PORT OF SPAIN — The Peterkin family was asleep in their home in the Trinidad and Tobago village of Heights of Guanapo on September 21 when gunmen unloaded weapons—including an assault rifle—on the family of nine. The brazen crime, now known as the Guanapo murders, killed four of the Peterkins’ children, including a ten-year-old girl, and wounded the other five, shocking a nation already indignant about soaring gun violence. Less than a month later, the Trinidad police announced the country’s largest-ever seizure of weapons, including high-powered sub-machine guns, fueling concern about the growing prevalence of assault rifles in the Caribbean nation.

Trinidad and Tobago Prime Minister Keith Rowley mentioned the Guanapo murders in his speech to the United Nations General Assembly, in which he decried the “metastasizing scourge” of gun violence. “This situation has worsened largely because of the accelerated commercial availability (of firearms), coupled with the illegal trafficking from countries of manufacture into the almost defenseless territories of the Caribbean,” he told the United Nations. “This is a crisis shared by almost all the Caribbean territories.”

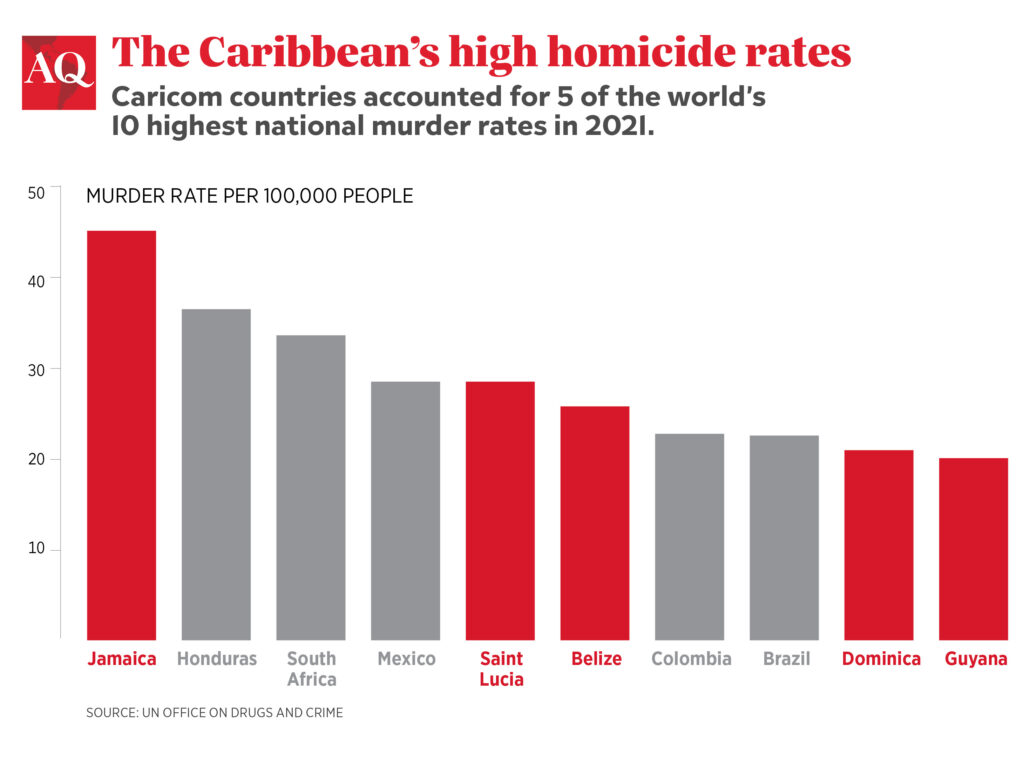

Indeed, Caribbean countries are taking new steps to try to slow the traffic of illegal weapons, many of which come from the United States. The average rate of violent deaths in the Caribbean Community (Caricom) region is nearly triple the global average, according to a report this year by the bloc’s security agency IMPACS, and the Small Arms Survey. Gun violence is particularly acute in Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica—the latter now has one of the highest murder rates in the world. Gang violence has led Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness to declare states of public emergency on several occasions, most recently in June, allowing for warrantless arrests. Some in Trinidad and Tobago are calling for similar measures.

Caricom leaders in April announced a “War on Guns” to combat the illegal weapons trade, which followed years of increasingly vocal complaints across the region. Five Caricom countries this year came out in support of a civil lawsuit filed by Mexico’s government in the United States that seeks to hold U.S. gun manufacturers accountable for the damage caused by weapons smuggled illegally out of America. Lax U.S. gun regulations have become such a point of frustration that The Bahamas Prime Minister Philip Davis this year lamented that “a person’s right to bear arms has unfairly been converted into a [de facto] right to traffic arms.”

Cracking down on trafficked guns

In response to the problem, Caricom’s Implementing Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS) launched the Crime Gun Intelligence Unit (CCGIU) in partnership with U.S. law enforcement agencies to boost cooperation. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced in July that the Department of Justice had named prosecutor Michael Ben’Ary as the first coordinator of Caribbean Firearms Prosecutions. Caribbean officials also insist that responses to violent crime must include reducing demand for guns through mediation programs that can prevent conflicts from spiraling out of control.

But the diffuse network of buyers and the relatively small quantities of arms in each shipment make it a maddeningly tricky problem to address. Trafficking typically involves straw buyers making legal gun and munitions purchases on behalf of smugglers and then concealing them in cargo vessels, postal shipments or on commercial airlines. One shipment of munitions reached Haiti in a container labeled as clothing donations for the country’s Episcopal Church. Gun manufacturers continue to supply retailers that are known to sell to straw purchasers and facilitate suspicious repeated and bulk sales, noted Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, The Bahamas, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in their amicus curiae brief in support of Mexico’s lawsuit.

Trinidad police in August arrested a man for using 3D printing technology to make homemade weapons typically described as “ghost guns,” signaling the possibility of a domestic firearms pipeline. Ghost guns are essentially untraceable weapons. This development is less concerning than the growing import of low-cost “conversion devices” that can turn handguns into automatic weapons, said IMPACS Regional Crime and Security Coordinator Callixtus Joseph. These devices can vastly increase the lethality of weapons for about $15 and typically get through customs easily because officials are only now being trained to recognize them, said Joseph, who described the trend as “frightening.”

Two men have been indicted in the Guanapo murders, but no motive has been determined in the brutal crime that continues to haunt Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidadians are increasingly curbing their night-time outings or avoiding areas where they once traveled freely, as the country remains on track to surpass 2022’s record of 601 murders—the vast majority of which are linked to illegal firearms.

“There’s a reason why most gun crime in the world occurs in the U. S. and surrounding region,” said Jonathan Lowy, president of U.S.-based Global Action on Gun Violence and a lead lawyer in Mexico’s lawsuit against gun manufacturers, in an interview. “And that’s because of the easy availability of guns.”