Just a few years ago, Latin America’s progressive left seemed to be gaining ground. Policies aimed at helping marginalized groups were taking hold in Argentina, where President Alberto Fernández rallied his base in 2020 by passing a law legalizing abortion, and by mandating recognition of a third gender category, “X.” In Chile, Gabriel Boric supported a new constitution described by several media outlets as “woke” and the most progressive in the world.

And it didn’t stop there. Even as Brazil’s ultra-conservative President Jair Bolsonaro actively opposed progressive policies on race, gender and sexuality, these same policies also started to catch on in other countries outside the Southern Cone. In more conservative Colombia, Gustavo Petro allied with feminist and queer social movements during his first attempt at the presidency in 2018. In Peru, Veronika Mendoza’s campaigns in the 2016 and 2021 presidential elections included the use of inclusive language and LGBTQ rights. Abortion rights groups in Mexico and Colombia also obtained historic legal victories after court rulings decriminalized abortion in both countries.

But then came the backlash. Despite initial support, the Chilean electorate voted to reject the new constitution in September 2022, after criticism that it focused too much on identity politics and proposed changes that went beyond what the population wanted. Now the political right dominates a new council elected to help draft a second attempt at a new magna carta.

In Argentina, Javier Milei, a far-right libertarian, was at one point leading the polls for the primaries in August. He has equated progressive politics with “decadence,” and announced he is working on a plan with former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro to stop the international spread of the left.

What explains this setback? One reason is Latin America’s high levels of anti-establishment sentiment, which make it difficult for incumbents to maintain popularity and power. But there’s another dynamic at play, one that’s also present in countries like Peru where the progressive left hasn’t ruled. Across the region, conservative movements and parties are arguing that concepts like anti-racism or the right to be recognized under a chosen gender identity are foreign or irrelevant to Latin American realities, and form part of a broader agenda that seeks to indoctrinate their populations.

This strategy has had effect because in many cases, progressive politics seek cultural change faster than what the population is ready to embrace. To be sure, there have been important and necessary historical advances on sexual and reproductive rights, such as access to abortion and emergency contraception, or gay marriage, won by consistent campaigning from social movements in Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Mexico. Higher awareness of structural racism is also noticeable in varying degrees across the region.

Yet many sectors of Latin American society still have strong conservative identities—or else are too concerned with material worries like poverty and crime to turn their attention to more cultural debates. Even in forward-looking Argentina and Chile, 25% and 31%, respectively, report a low acceptance of homosexuality according to the World Values Survey. This increases to 52% and 68% in Colombia and Peru, respectively. Abortion is far from a settled matter: On average, among 13 Latin American countries, 59% believe it is never justifiable.

Conservatives are aware of this—and are doubling down on rhetoric that appeals to those voters who do not fully share progressive views. “Common sense has triumphed,” Chile’s Kast claimed after the results of the vote for the Constitutional Council. During the campaign, the message was focused on concerns about security and on taking the country back from the perils of the radical left.

In Argentina, popular right-wing writers and influencers like Agustín Laje claim that the progressive left is creating cultural problems where there are none to justify its own existence. Laje is a staunch supporter of Javier Milei, who claims to want to free Argentina from cultural debate to focus on economic stagnation, lack of opportunity and law and order. This has resonated with urban, lower-class sectors of Argentina’s youth frustrated with the apparent failure of their political class.

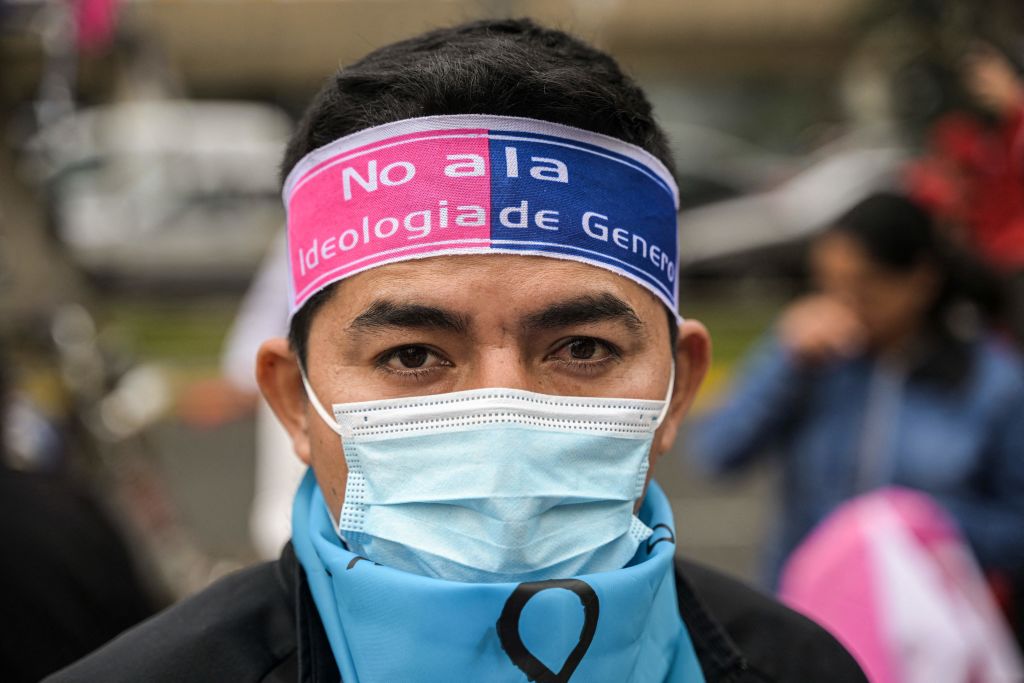

And in Peru, the far right has insisted for some time now that the progressive left is implementing a globalist agenda that seeks to overturn traditional hierarchies and boundaries, pointing to “gender ideology” as an example. To make matters worse, the progressive left’s decision to support left-wing but socially conservative former President Pedro Castillo, now facing charges of conspiracy and rebellion, was such a blunder that the term “caviar,” as in “caviar left”—previously an epithet similar to “champagne socialist”—now refers to a corrupt elite entrenched in the state, much like the “deep state” in the U.S.

Interestingly, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil and Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico have avoided taking firm progressive stances on divisive cultural issues, and have mainly focused on rhetoric aimed at the poorest sectors of their countries, which perhaps helps explains why they enjoy ardent support from their respective bases.

Despite the occasional controversy, Lula mostly did not get embroiled in progressive debates. Instead, he spent time with evangelical groups prior to the runoff, wrote a letter in which he promised to never restrict religious freedom and announced that he’d leave the issue of abortion up to Congress. López Obrador neither welcomed nor decried the Supreme Court’s decision to legalize abortion in 2021, letting the issue play out within civil society.

How should Latin America’s progressives respond to their difficulties? Perhaps by devising a strategy that appeals to a wider net of voters, as conservatives have done, reaching out to groups that may not naturally be part of their constituency. That doesn’t require abandoning their objectives, which have the potential to bring more justice to a deeply unequal region. But failing to do so means running the risk of being branded elitist and out of touch.