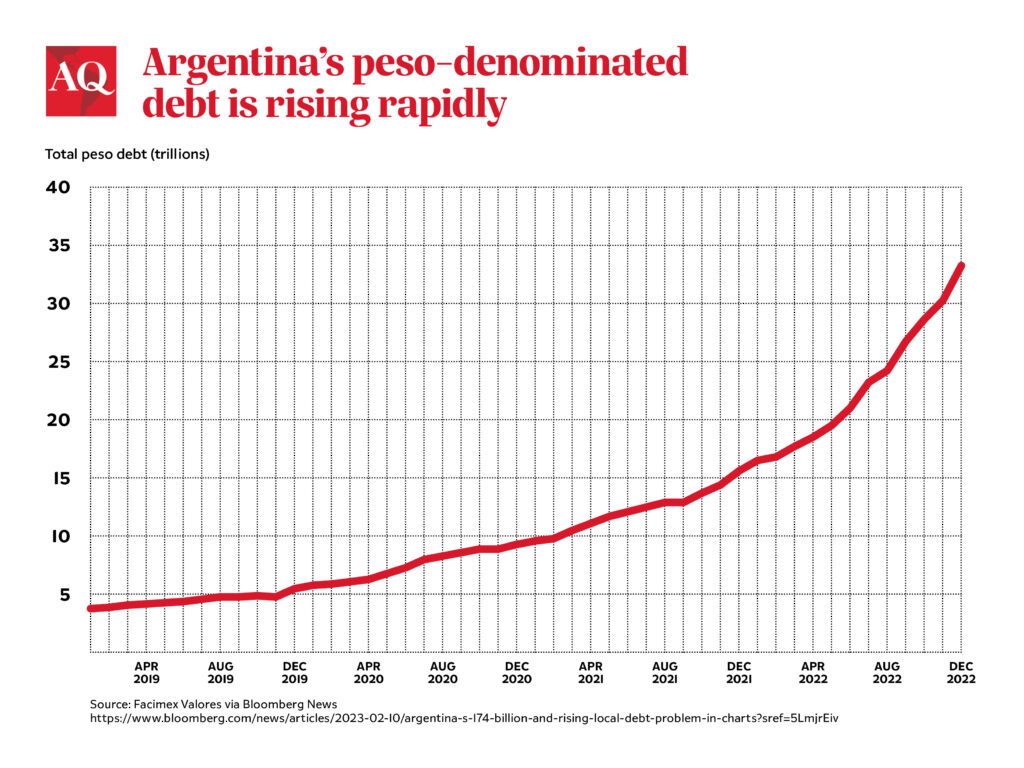

BUENOS AIRES — In the current economic and political debate in Argentina, a commonly heard metaphor is that of a ticking time bomb. As local financial markets dry up despite tight capital controls, the opposition is warning that the government’s search for costly sources of finance may only be contributing to more fiscal fragility down the road.

Recent developments that have put investors on alert include the issuance of “dual” bonds with an implicit exchange rate guarantee, which dollarizes peso debt through the back door before an expected exchange rate correction, or the option to cash government bonds at the central bank at a moderate discount, a liquidity “put” that effectively shortens the bonds’ maturity to zero. Both of these measures were essential to sweeten the recent domestic debt swap.

But investors’ concerns are not only financial. Take, for example, a recent increase in social security benefits for people with insufficient contributions—in a country that already boasts universal social security benefits. This decision, which, according to a Congressional Budget Office estimate, may add about 0.4% of GDP in net expenditures for an indefinite number of years, was at odds with Finance Minister Sergio Massa and his economic team’s commitment to the International Monetary Fund, and reflected the widening cracks within the governing coalition.

It is not clear whether any of this will be enough to meet the financing gap faced by President Alberto Fernández’s government in the last year of his term. Recent challenges have been deepened by the worst drought in over 60 years, which has led to a sharp decline in exports of Argentine cash crops including soybeans and corn. All of this may not offset Fernández’s steady decline in popularity, but it will surely complicate the delicate fiscal rebalancing act of whoever might succeed him in elections scheduled for this October.

Cold wars

This kind of dilemma is not new. Two seminal papers in economics from the late 1980s sought to model the behavior of governments making non-cooperative choices about public debt before elections. In one version, an incumbent likely to lose reelection seeks to increase the fiscal deficit in sub-optimal ways, in order to hardwire its preferences on how money is spent—for example, increasing permanent social security or poverty alleviation programs. In another version, a conservative government is tempted to reduce taxes and increase debt in order to force austerity on a more liberal successor.

In both stories, this deficit bias, which may result in over-indebtedness, financial fragility and even lower investment and growth, is a potential consequence of the natural political turnover coupled with the inability to make credible intertemporal commitments with the opposition, in a context of political polarization and weak institutions.

I have written before on the deleterious consequences of the “continuity trap” in the Argentine context. Here, I want to focus on a “poison pill” variety of the trap.

Imagine, for a moment, that a soon-to-be-unseated incumbent adopts a pattern of expenditure and debt driven primarily by the aim to hinder his opponent and likely successor.

Such a decision is perfectly compatible with other motives. For example, there may be short-term gains in the form of boosts to one’s ego or popularity from overspending on issues favored by the incumbent’s constituency. But those motives are incidental: It suffices that the deleterious consequences of these policy choices be persistent enough to compromise the opponent’s performance and reelection chances, raising the incumbent’s probability of a comeback a few years down the road. Strategic thinking indeed.

What could the opponents do to counter this opportunistic behavior? They could announce, preemptively, that any overspending (say, any item not included in the congressionally approved budget) and related borrowing decisions would be eventually “revised.” This would presumably spook investors, limiting the government’s scope to fund its parting jubilee.

In theory, this game would likely result in a higher deficit and worse debt profile, but kept within certain limits. In the real world, however, it might end in financial and economic disaster.

For starters, the warnings may make funding even more expensive due to the higher probability of a credit event, and riskier, if fears of a restructuring dry out local sources of finance—leading the incumbent to resort to hard-to-service, hard-to-default, dollarized external debt. This would only deepen the opponent’s legacy problems.

Indeed, even if the opponent’s preemptive strategy is “successful” in closing access to new funds, it may cause more inflationary financing—a real danger for a country like Argentina that, as inflation tops 100%, is already walking on a nominal tightrope. Or else, it may fuel a run on the country’s debt and a premature default, which would likely rule out access to voluntary financial markets for a long time—perhaps, for the duration of the next administration. Moreover, if pushed to default, the government may simply reprogram debt to mature the day after the successor takes office, forcing it to debut with yet another restructuring.

True, all the above may make the incumbent look bad in an election year, but for the opponent this would yield a pyrrhic victory, given the short-term nature of political memories.

From continuous crisis to continuous reform

From a long-run standpoint, Argentina has been living, with ever shorter interruptions, in permanent crisis for decades. The country needs more than just fiscal balance to fix its middle-income trap.

The chronic deficit and its associated ills—a weak peso, lack of investment, macro-financial fragility, policy polarization and temporariness—are the result of a gap between social demands and public resources that pierces the social net and derives from, and reinforces, a dense web of privileges. It is the defense of these privileges that ultimately favors the status quo and the non-cooperative behavior among politicians, social leaders and people in general, against reform and real change. A stabilization program will change the country’s history only if it opens the door to permanent reform.

On the stabilization side, we can list a few pending assignments: a primary fiscal balance, an anti-inflationary monetary policy, the recovery of market access, an income policy to ensure a sustainable real income catch up, a smart integration to the world. (This is not a menu: all of the above items are necessary.)

On the reform side, the list is longer. To cite the most pressing: a federal fiscal agreement combined with a tax reform to eliminate or reduce taxes and formalize the economy; a pension reform to sustain the fiscal balance; an enhancement of labor policies with a focus on training and transitions to decent jobs as the key social inclusion tool; a fiscal responsibility law to limit pro-cyclical spending and over-indebtedness. In sum, a program that would need a decade of policy continuity in order to bear fruit.

A non-proliferation treaty

Little can be expected regarding this program in the next nine months. The government has lost credibility and has run out of time. It is not impossible to think of policy coordination beyond the elections and to begin an ambitious agenda to be continued by the next administration. But, given the degree of polarization (between political sides and even within the government), to hope for the agreements that would facilitate this cooperation—the kind on display in Uruguay, or in the Brazilian transition between Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—would seem naive in Argentina today.

Instead, the best that can be hoped for 2023 is for the incumbent government to avoid the poison pill strategy, preventing a cold war with the opposition that, as in most wars, no party can benefit from—least of all an already debilitated economy. In other words, a tacit agreement, without photo-ops or media posturing, that prioritizes the voters—all of them!—over individual interests.

Cooperation does not always yield results at the ballot box these days, but it pays off in outcomes. Confrontation and collapse are never inevitable.