This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the battle over fake news | Leer en español | Ler em português

On October 28, 2018, just a few hours after Jair Bolsonaro was voted the next president of Brazil, Cristina Tardáguila received an urgent call from her lawyer. He had reserved a seat in her name on a flight to Spain, departing just a few days later. “It isn’t safe for you in Brazil anymore,” she recalled him saying.

Tardáguila is the founder of Agência Lupa, Brazil’s first and most prominent fact-checking agency. Based in Rio de Janeiro since 2015, the agency at first received near-unanimous accolades for trying to help Brazilians sort through a growing mass of dubious content on platforms like WhatsApp, YouTube and Facebook. But by 2018, the year that saw a historically bitter presidential election between conservative Bolsonaro and leftist Fernando Haddad, the tone had changed.

The volume of fake news quadrupled that year. Tardáguila and her colleagues at Lupa were receiving as many as 56,000 threats per month. They came from across the ideological spectrum, but the majority were from Bolsonaro supporters. Around 20% of them appeared to be generated by bots.

“Filthy scum,” one direct message on Twitter read. “When the time comes we will come looking for you, one by one.” A viral cartoon caricatured her and two other prominent women fact-checkers half-naked and leashed like dogs. George Soros was depicted holding the leash and dangling a wad of dollars above them.

Other fact-checkers were also targeted. Truco, another agency, closed down amid a barrage of serious threats. Some warned of an attack with acid chemicals.

At first, Tardáguila ignored her lawyer’s advice. She didn’t want to uproot her family or abandon her colleagues, many of whom had also been threatened. She hoped that after the elections things would calm down. But the threats never stopped. She thought about making a formal complaint to the police in Rio de Janeiro. But a source inside Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court (TSE, for its initials in Portuguese), the highest authority overseeing elections, warned her not to. Rio’s police were just as polarized as the people targeting her on Facebook and Twitter, her source said. In the best-case scenario they would ignore her complaint. But they could also harm her by leaking her personal information, such as her home address, to those who wanted to cause her harm. In May 2019, tired and scared, she finally left Brazil.

Tardáguila’s story is just one face of the increasingly divisive and dangerous war over fake news and misinformation in Brazil. The battle over what is true or false, who gets to decide, and whether and how to punish offenders, is tearing at the very fabric of the country’s young democracy. Fake news is badly eroding the public’s faith in Brazil’s voting system ahead of presidential elections in 2022. It is also at the heart of a constitutional crisis pitting Bolsonaro against Brazil’s Supreme Court, which the president and his followers have threatened to disobey or even try to close down to protect their so-called freedom of speech. The question of how to deal with the tide of misinformation, while also not curtailing essential liberties, poses an extraordinarily difficult dilemma for policymakers, technology companies, the justice system and others, with no easy solutions in sight.

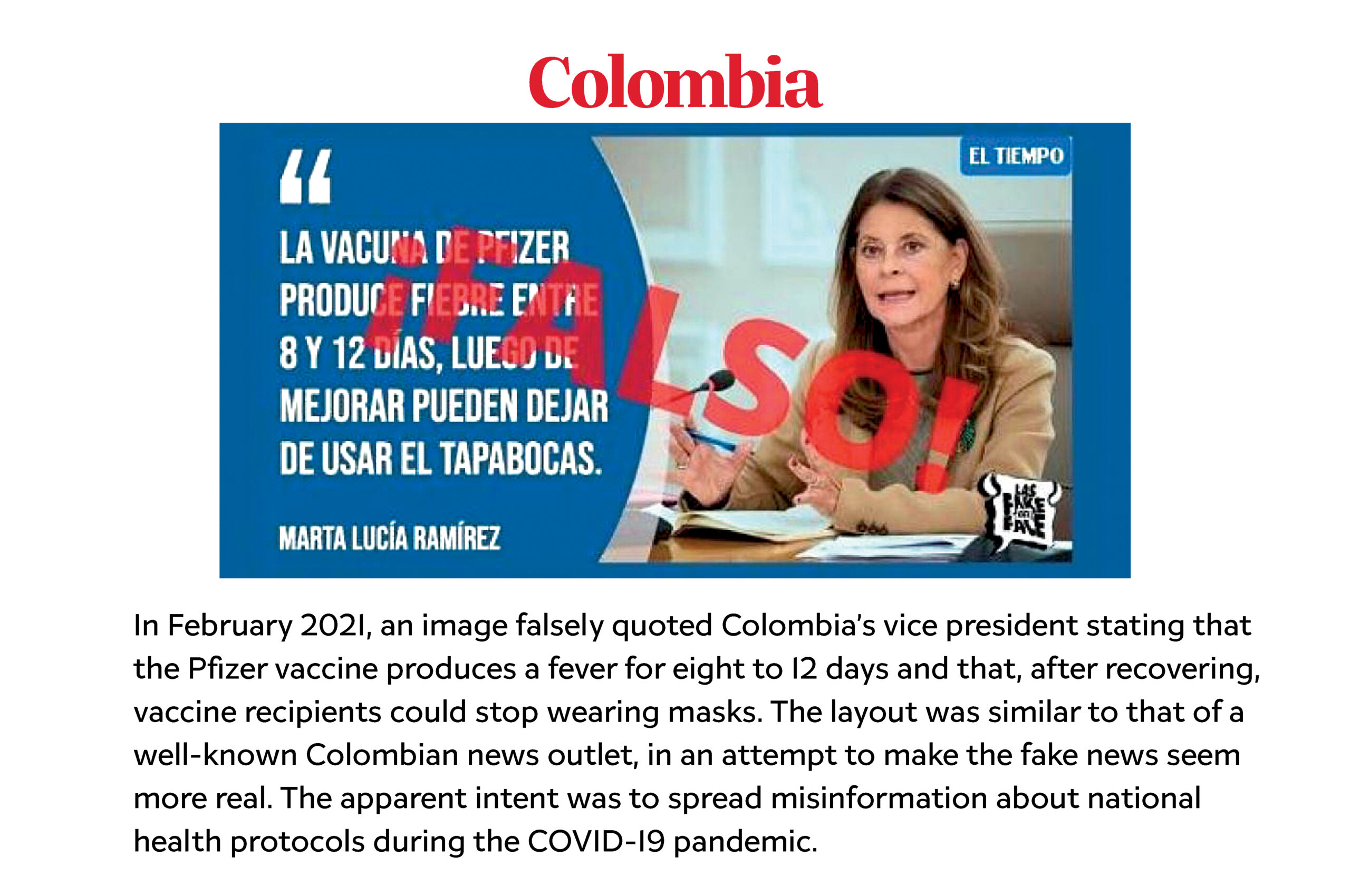

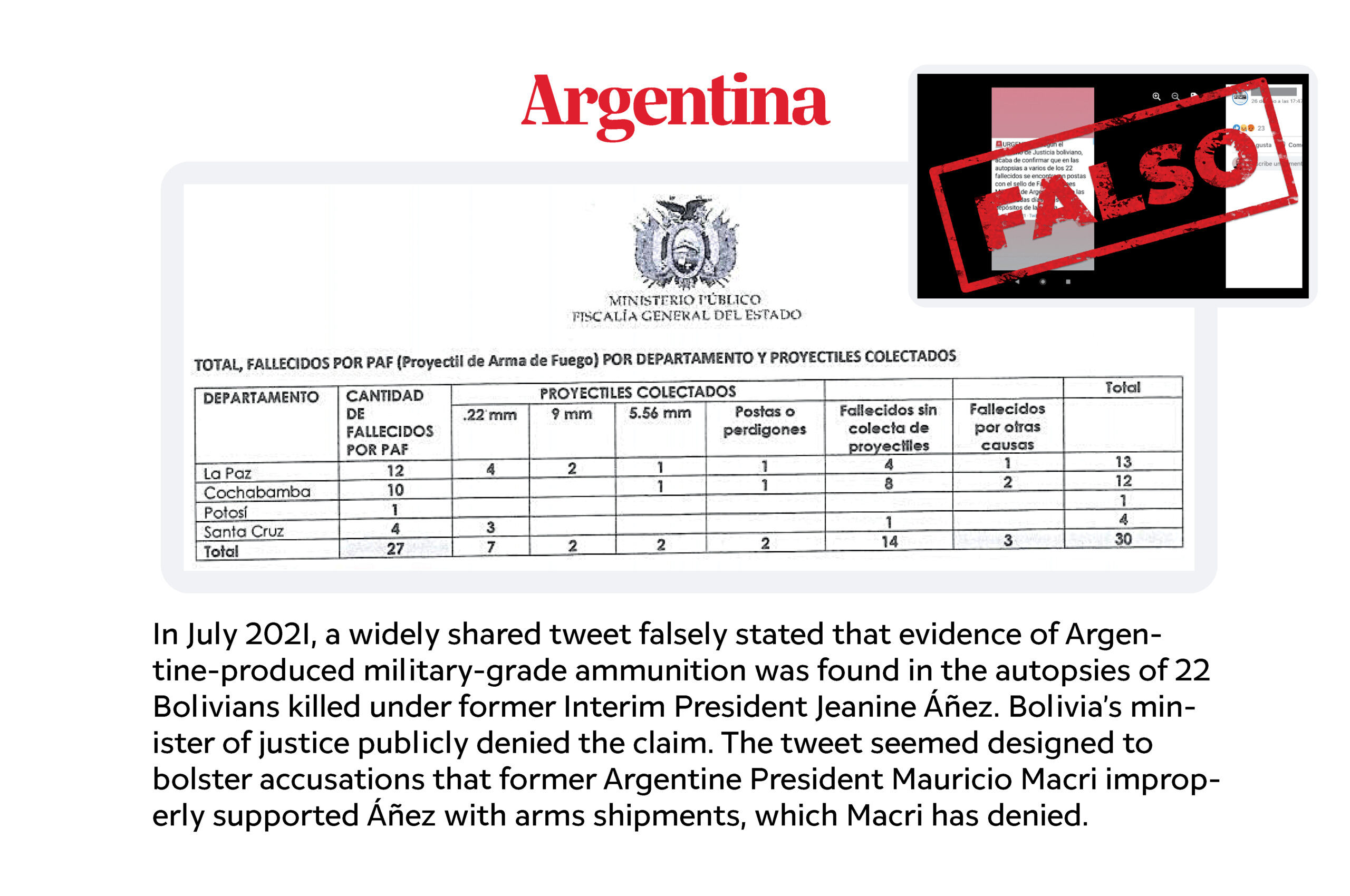

Brazil is certainly not the world’s only country with a misinformation problem. Latin America has some of the world’s highest usage rates of social media, and among its lowest levels of trust in government and other institutions, making many countries especially fertile ground for fake news. In Colombia earlier this year, false reports about policemen raping girls were posted on Twitter, in an apparent attempt to motivate anti-police sentiment among the millions of anti-government protesters who took to the streets. In Peru, a dubious poll that showed Pedro Castillo 30 points ahead of Keiko Fujimori was widely shared on numerous platforms. The massive spread of fake news related to the pandemic, such as supposed miracle cures like hydroxychloroquine, may be one reason why Latin America has accounted for about a quarter of the world’s confirmed COVID-19 deaths despite having just 8% of its population (along with other factors, such as inequality and underfunded public health systems).

But even by regional standards, Brazil appears to be a special case. As a Colombian reporter, I thought we had a bad problem with misinformation in my country; but I was consistently surprised while reporting this story by the amount of fake news spread even by government officials, and by Brazilians’ heated debate around what is true or false. It’s clear that, if the United States was a main battleground in the global debate over misinformation during its 2020 presidential election, Brazil could be the epicenter for a similar battle as Bolsonaro seeks reelection next year. Indeed, figures from around the world, from the U.S. conservative icon Steve Bannon to executives at Silicon Valley technology companies, are all taking an interest in the debate over misinformation in Brazil. What happens here over the next 12 months, and whether Brazilians are somehow able to defuse what looks like a ticking time bomb, will have implications everywhere.

The online war

Fake news tends to thrive most in polarized societies, said Michael Beng Petersen, a professor at Denmark’s Aarhus University and a renowned expert on misinformation. It is no surprise then that Brazil has such a serious problem.

Many analysts trace the beginning of Brazil’s current period of polarization to the 2003–2016 rule of the leftist Workers’ Party (PT). The era was defined at first by generalized prosperity and a large expansion of the middle class, but it ended in scandal, rising crime and the worst recession in Brazil’s history. The 2016 impeachment of the PT’s Dilma Rousseff divided the country. Meanwhile, the Lava Jato anti-corruption investigation starting in the mid-2010s stained all political parties and generated a widespread backlash against Brazil’s entire establishment, said Sergio Lutdke, of Projeto Comprova, a Google-sponsored conglomerate of journalists focused on investigating disinformation.

Brazilians at first expressed their frustration in a series of popular protests that drew 1 million people to the streets in 2013. But the main battlefield quickly shifted online, said Ludtke. Brazilians had already been among the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of social media, embracing Orkut, a social media platform owned by Google, years before Facebook or Twitter conquered the world. Although Orkut shut in 2014, Brazil today has around 160 million social media users, more than any other country outside of Asia except the United States. Brazilians also spend more time on social media than any other country except the Philippines, according to a digital report by We Are Social, a marketing agency, and Hootsuite, a social media management platform.

Into all this ferment came Bolsonaro. A peripheral figure in Brazilian politics prior to the 2018 election, it’s impossible to imagine Bolsonaro’s rise without the aid of social media. His aggressive attacks on the PT, women, LGBT people and others earned him widespread condemnation among Brazil’s traditional media and politicians—and an increasingly loyal following online. “It’s like (Bolsonaro) knows what words to say to play the algorithm” and bolster the size of his audience, said Thomas Traumann, a political analyst. Even today, Bolsonaro’s followers tend to see social media as the core pillar of his power and popularity. They believe that without it, public debate would be monopolized by traditional newspapers and broadcasters such as O Globo that have consistently questioned or opposed Bolsonaro’s rhetoric. This helps explain why any attempt to regulate social media prompts such immediate and ferocious opposition among many bolsonaristas.

The problem is that the bolsonarista online space has been consistently plagued by fake news and misinformation—to an extent that it doesn’t seem accidental, experts say. During the 2018 campaign, memes circulated falsely stating that Haddad, the PT candidate who faced Bolsonaro in the runoff, had, while mayor of São Paulo, distributed thousands of baby bottles with penis-shaped teats throughout the city’s childcare facilities as part of a “gay kit” that sought to make homosexuality more acceptable among children. Other fake news during the campaign claimed Haddad wanted to legalize pedophilia, and allow the state to decide which gender children should be assigned once they turn five years old.

Some evidence suggests the pro-Bolsonaro fake news machine is a professional operation run by the president’s allies and followers. A Federal Police investigation into the organization of anti-democratic protests held in 2020 pointed to the existence of a so-called cabinet of hate—a group of young aides, allegedly led by Bolsonaro’s politically active sons, dedicated to spreading fake news and attacks on journalists and government opponents. (Bolsonaro’s sons and others strongly deny the “cabinet” exists or that they spread fake news.) During the 2018 elections, an investigation by Folha de São Paulo revealed an industry of PR agencies that sold WhatsApp packages that allowed for fast dissemination of messages. Companies aligned with Bolsonaro allegedly paid up to $2.3 million for the service, Folha said. The investigation claims the PR agencies had illegal access to WhatsApp user databases sold by several digital companies.

Since becoming president, Bolsonaro has continued to rely on social media, to an even greater extent than most contemporary leaders. On his Facebook channel he broadcasts live speeches to 10.7 million followers every week. He often talks for more than an hour, complaining about business as usual in Brasilia and sometimes making fun of guests. (In one live show, he called a Black supporter a “roach breeder” in reference to his hair.) He and his followers have also used Twitter and other platforms to make false attacks on journalists, including those who work at fact-checking agencies. Eduardo Bolsonaro, the president’s son, falsely claimed Patrícia Campos Mello, the reporter who led the Folha investigation into the allegedly illegal use of WhatsApp groups, offered her sources sexual favours to get damning information about the president. (Campos Mello won a lawsuit against Bolsonaro for moral damages, and a judge ordered him to pay a $5,500 fine.) “Undermining the press is part of (Bolsonaro’s) disinformation campaign,” said Pablo Ortellado, a philosopher and coordinator of the University of São Paulo’s investigation group on public policy and access to information. By calling journalists liars he “disarms something that could prove him wrong.”

To be clear, fake news has also been a problem on the Brazilian left — several PT officials recently promoted or shared a video that falsely suggests an assassination attempt against Bolsonaro in 2018 may have been staged and then covered up. But pro-democracy advocates have been disturbed by what they see as evidence of a professional misinformation operation in the service of the government. A September report by Reporters Without Borders counted nearly half a million tweets attacking the press over a three-month period in Brazil, with at least 20% of them likely coming from automated or “bot” accounts. Research by Raquel Recuero, director vice president at the Federal University of Pelotas’ Laboratory for Media, Discourse and Social Networks Analysis, suggests there is disproportionate, immediate and obviously coordinated response on social media almost every time the president is attacked or says something controversial. It happened, for example, when Veja, Brazil’s leading weekly publication, published a story in 2018 about Bolsonaro’s divorce of his second wife. Minutes later, social media was flooded with false claims that Veja received money from the PT to lie about Bolsonaro. “If it was organic there would be several stories, with different explanations,” coming out at different moments in time, said Recuero.

Enemies everywhere

The relentless flow of misinformation has provoked a counter-reaction from the courts, Internet regulators, technology companies and Bolsonaro’s political opponents. Some efforts at getting the problem under control seem promising. But others seem tinged with politics, while some contemplate cures that may be as bad or worse than the disease itself.

On the judicial side, there are at least four major legal investigations or inquiries involving fake news, some with overlapping remits. The first, and perhaps most controversial, is a Supreme Court inquiry into the spread of disinformation by Bolsonaro’s followers, as well as threats they have made against members of the court. The investigation is being led by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, a former public prosecutor and minister of justice. The president himself became an investigated party in that inquiry in August, after claiming that the 2014 and 2018 elections, the latter of which he won, were plagued by fraud (Bolsonaro claims he should have won on the first round, but admitted he had no proof). A criminal conviction against a sitting president is highly unlikely.

The investigation has contributed to the escalating crisis between the Court and Bolsonaro, whose supporters contend the probe is unconstitutional, arguing the Supreme Court cannot be the victim, investigator and judge at the same time. Nevertheless, the case has deeply shaken Bolsonaro’s inner circle, as Federal Police have searched the homes and offices of dozens of allied businessspeople, bloggers and politicians. De Moraes has also authorized arrests, including that of Roberto Jefferson, a staunch Bolsonaro ally and the head of the right-wing Brazilian Labour Party. According to the justice, Jefferson was part of a ring of criminals who sought to “destabilize republican institutions” by spreading fake news. Following Jefferson’s arrest, Bolsonaro asked the Senate to impeach de Moraes. Traumann, the political analyst, said Jefferson’s case especially bothers the president because he fears the court could one day also go after his sons for their alleged role in spreading misinformation.

The other probes include a Congressional investigation of criminal misinformation networks, which has asked the Federal Police to determine whether Senate computers were used to spread fake news on Instagram. That investigation has also asked social media companies to give them the names behind several social media profiles, including accounts that were accessed from the congressional office of Eduardo Bolsonaro. A separate probe by the TSE, the electoral body, has looked into allegations that Bolsonaro and supporters have spread misinformation regarding next year’s election, including unproven claims that Brazil’s electronic voting machines are susceptible to fraud. The fourth investigation, created by the Senate, is exploring misinformation and other aspects of the Bolsonaro government’s ineffective response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Posts on social media have claimed the pandemic is exaggerated by left-wingers, that hospitals are actually empty, and that people are being buried alive to drive up death rates. The president himself has insisted, despite medical evidence to the contrary, that “early treatment” drugs such as hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin and azithromycin are effective against COVID-19. By October 2021, more than 600,000 people had died of COVID-19 in Brazil, a toll surpassed only by the United States.

Taken together, these investigations have heightened the possibility that Bolsonaro could be impeached by Congress or declared ineligible for the 2022 election. In response, the president has increasingly warned that a “rupture” in Brazil’s democracy may be imminent. He has also stepped up his attacks on Brazilian institutions, with a focus on the court and specifically de Moraes and Luis Roberto Barroso, a court justice who is also head of the TSE, the electoral body. The president gathered hundreds of thousands of his supporters to stage a protest against the Supreme Court on September 7, Brazil’s independence day, and declared that he would never again comply with an order from de Moraes, which would be illegal. The declaration prompted a forceful response from members of other branches of government, including Barroso, who refuted Bolsonaro’s claims of electoral fraud point by point, calling them “empty rhetoric.”

A few days later, Bolsonaro appeared to back down, saying in a letter that his threats toward the Court came “in the heat of the moment” and promising to respect other branches of government. But few observers expected the truce to last.

No easy solutions

In Congress, legislators have also tried to fight back, introducing at least 45 bills aimed at curbing the spread of fake news. But many of the measures carry significant risks. Several would modify the Civil Rights Framework for the Internet, changing its rules on safe harbor, which currently give Internet providers and platforms immunity in case third party content violates any laws. This would expose the companies to major legal risk, and transform their business models. Other proposals seek to force social networks to remove objectionable content no more than 24 hours after a user files a complaint (currently they remove content that violates their terms of agreement, or when complying with a court order). Some bills would allow users who share fake news to be prosecuted as criminals, even if they are unaware that they are spreading lies. There is even a proposal to limit to 1,000 the number of users who can receive a WhatsApp message. Meanwhile, some members of Congress and the judiciary are pressuring tech platforms to ban Bolsonaro and his allies, in the same way many did with Donald Trump in early 2021.

Aware of the threat, Bolsonaro is taking countermeasures of his own. On September 6 he signed an executive order that attempted to ban platforms from de-platforming users (as happened to Trump) or taking down most content without a court order. The New York Times called the decree “the first time a national government has stopped Internet companies from taking down content that violates their rules.” The decree was ruled unconstitutional a few days later and thrown out by Congress, but most experts believe Bolsonaro will continue to try to use all tools at his disposal to protect his allies.

In the meantime, social media companies feel caught between Bolsonaro and his opponents, facing the dual threats of onerous regulation or a free-for-all environment that would further diminish public trust in their platforms. “Our mission is to organize information and make it useful to the world,” said Marcelo Lacerda, director of Google’s Government and Public Policy team in Brazil. “If we have bad content, we risk jeopardizing our relationship with the users, content creators and advertisers that support our business.” On some platforms, it’s not even clear regulation is possible. WhatsApp is the most popular social media platform in Brazil, and therefore where most fake news propagates, but messages there are encrypted. This plays in Bolsonaro’s favor, says Traumann. “In America they restrain Donald Trump by taking him out of Twitter and Facebook,” but if they do that with Bolsonaro, they won’t change anything because he can still reach Brazilians through WhatsApp. Many bolsonaristas have begun migrating to Telegram, which they view as even less likely to be regulated.

Proposals for regulation would complicate the way networks operate, not only in Brazil, but around the world, argued Marcel Leonardi, an Internet lawyer who represents many social media companies in Brazil. WhatsApp doesn’t currently have an operating system that can limit a message’s reach to 1,000 users, said Leonardi. It would have to create one, and apply it throughout the world, just because Brazil demands it. Instead, Leonardi said, companies should be allowed to continue to develop tools to fight disinformation. Facebook and YouTube use a combination of machines and humans to flag content with fake news. In Brazil, YouTube has taken down videos where Bolsonaro claims ivermectin cures COVID-19. Facebook removed dozens of accounts that spread fake news, some of them linked to associates of Bolsonaro and his sons. Even WhatsApp has conducted investigations that have led to the suspension of hundreds of accounts. Social media companies are also working with the TSE to understand how to best fight fake news about next year’s election. On August 16, Youtube complied with a TSE order to suspend payments to 14 channels that warned of voter machine fraud.

Google believes it can help fight disinformation through other means. In Brazil, for example, it has invested $2 million in Educamidia, a program that helps teachers teach media literacy, and created Comprova, an initiative that employs journalists to disprove fake news. Yet social media companies know they can only do so much. “We understand the fight against misinformation as something we cannot do on our own,” said Lacerda, the Google director. He believes policymakers should involve educators, tech companies, lawyers and civil society to come up with joint solutions for fake news.

Democracy at risk

It’s unclear whether any of this can prevent what looks like a looming crisis in 2022. With Bolsonaro’s approval rating at all-time lows, polls suggest he would lose next October to several major candidates, including his most bitter rival, leftist former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the PT. With his back against the wall, Bolsonaro seems likely to use all tools at his disposal, including fake news, and could try to incite violence or otherwise undermine democracy, said Claudio Couto, a political analyst. “For him, it’s all about staying in power.” Bolsonaro has repeated on several occasions that he sees only three potential outcomes for himself: “prison, being killed, or victory.”

No one knows whether the Brazilian military, or other government institutions, would support Bolsonaro on an authoritarian adventure. Indeed, the only thing that seems certain is that misinformation will continue to corrode Brazilians’ faith in their institutions and in democracy itself. In a speech in mid-September, following his latest confrontation with the Supreme Court, Bolsonaro downplayed the threat, and seemed to nod to his tactical plans for the year ahead. “Who never told a little lie to their girlfriend? If you didn’t, the night wouldn’t end well,” he said to laughs from an audience of supporters. “Fake news is part of our lives.”