SÃO PAULO — Despite substantive efforts in recent years, racial gaps in Brazil remain significant. Last year, we published a book documenting the evolution of racial inequality in the country, touching on income, education, health, violence and political representation. Overall, things do not look great. Although there has been some progress in addressing racial disparities over the past few decades, it has reached only a small proportion of Black Brazilians. New public policies are needed to promote a more equal nation.

Brazil was long regarded as a “racial democracy”, and it took generations of scholars and decades of organized Black movements to debunk this myth. There has also been growth in racial consciousness in Brazil even in the past five years, with more people now identifying as Black. Today, most Brazilians recognize that racism prevents many from achieving their full potential, but to what extent has this recognition translated into improved well-being for Black Brazilians?

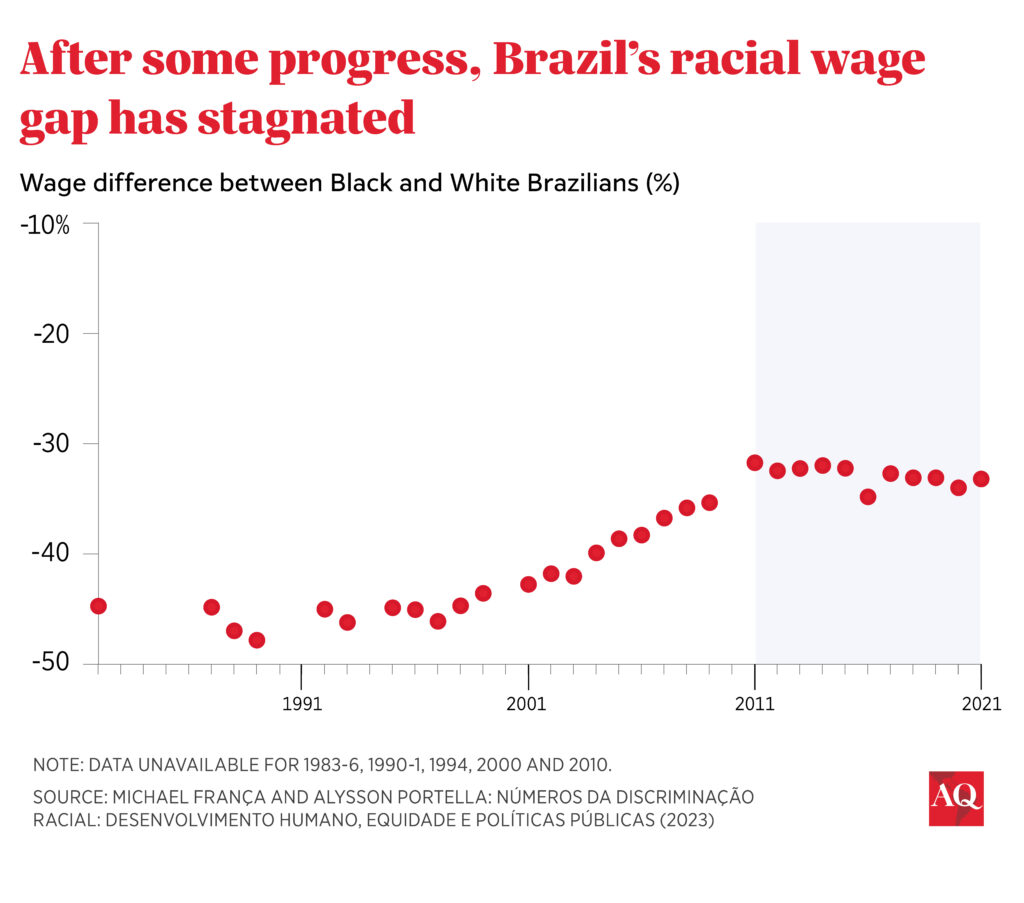

Long-term trends in racial inequality in earnings show a decline over the past forty years, but the gap has increased recently. In the 1980s and 1990s, Black workers received 44-48% less than White workers. In the late 1990s, the racial earnings gap started to narrow and was reduced to 32% by 2011. But since then, the wage gap has remained between 32 and 35%.

This reduction in earnings inequality was small and restricted to a short period around the 2000s. It was likely the result of other factors that contributed to an overall decrease in inequality—such as higher minimum wages and a reduction in wage differences between workers with high and low levels of education—rather than advances in racial equality itself.

Wage differences have remained pervasive, even when comparing workers with similar jobs and levels of education and experience. Considering these factors, Black workers received around 13% less than White workers in the 1980s. This gap has remained stable through 2020.

From this point of view, no progress was made at all. Despite overcoming a dictatorship, controlling hyperinflation, implementing conditional cash transfers, and introducing race-based affirmative action in universities, Brazil was unable to reduce discrimination in the labor market over the last forty years.

Still, there is a somewhat positive message. Most—but not all—racial differences are due to factors other than discrimination in the labor market. They include different types of employment, variations between different regions of Brazil, and, most importantly, different levels of educational attainment between Black and White Brazilians. This suggests a promising avenue for reducing labor inequality: promoting equality in education.

Targeting education

Congress recently renewed and updated its law guaranteeing affirmative action in public universities. The legislation, first enacted 12 years ago, reserves 50% of slots in these universities for students from poor families, and part of these slots are exclusively for Black and Indigenous students.

The law’s renewal in October 2023 assures that the country remains on the right track, but college access remains the main challenge. Brazil managed to ensure universal access to primary education for Black and White children alike during the 2000s. Although many teenagers are still not enrolled in high school, racial differences are decreasing fast.

In the 1980s, higher education was the prerogative of privileged Brazilians, most of whom were White. College enrollment has expanded quickly in Brazil since the late 1990s, with differing effects on racial equality.

On the one hand, if we look at the difference in enrollment rates, White Brazilians have fared better: In the early 1980s, their enrollment rates were 6 percentage points ahead of Black Brazilians. Today, the gap is 14 percentage points. On the other hand, the enrollment of Black Brazilians improved faster, rising from 2% to 16% (eight-fold), while for White Brazilians that rate went from 8% to 32% (four-fold). If trends continue like this, the difference in enrollment rates by race might narrow significantly in the coming decades.

However, two factors indicate that this trend might not last. First, affirmative action policies have limited reach. They apply only to public universities, which are among the best in Brazil, but represent less than a quarter of total enrollment nowadays.

Second, Black children are lagging behind White children in every measure of learning we have available. In every school grade, Black children perform worse overall, when compared with White children from a similar socioeconomic background, and even within the same school. Without fixing this problem, there is not much hope that racial gaps in university admissions and earnings will converge in the future.

Taking action

Solving racial inequality will require action across several fronts. First, research shows that learning gaps start before school and even before children are born. With lower levels of support for pregnant Black women and less stimulating home and preschool environments, Black children enter school at a disadvantage. Therefore, public policies must improve Black families’ access to health and childcare.

In school, racial discrimination further hampers Black children’s ability to develop. Teachers’ lower expectations, bullying, and how parents respond to negative racial stereotypes contribute to this scenario. To deal with these problems, schools must act on two fronts. First, they should implement color-blind programs that benefit mostly low-performing students, such as tutoring. Second, anti-racist teaching that gives students tools to confront racism must be an integral part of schools’ curricula.

Expanding affirmative actions in two ways might also help overcome two distinct problems. First, the government can design incentives for private colleges to reserve some slots for Black students, complementing current policies that cover only public universities. Benefits could include preferential access to subsidies, student loans and tax exemptions for institutions that comply with these rules. Second, the government can expand affirmative action to employment in private firms that take part in public procurement. This kind of regulation was successfully implemented in the U.S. in the past, and can be an important tool in fighting discrimination in the labor market.

Recognizing a problem is the first step towards solving it. Brazil has already debunked the myth of racial democracy, but there is still a long road ahead when it comes to designing efficient public policies to address racial inequality.