Businesses and entrepreneurs in Venezuela are responding to the country’s crippling economic crisis in all sorts of ways. Many are simply closing their doors – not surprising in a country whose GDP shrank by at least 10 percent last year.

But others have reinvented themselves to survive in the country’s off-kilter economy, as new ways of making a living have arisen in response to the (previously non-existent) needs of a population under duress.

Here are five ways that Venezuelan businesses and businesspeople have responded to the scarcity, loss of purchasing power and brain drain that crisis has wrought.

Craft… everything

The corn flour used to make arepas, the emblematic corn-cake eaten by Venezuelans of all economic stripes, has been hard to come by for some time. Empresas Polar, the maker of the once ubiquitous Harina PAN, says the government is strangling them with regulations that make it impossible to keep store shelves stocked with this dietary staple.

But to make corn flour yourself, all you need is time, corn grains and a hand-cranked or electric mill. Many Venezuelans have begun to do just that, either for their cooking needs at home or to sell prepared corn-dough on street corners.

There are few – if any – restrictions on who can sell it. It can be as simple as setting up a plastic table and a cardboard sign. One street vendor near a municipal market in Puerto Ordaz, a city in the western state of Bolívar, sells corn-dough, home-made butter, and queso blanco using just a table and umbrella as his storefront. “It’s what people are buying because they can no longer find products like Harina PAN,” he told AQ.

The trend doesn’t stop with food – homemade cleaning products are also becoming more common. In 2014 Clorox closed its branch in Caracas, alleging that government restrictions, interruptions in the supply chain, and economic uncertainty made it impossible to operate. The Venezuelan government seized the installations vowing to increase production, though that promise has yet to come to fruition.

In the meantime, some Venezuelans are making a living by selling bleach and liquid soaps they mix themselves and store in recycled plastic bottles. Some sell to customers who bring their own containers – a way for everyone involved to save a little more money.

Basic imports

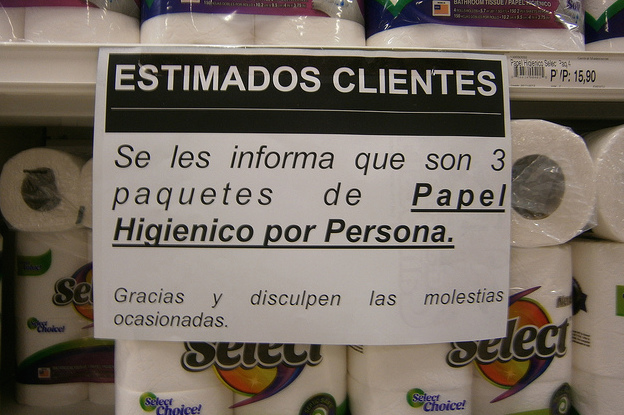

President Nicolás Maduro’s government has imposed strict price controls on basic food items in an attempt to make them more accessible. As a result, producers often have to sell at a loss, causing many to simply stop producing. That’s one of the reasons why the shelves of most major supermarkets and pharmacies are emptier every day.

In response, gourmet grocery stores have been showing up increasingly over the past year. They require less volume because their prices aren’t regulated, so they fill up their stores with imported olive oils, cereals, cheeses, ham and other products only affordable to the middle and upper classes.

Others have come up with unique ways of getting around price controls. A national chain of clothing stores called Traki, for example, has begun selling imported food and other hard-to-find products alongside its t-shirts and pants. The store isn’t subject to price controls, and its products aren’t subsidized or sold at a loss. A 1.5 lb bag of Tide washing powder at Traki can cost almost a quarter of the current monthly minimum wage.

Counting cash

For years, the Central Bank of Venezuela refused to emit high denomination bank notes, and thanks to the estimated inflation rate of 700 percent (and rising), it takes a wad of bills to cover even the smallest expenses like paying for a taxi or buying a cup of coffee. The government began to slowly introduce higher-denomination bills in December, but so far they account for just 1 percent of circulation.

In response, many small businesses have found a niche selling money counting machines to those desperate to keep track of their mounting piles of bills. The demand has gotten so high that the machines have replaced iPads and smartphones on the shelves of many electronics stores.

“At the end of the day we are Venezuelans trying to outlive the crisis too,” Elías, the owner of an electronic store in Puerto Ordaz, told AQ. His shop has placed the machines where they used to feature TVs.

Personal “cash advances” have also become a fruitful business. ATM lines can take hours and machines limit how many bills customers can take out at a time – usually barely enough to buy lunch. Some vendors sell cash at up to 150 percent of its value and accept payment via debit card. The practice is illegal but widespread, especially in small towns where there are few if any ATMs.

Night life

Despite increasing costs and crime rates, nightlife is still alive in Venezuela. Clubs and bars offer discounts on certain days to attract clients, and on paydays they often fill up to capacity.

“You go on a night out and feel as if nothing was happening,” Francis, a lawyer, told AQ. “I guess people just want to forget the crisis for a moment.”

But the most successful venues are those that have taken affordability out of the equation. By focusing on a higher-income clientele that can still afford to spend their money on drinks and a good time, bars and clubs are finding ways to stay afloat. At Lagar’s, a recently opened bar in Puerto Ordaz, a tab can easily run to more than twice the monthly minimum wage. “I can make over 100,000 Bolívars on a good night,” one of the waiters told AQ. “It’s a place for wealthy people.”

Language learning

Venezuelans have plenty of reasons to emigrate, and many are registering for language classes, especially English, to prepare. Unlike the other businesses on this list, language institutes haven’t changed their model – the product they offer has just become more of an urgent need for many Venezuelans.

But the overall numbers of people enrolled in language schools haven’t changed as much as you might think. That’s because diminished purchasing power has left many one-time students unable to pay, with those new students who can still pay simply taking their place.

“The numbers are stuck. We could see a steady growth if we invest more on advertisement,” Teo Castillo, director of language school Censol Guayana, told AQ. Castillo said the school wasn’t making enough money to promote its courses.

The ebb and flow in language school enrollment is a particularly dire illustration of Venezuela’s current reality. Purchasing power is decreasing to the point that many can’t afford anything but the most basic goods and services (if that). Those who do still have disposable income choose to invest in things that will increase their chances of leaving the country.

Businesses, like people, are transforming themselves in increasingly radical ways as Venezuela’s crisis deepens – a tragic story of perseverance.

—

Hernández is an economist and freelance writer from Venezuela