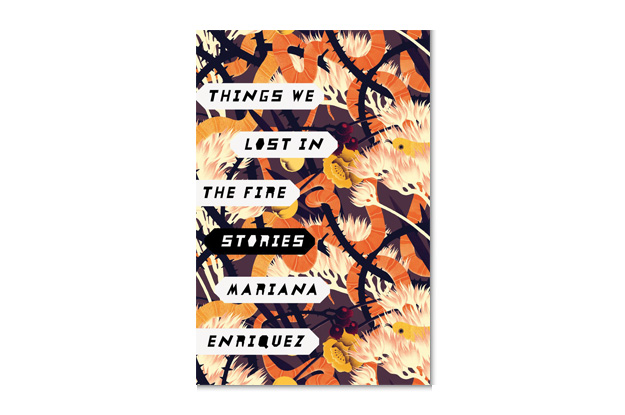

What terrifies more, the past or the present? The imaginary or the real? The supernatural or the self? Don’t answer. Not yet. Not until you’ve read Mariana Enríquez’s masterful, disturbing short story collection, Things We Lost in the Fire (Hogarth Press). Wait until you’ve traveled, eyes open, through her perilous terrain, where either/or categories are blurred and the real question involves the relationship of one terror to another.

Set in contemporary Argentina, each story, with a single, notable exception, is told from a female perspective. Each is unique, but thematically related. And each begins with a rather conventional hook: All is normal, relatively speaking, until X occurs. But get ready. Because X — a grimy handshake, a girl pulling fingernails off with her teeth, an amputee who coddles her stump — is anything but conventional. And things only get stranger from there.

Indeed, one could be lured into identifying these tales as horror stories, given the plethora of ghosts, witches and inhuman savagery they contain. But Enríquez dispels us of that idea with the intrusion of historical details, dates, events and names that push through the generic soil like resistant weeds: 1990, the Malvinas, Perón. Just when we believe in the monster, up pops the dictator.

Supernatural incidents occur also at the moment of personal epiphany: lesbian awakening, recognition of abuse, the sudden acknowledgement of guilt. That’s when the ghosts really strike, when it’s hard to tell which terror is more frightening: a tingling below the belly button from a young girl’s touch, or the pounding on windows by soldiers who aren’t really there.

On one level, such incidents are the bubbling up of the unconscious, a psychic fire in which characters sometimes gain more than they lose. But Enríquez won’t allow us to take full refuge in metaphor. Spirits may be representative of internal states, but as serial killers, dead children and, as in the title story, self-immolating women, they are also chillingly real.

Place is a central character here, and it too is a blend of the concrete and symbolic. Houses are more often prisons than havens, more evil than comforting. “Maybe the house didn’t let me talk,” says one of the characters. “Didn’t let me save them.” So too are cities living entities, embodiments of their inhabitants. Buenos Aires beckons with its bourgeois civility. But only in certain areas. Like the repeated power outages, degeneracy flickers everywhere else.

It is the “everywhere else,” life on the margins, that interests Enríquez most. The forgotten, the ugly, the disfigured. Cults and demons. They are inventions, but also suggestive of the actual victims of political inaction and class struggle; the human detritus of inequity. And her language and tone reflect their conditions: raw, brutal, flat, exhausted. Images of carrion, decay and rotting permeate the narratives, the stench rising from the pages. As a reader, you might turn away, hesitant to seek their source. But Enríquez provides it nonetheless — in homes devoid of love, in marriages of convenience, poverty, ignorance, unwanted children. It is the smell of history swept under the rug.

There is some unevenness in these stories, and at times the macabre descriptions seem gratuitous. Enríquez is in love with words, and that love periodically gets the better of her. But overall the collection speaks to our deepest, and darkest, concerns. Argentine and otherwise. There is little in these stories to soothe the savage beast. A moment of humor here and there (a skeleton companion, calavera, nicknamed Vera for short), and a few passages of uncompromised beauty. But these are fleeting. They stand out, like golden branches over a raging river. We can admire — but not count on them for safety.

—

Russell holds a Ph.D. in American literature and is the author most recently of Rule of Capture, an award-winning novel set in 1920s Los Angeles.