RIO DE JANEIRO – Seen through almost any lens, the first year of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s third presidential term was an economic success.

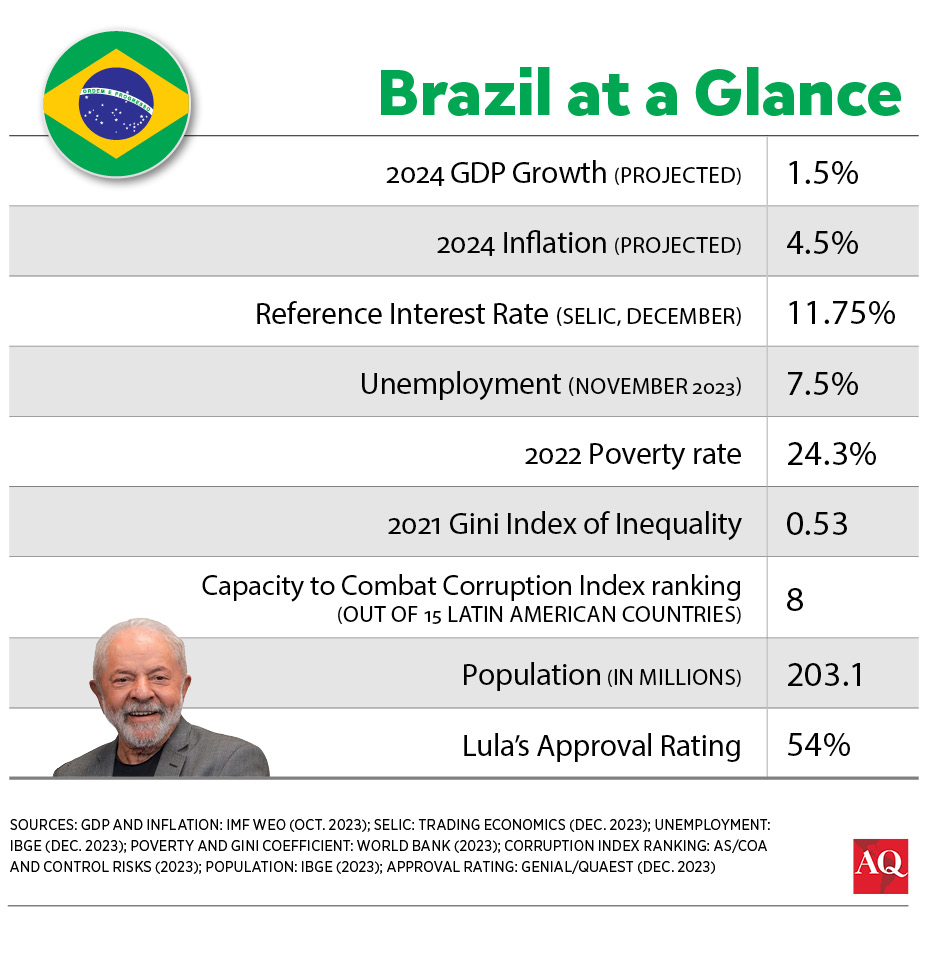

Brazil closed the year with a growth rate around 3%, triple the original forecasts of financial markets. Inflation unexpectedly fell under 5%, unemployment rate fell to its lowest level in a decade, the stock market closed at its highest nominal level ever, and more.

So why is the left wing of Lula’s Workers’ Party still showering his finance minister, Fernando Haddad, with criticism?

“It’s curious,” Haddad mused in an interview with O Globo as 2023 drew to a close, “to see the (memes) that my critics are spreading about the economic situation during this holiday season. They say, ‘Inflation is down, employment is up. Cheers to President Lula!’ My name doesn’t show up – I’m an austericida.”

The Workers Party had used that same word, a combination of “austerity” and “suicidal,” a few days prior in an official statement following its annual convention, to criticize Haddad’s insistence on reducing Brazil’s budget deficit. “You can’t celebrate the results of the stock market, exchange rates, employment rates … and simultaneously release statements claiming everything is wrong and we should change it all and fix it,” Haddad continued.

Shortly after the Globo interview was published, the party’s president Gleisi Hoffman responded to Haddad in the press, saying: “The party has the right – even more, the obligation – to make such warnings. It’s part of our tradition.”

These public clashes, even during a time of relative prosperity, point to challenges that Haddad and Lula are likely to face – this time, with arguably greater stakes – in 2024.

Brazil’s economy remains solid, with growth of 1.5% expected this year. Agencies including S&P Global Ratings have recently upgraded the country’s credit ratings. However, Lula’s government remains under a kind of parole among many investors, who remember how a lack of fiscal discipline derailed his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, and sent Brazil’s economy careening into a deep recession a decade ago. Throughout the past year, markets have wobbled based on Haddad’s fortunes.

With Brazil facing a potential budget crunch as soon as March, Haddad, 60, is once again in the spotlight. Understanding his unique relationship with Lula, his estranged ties with members of his own party, and his own background as the son of a Lebanese shopkeeper will be key to gauging risks and charting Brazil’s course in the months to come.

An early moment of truth

The public struggle between Haddad and Hoffmann is a familiar one to those who have followed Lula’s governments.

Since the opening year of his first term, in 2003, Lula has organized his cabinet and acted as sort of an arbitrator in the disputes between his ministers: Antonio Palocci versus José Dirceu, Antonio Palocci vs. Dilma Rousseff, Rousseff vs. Marina Silva, Rousseff and Guido Mantega vs. Henrique Meirelles… the list is unending. By defending limits to public expenditure and being accused of protecting the interests of the financial sector, Haddad is now in the same place as numerous predecessors.

But which side is Lula taking? Throughout 2023, he faltered a bit. It’s not that he didn’t trust Haddad, whose loyalty has been proven during the Workers’ Party’s (PT, for its initials in Portuguese) good and (especially) bad times. Rather, Lula wasn’t convinced that Haddad’s moderate style was the right one for a country that came out of the 2022 elections divided, and faced an attempted coup during the first week of the new administration.

During the first couple of months, Haddad was the actual minister, but all of his suggestions were either dismissed outright or accepted only after Lula heard from other advisors. For example, in January and February, Lula mordantly criticized Central Bank governor Roberto Campos Neto, a market favorite whom former President Jair Bolsonaro had appointed. Lula also publicly advocated for a revision of the inflation targets, scaring the Brazilian financial sector, which is historically anti-PT.

“Then came a point in which I told him: ‘Mister president, a finance minister can’t win every debate, but he can’t lose all of them either. I need some time to show results. If they’re not good enough, I will leave my position,’” Haddad told me months after the fact.

Having set himself a kind of deadline, Haddad started working on an ambitious agenda that included the approval of a reform that had been stuck in Congress for over 30 years: the overhaul of Brazil’s tax system, which has been described as the world’s most complex and inefficient over the years by the World Bank and others. He also set out to approve the replacement of the Budget Ceiling Law for a new and more flexible fiscal framework, and an unforeseen package destined to cover so-called “rabbit holes” and charge more taxes on millionaire investors and large companies. All of those measures needed a congressional majority, and the government’s base had less than 200 out of 513 representatives in the House of Deputies.

Despite the comings and goings of everyday Brazilian politics, Haddad’s agenda was approved almost in its entirety by the end of 2023.

“Haddad, I want to give you my congratulations. Your serenity, come hell or high water, is what allows us to keep building, alongside members of Congress, entrepreneurs, and the rest of society as a whole, the idea that Brazil is on the right path”, said Lula during a speech in September, right after the tax reform was approved with 365 votes in the House.

A relationship forged in prison

It was the latest chapter in a relationship between Lula and Haddad that could be characterized as like father and son.

Although Haddad was a registered PT member, he had never run for office and had no active party life when Lula chose him to be minister of education in 2005. While in that position, Haddad became notable for implementing affirmative action in federal universities and establishing a widespread scholarship program that opened over 2 million new seats in federal universities, plus another 1.2 million in private universities funded by the government through student loans.

In 2012, while the PT faced one of its many corruption-induced internal crises, then former President Lula chose Haddad as the party’s candidate for the São Paulo mayoral office. Not even Haddad believed it when he was invited – Lula told him he was “the most tucano” of all members of the PT.

“Toucan” was the nickname of the PSDB, the center-right party that was the PT’s main opponent in six straight presidential elections from 1994 to 2014. In the PT symbology, being called a tucano often means being a white, wealthy, moderate, and college-educated male. Adding insult to injury, Haddad is a fan of São Paulo Futebol Clube, the team of the wealthy elite, while Lula is a Corinthians fan, the most working-class club.

Almost 14 years later, Haddad is still seen as the odd man out – a toucan in the PT’s nest.

The son of a Lebanese shop owner who emigrated to Brazil in 1948, Haddad grew up helping his father in the family’s small fabric sales store at the 25 de Março region in São Paulo’s historical center. He got a law degree from the traditional São Francisco School of São Paulo University; then, in 1985, he received a Master’s degree in Economics with a thesis that detailed the shortcomings of the Soviet planned economy – a novelty in the Brazilian left at a time when the USSR still existed. In his doctoral dissertation, Haddad challenged Jürgen Habermas’ interpretation of historical materialism.

“The fact remains that even though I have become known as a public figure in the last few years, I still see myself as a professor first and foremost”, wrote Haddad in the introduction of his latest book, O Terceiro Excluído (“The Forsaken Other”), in which he debates evolutionary biology, social anthropology and linguistics through a Hegelian dialectical lens. The book stems from a series of conversations between Haddad and American philosopher Noam Chomsky, and it will be translated to English by the Dutch publishing house Brill.

With Lula’s support, Haddad won the São Paulo mayoral election in 2012. Four years later, he was hammered by voters when running for reelection, just like most PT candidates that year. In 2018, after Lula was arrested on corruption charges, Haddad experienced the turning point of his career: using his professional prerogatives as a registered lawyer, he was one of the few people who was able to visit Lula in prison without judicial authorization. As time went on, he became Lula’s main spokesman for the outside world – not by chance, the only other politician who visited Lula regularly and battled for the spotlight with Haddad was Gleisi Hoffmann, also a registered lawyer.

With Lula prohibited from running, Haddad ended up being chosen as the PT’s presidential candidate in 2018. His campaign slogan was “Haddad is Lula, and Lula is Haddad.” That was enough to take him to the runoff, but may have been a liability with a broader electorate at a time when anti-Lula and anti-PT sentiment were at a high mark. Bolsonaro ultimately defeated Haddad by a 55-45% margin.

Once Lula was released from prison in 2019, and the annulment of his conviction gave him his political rights back, he entrusted Haddad with the most important mission of the entire campaign: convincing former adversary Geraldo Alckmin to become Lula’s running mate in 2022. For five months, while negotiations were kept secret, Haddad was the only middleman between Lula and Alckmin. Inviting Alckmin, a conservative politician and a former real-life tucano, was Lula’s attempt to nod to a more moderate audience who was afraid of vindictive behavior by the PT once it got back to power.

It was also Haddad who helped lick the wounds and reconnect Lula with his former minister, environmental activist Marina Silva. And last but certainly not least, it was Haddad’s campaign that helped Lula defeat Bolsonaro in the city of São Paulo by a 500,000-vote margin, his first victory in Brazil’s largest city in 20 years.

Overcoming investor doubts

When Haddad’s name was first floated as finance minister, investors’ reaction was disastrous: During the four weeks in which his name was speculated, the Ibovespa index dropped by 7%. There was consensus within the financial sector that Haddad would be a mere longa manus for Lula, someone worried about turning the economy into an electoral machine. Lula did not make things easier by stating in an interview that “the finance ministry has its autonomy, but I was the one who won the election. I know what’s good for the people and what’s good for the market.”

Haddad’s first suggestion as finance minister was to revoke the federal tax exemption conceded by Bolsonaro weeks before the election. Nobody doubted the government needed the money, especially after the country had just approved a budget with a deficit of 230 billion reais, or about $45 billion. However, Lula ultimately denied it, considering it unwise to raise taxes as his first measure back in office. And it was a smiling Gleisi Hoffmann who announced, during a TV interview, that the government would not raise taxes.

The finance minister only recovered fully once Lula gave him time to work and he started to develop a skill nobody in Brasília knew about – political negotiation. Although the government holds a minority in the House of Deputies, Haddad was able to form a surprising alliance with Speaker Arthur Lira, which allowed them to get the tax reform and an also unexpected “tax the wealthy” agenda approved, something the PT had never been able to push forward.

Part of those approvals can be explained by the typical give and take of ordinary pork barrel politics. But that’s not the entire story.

“When Lula won the election, the scenario was chaotic. The previous administration had submitted a fake budget, state governments were on the brink of bankruptcy, and the country remained ignited by Bolsonaro’s false claims of a rigged election,” Haddad told me in December.

“My conversation with Lira and (Senate President Rodrigo) Pacheco was as straightforward as it gets: We are not here to discuss who’s going to win the title. We are discussing whether there will be a championship to be played or not because if we can’t get to terms, this country will collapse. We made a compromise that has taken us this far,” Haddad said.

A tough road ahead

The next few months, however, will put the minister under his most stressful test yet.

According to the fiscal rules set by Haddad himself, Lula’s administration deficit might range from zero to a maximum of 27 billion reais. If by March the pace of tax collection indicates that might not happen, the government will be forced to block between 20 to 23 billion reais in spending. Markets are not optimistic.

Complicating matters: The 2024 budget that Haddad approved in Congress projects the collection of around 50 billion reais from private debt negotiations and another 50 billion reais from rulings at the Federal Revenue Court of Appeal. There is little certainty that all this money will actually go to public coffers.

Furthermore, revenue collection is historically smaller in Brazil during the first quarter. So in Brasilia there is huge uncertainty about whether Lula might take the chance to alter the fiscal deficit target to between 75 and 100 billion reais, a range more in line with private estimates. Lula’s powerful chief of staff Rui Costa and the omnipresent Gleisi Hoffmann both advocate for a larger fiscal space, with the argument that the government needs an electoral victory in 2024 municipal elections to avoid losing ground to the pro-Bolsonaro opposition.

Lula himself shared a similar thought in October, at a breakfast with journalists: “We will barely get to the zero-deficit target, even because I don’t want to cut investments in construction works. If Brazil ends up with a 0.5% deficit, what does that actually mean? A 0.25% deficit, what is it? Nothing. Basically nothing. I will not establish a fiscal target that forces me to start the year cutting billions from construction works that are vital for our country. Many times, the market gets too greedy and starts to demand a fiscal target that they know is unfeasible.”

In reaction to his words, the main stock index dropped, Brazil’s currency lost value and the market started panicking. Under pressure, Haddad carved out a moral victory: He was able to convince Lula to not speak on the fiscal target again, and let Haddad state publicly that the zero-deficit target would remain in place. Haddad then spoke to some of the main bankers in the country and asked for help to convince Congress to approve his taxation agenda. Improved forecasts for the U.S. economy also helped put Brazilian markets in a better mood – at least for a while.

The debate over the fiscal target is set to return in March, and it’s not clear whether Haddad will have as much gas left in the tank.

The political chaos and divisions that helped focus minds in early 2023 has somewhat dissipated, so the moderate faction of the opposition might not have the same goodwill in helping Lula’s government anymore. Meanwhile, it’s clear the PT will intensify their hostility towards Haddad if there are cuts on social and welfare programs – even if they are authorized by Lula himself.

The campaign for mayoral elections will probably worsen polarization even further, and part of Lula’s cabinet has been treating these elections as a preview of the 2026 presidential race. PT victories might discourage potential 2026 adversaries such as São Paulo governor and Bolsonaro ally Tarcísio de Freitas. A sound defeat, on the other hand, might make Lula rethink his reelection chances and refocus attention on who might inherit the PT’s leadership – a race that may include Haddad, and could complicate his job even more.

Confronted by this troubling scenario, Haddad answered me with a good-natured shrug. “Nobody said it was easy” being finance minister, he said. “Problems are part of the office’s job description.”

($1 = 4.93 Brazilian reais)

—

Traumann is a journalist and a Brazilian political risk analyst. He was a spokesperson for the Brazilian presidency during Dilma Rousseff’s first term. Traumann is the author of O Pior Emprego do Mundo (“The Worst Job in the World”), which described the achievements and mishaps of 14 Brazilian finance ministers. More recentlyl he co-authored, with political scientist Felipe Nunes, the book Biografia do Abismo (“Biography of the Abyss”), about Brazilian political polarization.