, and faith in public institutions is in steady decline.Why he might loseIt’s happened before — twice. AMLO’s undisciplined rhetoric on the campaign trail has cost him votes. He drew criticism in December when, speaking in the violence- ridden state of Guerrero, he said he would consider amnesty for cartel leaders. Many of Mexico’s political and business elites are against him.Who supports himHe does best with young, middle class, and well-off voters, particularly in the capital and his home state of Tabasco. His backers are tired of the status quo of lousy jobs and poor wages — and ready to try something different.What he would doAMLO has vowed to sell the presidential plane and cut ex-presidents’ pensions. He toned down rhetoric against the 2013 energy reform, saying he’ll evaluate rather than overturn it. Critics compare him to Hugo Chávez, but an opposition-controlled Congress might limit his more radical impulses.

|

José Antonio Meade48, former minister Institutional Revolutionary Party“The country owes a great deal to the PRI.”How he got hereMexicans are tired of corruption, and no party is perceived as more corrupt than the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). One way to blunt that criticism is by running a candidate who isn’t a card-carrying member of the party. Meade — a technocrat who has served in both PAN and PRI governments — fits the bill.Why he might winHe’s widely viewed as a capable administrator, and has held several top secretariat posts: foreign affairs, finance, social development, and energy. He’s never been elected to office, but he’ll have the country’s biggest, most effective political machine behind him.Why he might loseMeade isn’t a household name. He has never run for office, and many voters say they won’t vote for the PRI regardless of the candidate.Who supports himMany of Mexico’s political and business elites consider Meade to be the best candidate for the job. He could steal votes from the PAN, particularly among its more religious members (Meade is a devout Catholic). The country’s first PAN president, Vicente Fox, backs him.What he would doA vocal supporter of the reform agenda set out early in the Enrique Peña Nieto administration, he’d likely continue to open industry to competition and invite foreign investment in energy, telecommunications and other sectors. He also backs special economic zones as a way to develop the country’s poorer regions.

|

Margarita Zavala 50, former first lady Independent“When I become president, I will make the decisions having to do with my government. No one else.”How she got hereThe lawyer, women’s advocate and former first lady to Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) quit the PAN in October after 30 years as a member, claiming that party president Ricardo Anaya had denied her any opportunity at becoming its nominee. She’s running as an independent.Why she might winZavala proved her ability to connect with voters in her time as first lady. She surpassed her husband’s popularity in the PAN, and still has the support of the party’s Calderonista faction. She’s a well-known national figure, and could be a major beneficiary if Anaya’s coalition is unable to hold together.Why she might loseHer husband started Mexico’s drug war, which may haunt her on the campaign trail — particularly as Mexico in 2017 experienced some of the highest homicide rates in its recent history. Zavala has never had to win a popular election (she became legislator on a party list) and it will be hard for her to break through without traditional party machinery.Who supports herAside from the Calderón nostalgia vote, Zavala has more centrist and women supporters than most PAN politicians. She also does relatively well with young voters. What she would do She says violence and crime in Mexico persist because Peña Nieto “abandoned” the task of strengthening institutions after the drug war. She tends toward traditional PAN social views — including in her personal opposition to abortion.

|

colombia | May 27

Humberto de la Calle71, former minister Liberal Party“We need the young people to put an end to hatred.”How he got hereThe elder statesman of the race, De la Calle has spent more than three decades in public life as a minister, a primary presidential candidate, and as vice president to former President Ernesto Samper (with whom he later had a falling out). In 2012 President Juan Manuel Santos tapped him to lead peace negotiations with the farc, and in November he was chosen as the Liberal Party’s candidate for 2018.Why he might winHe’s a good-natured centrist in a race that is sure to feature extreme — and off-putting — rhetoric. He knows the peace deal backwards and forwards, and is widely viewed as the candidate best placed to oversee its implementation.Why he might loseThe peace deal. About half of the country opposed Santos’ agreement with the farc, and no candidate is more tarnished by association (with it and with Santos) than De la Calle. Others candidates, particularly Fajardo, will offer strong competition for Colombia’s centrist vote.Who supports himThe Liberal Party was long a dominant force in Colombian politics and is still the second-largest party in Congress. Preserving the peace deal is a top priority for many voters.What would he doHe has said that implementing the peace deal is the most important task facing Colombia’s next president, but is also focused on reducing inequality and tackling Colombia’s competitiveness gap.

|

Iván Duque41, senator Democratic Center“Diplomatic euphoria doesn’t guarantee the construction of peace.”How he got hereHe’s the son of a former governor, and served stints at the UN and the Inter-American Development Bank. Still just 41, he’s a rising star of the Democratic Center party, beating out four other “pre-candidates” for the right to carry the flag for former President Álvaro Uribe in 2018.Why he might winHe talks like a centrist and is less polarizing than other candidates who opposed the peace deal. His selection to lead the Democratic Center makes him an instant front-runner. Some may call for him to run as vice president in a conservative coalition, but given Uribe’s weight in national politics, that outcome seems unlikely.Why he might loseInexperience. He’s only been a senator for three years, spending much of his professional life in the sedate halls of U.S. universities and international institutions. Colombian politics get messy, and he’ll have to distinguish himself from other front-runners, like Vargas Lleras.Who supports himUribe supporters and much of the “no” camp from the peace deal. If he runs an ideas-based campaign, and stays out of the mud, he could even sway some young independents.What would he doDuque has been critical of Santos’ economic policy, particularly a development plan that shifted focus away from infrastructure, mining and agricultural development. As with other pro-Uribe candidates, he wants to revisit or revise some parts of the FARC deal.

|

Sergio Fajardo61, former governor Citizens Commitment“If courage (in the form of insults) is what people are looking for, that’s not me, because that’s not the kind of courage that Colombia needs.”How he got hereA former math teacher and newspaper columnist, Fajardo didn’t enter politics until well into his 40s. As mayor of Medellín, he oversaw a big reduction in violence and carried out an ambitious — and internationally lauded — public works plan. From 2012 to 2016, he was governor of Antioquia, Colombia’s second most populous state. He’s now near the top of early polls, and will lead the “neither Santos, nor Uribe” coalition in 2018.Why he might winSeen as a clean, competent politician without strong ties to traditional power elites, Fajardo should find broad support among Colombians looking to reform — but not upend — the political hierarchy.Why he might loseDespite enduring popularity in Antioquia, Fajardo is still not well-known at the national level. His opponents will take the opportunity to paint him with a broad “leftist” brush that includes more radical figures — some on Twitter call him “FARCjardo.”Who supports himSome of his hometown crowd in Antioquia (which he’ll have to split with Uribe’s Democratic Center) and a large chunk of urban and educated voters.What would he doMiddle-of-the-road economics, a push for transparency and a focus on improving education. Implementing the peace deal would be a priority — but not the driving force behind his government.

|

Gustavo Petro57, former mayor Progressive Movement“The more I am attacked, the more support I get.”How he got hereA former member of the left-wing M-19 rebel group, Petro played a role in its disarmament in the 1980s and the rewriting of the Colombian constitution in 1991. As a congressman he railed against corruption and the political elite, and came in fourth in the presidential race in 2010. Petro cemented his standing as a national figure with a controversial turn as mayor of Bogotá starting in 2011.Why he might winHe’s an articulate populist and a charismatic anti-establishment candidate at a time when Colombians’ faith in public institutions is near an all-time low.Why he might loseColombia’s two-round presidential system should put a damper on Petro’s presidential ambitions. Winning head-to-head against a more mainstream opponent would require him to connect with voters well beyond his base — which he has not done so far.Who supports himLower-income voters across the country, who see him as their only real champion, as well as some young urban voters who are disenchanted with politics — and not put off by his guerrilla past.What would he doAs mayor, Petro proved himself more a man of ideas than of execution; a poorly managed public takeover of Bogotá’s trash collection system led to his ouster. He advocates for agrarian reform, renewable energy, and social programs that favor Colombia’s marginalized classes.

|

Marta Lucía Ramírez63, former defense minister Independent/Conservative Party“The FARC’s interest has been, and continues to be, to seize power.”How she got hereNo one can doubt Ramírez’s presidential bona fides. She was the country’s first — and still only — woman to serve as defense minister (under Álvaro Uribe). She’s also been trade minister, Colombia’s ambassador to France, and served in the Senate. In 2014 she earned more than 15 percent of the vote running on the Conservative ticket. Now an independent, she’s currently in coalition talks with the Democratic Center.Why she might winShe has a positive relationship with two influential ex-presidents (Andrés Pastrana and Uribe), and if she found herself leading a coalition with other conservative forces — namely the Democratic Center — could quickly become a front-runner.WHY sHE MIGHT LOSEThe Democratic Center’s candidate (Duque) is most likely to lead any conservative coalition into the first round; Ramírez may have to resign herself to the vice presidency or a cabinet post.WHO SUPPORTS herShe split from the Conservative Party but will still attract voters from the traditional center-right; she is more well-known — and viewed more favorably — than most other conservative candidates. There are plenty of Colombians who think it’s time the country had a woman president.What would she doShe would seek a referendum on changes to the peace deal, particularly on points related to transitional justice. Like most of Colombia’s presidential hopefuls, she would look to make business-friendly reforms to the tax code, widen the tax base, and pursue foreign investment.

|

Germán Vargas Lleras55, former vice president Radical Change“I consider myself a man of the center … except when it comes to security.”How he got herePolitics are in his blood. Vargas Lleras is the grandson of a former president and related to another. He was a minister and then vice president under Santos, though he won’t have the president’s support in 2018. Vargas Lleras resigned in March to pursue what will be his second run at the presidency.Why he might winElectoral machinery and political savvy. He avoided coming down too far on either side of the peace debate, and has a reputation for getting things done. He’s a safe vote for business and establishment voters who aren’t defined by their support or opposition to the peace deal.Why he might loseHe’s well-known and near the top of the polls, but that doesn’t mean he’s popular: Nearly 60 percent of Colombians have an unfavorable view of him, according to Gallup. More than most, his Radical Change party is under the microscope for corruption.Who supports himHe has a strong base of support on the populous Caribbean coast and is well-liked by the business elite. Vargas Lleras and “the one Uribe chooses” will battle it out for Colombia’s center-right.What would he doPro-growth, pro-business economics. He wants to make it easier for foreign firms to invest, focusing efforts on infrastructure and mining. He also hopes to streamline the country’s bureaucratic health care system.

|

Paraguay | APRIL 22

Efraín Alegre55, former senator Authentic Radical Liberal Party“Paraguay doesn’t deserve this moment, to have a president who has made the country anxious for six months.”How he got hereA former national deputy and senator, Efraín Alegre served as public works and communications minister under President Fernando Lugo from 2008 to 2011, and now leads the center-right opposition Authentic Radical Liberal Party. This is his second run for president; in 2013 he was the chief opponent to President Horacio Cartes.Why he might winHe’s the most important member of the chief opposition party, and he’s up against a governing party whose president has the approval of only 1 in 5 Paraguayans.Why he might loseAlegre’s biggest challenge will be a lack of charisma. Some also see him as a weak candidate, a perception bolstered by his loss in 2013. Together, these will make it difficult for Alegre to attract the independent vote, which will be paramount to winning in April.Who supports himOpponents of re-election and some leftist groups, thanks to his party’s alliance with the leftist Guasú Front, which is supplying Alegre’s running mate.What he would doAlegre led the opposition to Cartes’ 2017 effort to change the constitution to allow for presidential re-election; a win in April would settle the matter for now. He has also called for doubling the number of police in the streets to tackle crime, and for a national constituent convention to reform the judiciary.

|

Mario Abdo Benítez46, senator Colorado Party“History must be analyzed in a dispassionate way, and we can’t deny that Stroessner built a large part of Paraguay’s current infrastructure.”How he got hereThe son of former dictator Alfredo Stroessner’s private secretary, Abdo represents a dissident voice in the ruling Colorado Party. The owner of two construction companies, Marito, as he’s known, was elected senator in 2013 and president of the Senate in 2015.Why he might winThough he defeated President Horacio Cartes’ choice for the Colorado nomination in December, Abdo is still likely to have the party’s money and machinery working in his favor. He’ll also benefit from divisions on the left and a supportive media.Why he might loseVoting for a son of the dictatorship is simply not an option for many Paraguayans.Who supports himThe Colorado Party’s conservative base, which has distanced itself from Cartes. Soy farmers, whose support Abdo earned as a congressman by opposing taxes and regulations on the crop.What he would do: Abdo would continue Cartes’ focus on driving economic growth through trade and foreign investment, although he promised voters during the primary campaign that he would support state businesses. A staunch Catholic, Abdo opposes progressive social changes like the legalization of abortion and same-sex marriage.

|

costa rica | february 4

Carlos Alvarado38, former minister Citizens’ Action Party“We need a government of national unity that respects differences.”How he got hereAlvarado Quesada served as communications director for Guillermo Solís’ successful presidential campaign four years ago. That connection helped him land the role of human development minister and later labor minister. He earned 22 percent of the first-round vote.Why he might winIf he can steer the national conversation away from the social issues that dominated the first round, he has a shot. Though a ruling party candidate, he presents himself as a politician of change — a discourse he effectively used in 2014 to help Solís.Why he might loseAlvarado Quesada’s progressive social views will lose him conservative votes, especially given the culture war tenor of the election so far. He will also suffer if voters associate him with the ongoing cementazo scandal, an influence-peddling investigation touching members of the president’s inner circle.Who supports himAlvarado Quesada can expect support from young, urban middle-class sectors. A believer in the role of the state, he’s also best positioned to attract state employees.What he would doAlvarado Quesada campaigned against Costa Rica joining the Pacific Alliance and some believe he would pursue protectionist economic policies. As president he says he would maintain the country’s state-run oil and electricity monopolies and pursue job creation through public-private partnerships.

|

Fabricio Alvarado43, former congressman National Restoration Party“There’s nothing more progressive than defending life and the family.”How he got hereFew saw his rise coming. Less than two months before the first-round vote on Feb. 4, polls showed support for Alvarado Muñoz at around three percent. But on Jan. 9, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ruled that Costa Rica must recognize same-sex marriages and grant adoption rights to same-sex couples. Alvarado Muñoz, a contemporary Christian singer, promised fierce opposition to the ruling, galvanizing conservative voters and finishing first on Feb. 4 with a quarter of all votes cast.Why he might winTwo-thirds of Costa Ricans share Alvarado Muñoz’s opposition the IACHR ruling. He has also tapped into anti-establishment sentiment by equating progessive policies with an attack on traditional values by an elite political class.Why he might loseNoise surrounding the IACHR ruling may die down, and Alvarado Muñoz has yet to articulate a plan to tackle record-high levels of crime and an unemployment rate around 10 percent.7 lost him support within the party. Young voters are also put off by Álvarez’s increasingly conservative views, a result of his party’s recent alliance with evangelicals.Who supports himEvangelical Christian and conservative voters, and others who are frustrated with status quo politics.What he would doAlvarado Muñoz has so far focused on social issues and promised to pull Costa Rica from the IACHR. His economic views remain unclear, and thus, say analysts, could be malleable.

|

The Non-Democratic Elections

Cuba | April 19

Efraín Alegre55, former senator Authentic Radical Liberal Party“Let them say we censor (the media). It’s fine. Everyone censors.”Why it’s not democraticThe Communist Party has relaxed entrance rules for local elections, in theory. In practice there’s still only one game in town. One group of around 170 opposition candidates that attempted to register for municipal elections in 2017 was blocked from getting on the ballot entirely. The decision of who governs Cuba — let alone who will take over for Raúl Castro as president in 2018 — is not one for the voting booth.How he got hereAs first vice president, Díaz-Canel is constitutionally in line to take over for Castro, and he’s widely viewed as the favorite for the job. The 57-year-old started as a low-level civil servant and worked his way through the Communist Party ranks. The National Assembly will choose a new president in April, and Castro will stay on as leader of the party. But if all goes as expected, Díaz-Canel could soon be the most powerful man in Cuba.What he might doNot much was known about Díaz-Canel until 2017, when a video leaked in which he took a hard line against any democratic opening on the island. He suggested the government should disallow opposition candidates, maintain strict limits on private businesses, crack down on dissent, and keep the U.S. at arm’s length. Some wonder if the leak had more to do with political theater than with what Díaz-Canel really believes. Nevertheless, he shouldn’t be expected to reverse course on the policies that make Cuba what it is — especially not in the Trump era. |

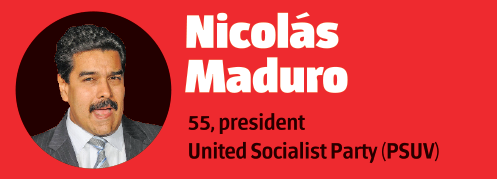

Venezuela | May 20

Mario Abdo Benítez46, senator Colorado Party“If anyone from the masses votes against Maduro, they’re voting against themselves.” ”Why IT’S NOT DEMOCRATICThe stifling of dissent under former President Hugo Chávez has only become more extreme under his successor. Maduro has shut down independent media, set security forces against protesters, and jailed opposition leaders on trumped-up charges. Regional elections in October were marked by polling place irregularities and last-minute rule changes that all but ensured a government victory. There is little reason to believe that presidential elections in 2018 — now set for May 20 — will be any better.How he got hereMaduro has survived criticism abroad and falling support at home by pampering the military and keeping hold of core Chavista voters with social programs and giveaways. The creation of a Constituent Assembly in July sapped the opposition-held National Assembly of its authority. Few believe the opposition MUD coalition can offer a meaningful check on Maduro’s authoritarian ambitions for now.What he might doRival factions within Chavismo aren’t likely to displace Maduro in 2018, but the long-term battle for control of the ruling PSUV isn’t over. The air of legitimacy afforded by an electoral victory would help Maduro further empower military allies while sidelining rival figures like Diosdado Cabello. His remaining priority will be to avoid outright default; this is no small task, but unless the opposition and international community can reassert pressure on the government, Maduro will be well positioned to keep control of Venezuela for the foreseeable future. |