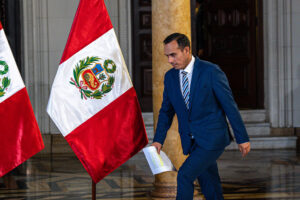

LIMA—On February 18, in a surprising maneuver, Peru’s Congress elected José María Balcázar to become the nation’s new president, following the removal of José Jerí a day before amid allegations of misconduct. These moves, just two months before the first round of the general elections, may well have been justified, but they confirm the political instability and deep fractures in Peruvian politics ahead of a pivotal moment.

Although his term will be brief and limited in scope, Balcázar, an 83-year-old former judge and member of the leftist Perú Libre party, faces the tough challenge of guiding the country through what could be its most significant vote in recent years. Balcázar is a controversial figure who supports the age of consent being 14 years old. He was a judge in Lambayeque, a city north of Lima, and was removed from the judiciary for misconduct. He also faces several penal investigations, including one for allegedly negotiating his investigations with former Attorney General Patricia Benavides in exchange for his vote in support of her in Congress. He denies wrongdoing.

The fact that Balcázar is Peru’s ninth president in a decade highlights the instability of the moment and the increasing authority of Congress, which has turned Peru into a de facto parliamentary autocracy. How Congress exercises this power will be crucial in the years ahead.

With fierce opposition in Congress controlled by right-wing political parties—Fuerza Popular, under the leadership of Keiko Fujimori, and Renovación Popular, led by Rafael López Aliaga, both presidential candidates—the risk of implementing radical policies may be limited. Additionally, the new president will have only five months in office. However, he has said he would grant a presidential pardon to former President Pedro Castillo, who is in jail and sentenced for conspiracy to rebellion. He may also try to benefit Vladimir Cerrón, who is in hiding after the judiciary sanctioned him with preventive prison and is running for president with Balcázar’s Perú Libre party.

He faces the difficult task of leading the country through what may be its most consequential vote in recent years. Balcázar’s term will be brief, lasting only until the presidential election winner is inaugurated on July 28. However, it is apparent that to win the interim presidency, he negotiated with the two most cronyist political parties, Podemos Perú, led by José Luna, and Alianza para el Progreso, under the leadership of Cesar Acuña.

In his inauguration speech last night, Balcázar said he would ensure a smooth and transparent election process, strengthen democracy, fight crime, and support the economy. Crime is a key problem due to the rise in extortion and other violent offenses in major cities such as Lima and Trujillo. Another key task is to maintain the momentum of the economy, which grew at 3.4% last year, and ensure that investors’ expectations remain upbeat and that private investment flows, which may prove difficult for the leftist president.

A third challenge is the fiscal accounts. Although former Finance Minister Mirelles said she had met the 2.2% of GDP deficit target, the independent Fiscal Council said she had met only two of the four targets. Moreover, most of the expenses have been pushed into 2026, and while the government has a 1.8% deficit target, our forecasts call for 4.1% of GDP. Restraining public spending in an election year and by a leftist government may prove difficult. Finally, there is Petroperú, the state-owned oil company that has been put under reorganization. It is apparent that Balcázar may want to reverse this process and provide additional financing from the Treasury.

The latest ouster

The transition to the new government to be elected in April (and then possibly in a presidential runoff in June) will be complex, and Balcázar will need his best talent to fulfill the country’s expectations.

Jerí had a positive start, trying to emulate El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele in fighting crime, which appealed to the population at large. This was reflected in his high initial popularity. Unfortunately, his cronyism quickly emerged.

On December 26th at midnight, he was recorded entering a Chifa (a Chinese restaurant) to meet two Chinese entrepreneurs who had contracts with the state and had visited him many times when he was in Congress. One had submitted an extension request for a hydroelectric project awarded by the previous government but failed to start it. Moreover, both entrepreneurs were involved in illegal activities, one in mining, the other in timber. Both had been investigated by the Attorney General’s Office and deny wrongdoing. Then, the press reported a series of irregular after-hours meetings held in the president’s offices with young women, who later received contracts to work with the government. Jerí denies any wrongdoing.

Against this backdrop, the pressure to oust him mounted. Congress split in two—those who believed his sudden ouster could result in unacceptable instability, like the Fuerza Popular party of Keiko Fujimori, and those who found Jerí’s actions unethical and unacceptable.

But there were legal impediments to ousting him. The Congress was in recess and needed 78 votes to call an extraordinary session. Then the decision was made on which law applies—a Constitutional provision on impeachment, or a special law passed in 2001 for acting presidents who become presidents after being Congress’ speakers. For the former option, two-thirds of the votes of the attending members of Congress were needed, for the latter a simple majority. Ultimately, Congress opted for the latter and ousted Jeri with 75 votes.

Unlike what happened in 2018, when Congress invoked a constitutional escape clause, this time it opted for a simple law to dismiss Jerí. In 2018, former President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was impeached under a vague article of the Constitution that allows Congress to impeach the president with a two-thirds vote if he is “morally unfit to govern.” This sparked the political crisis that has led to Peru having 9 presidents in 10 years. This time, as in 2018, they tweaked legislation and used the law that best serves their purpose—in this case, one that requires only a simple majority. In both cases, by undermining the 1993 Constitution that is the true anchor of the political stability, Congress moved away from a rules-based liberal democracy and into a discretionary political system closer to parliamentary autocracy.

Institutional decay

In our view, this illustrates the institutional erosion Peru has experienced since 2016, when the leader of the majority in Congress, Keiko Fujimori, said, “We will govern from Congress.” Since then, Congress has ruled, ignoring the division of powers called for in the Constitution. Does this mean Peru has become a parliamentary democracy, similar to European nations? Not really. It means Congress has become an autocracy that appoints and removes presidents at will, ignoring the protections the Constitution affords presidents, precisely to ensure stability.

The upcoming presidential and congressional elections, which restore the Senate abolished in the 1993 Constitution, offer an opportunity to reinstate liberal democracy and the division of powers. The reinstatement of the Senate is a product of a 2024 electoral reform that also reversed a ban on consecutive terms for legislators.

Congress has become the country’s most unpopular institution, and several polls show respondents saying they would not vote for any political party in Congress. Once the Senate is seated, hopefully with more senior politicians, it will take responsibility for impeaching presidents. This might ensure that future presidents will have a better chance of completing their terms.