This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s election super-cycle | Lea este artículo en español aquí |

In Latin America’s 2024 electoral super-cycle, voters seem likely to reward leaders who address their most fundamental needs—in some cases regardless of whether they value democracy, clean government or the rule of law.

That is a notable shift, following several years in which a “throw the bums out” anti-incumbent sentiment was the prevailing trend in the region. As readers of AQ know well, 20 of the last 22 free and fair presidential elections in Latin America dating back to 2018 have been won by the opposition, as voters lashed out against stagnant living standards, corruption and a surge in organized crime. But that trend could change this year, thanks to leaders who have enjoyed some measure of success—even if it has come at a cost.

Indeed, in El Salvador, Nayib Bukele is poised for reelection due to his security policies—which have contributed to a reduction in crime, but also imprisoned thousands of Salvadorans without due process. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s preferred candidate Claudia Sheinbaum leads the polls in Mexico, leveraging the incumbent’s popularity from social programs, despite his repeated attempts to undermine independent institutions. In Panama, former President Ricardo Martinelli, convicted for money laundering, is a leading candidate after having governed previously during a time of economic prosperity.

Some of this year’s elections will be more traditional. In the Dominican Republic, President Luis Abinader, whose popularity is based on an anti-corruption platform, is leading the polls. Uruguay remains a case study of how democratic institutions over time can deliver on people’s concerns, though organized crime poses risks.

Venezuela merits separate treatment. While Nicolás Maduro’s regime has committed to holding an election, almost no one believes it will be genuinely free and fair. Indeed, a true return to democracy demands more than having a vote.

The following is a brief overview of Latin America’s elections—and one “election”—in 2024:

Meet the candidates in El Salvador’s 2024 election

EL SALVADOR: Rights vs Security

Since entering office in 2019, Bukele has taken several steps to erode democratic safeguards. In 2021, he used his majority in the National Assembly to politically take over the Supreme Court’s Constitutional Chamber and the Attorney General’s Office, adopt norms that enabled the dismissal of hundreds of lower-court judges, extend his control over the judiciary, and adopt legislation and a state of emergency that lowered crime rates at the expense of rights. The packed Constitutional Chamber paved the way for his reelection campaign, despite constitutional prohibitions.

Yet Bukele’s popularity stems from policies that successfully reduced violence rates in a country previously plagued by horrendous gang crimes, through a strategy supported by a communications campaign.

In February’s elections, the question is not whether Bukele will win (he will), but by what margin. A decisive win could further weaken political opposition, independent journalism and civil society in a context of shrinking civic space. The elections follow a gerrymandering effort by Bukele, enhancing his party’s chances for a legislative majority. This would later enable him to influence key appointments, including Supreme Court justices, Supreme Electoral Tribunal members and the attorney general.

Meet the candidates in Panama’s 2024 election

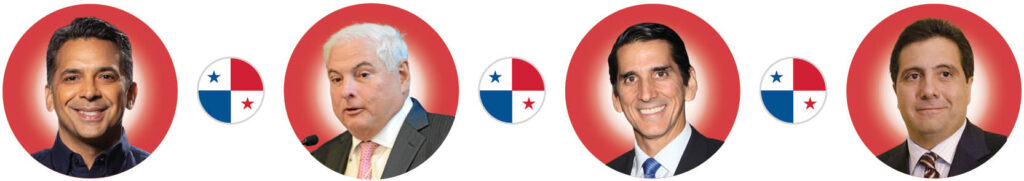

PANAMA: The Return of a Convicted President?

The historical alternation in power between Panama’s two traditional parties—Partido Revolucionario Democrático and Partido Panameñista—ended with Ricardo Martinelli’s election in 2009. Despite corruption allegations, Martinelli benefited from an economic environment (and contracted debt) that allowed him to invest in infrastructure—including building Panama City’s metro—which boosted his popularity. This led to the slogan robó pero hizo (he stole but delivered).

While polls favor Martinelli for the May presidential election, a major obstacle is Panama’s constitutional ban on individuals sentenced to more than five years in jail. In 2023, Martinelli was sentenced to over 10 years for money laundering, and the U.S. has barred his entrance to the country. Martinelli has denied wrongdoing. As of December, a challenge to overturn his conviction was pending. If the conviction is upheld, he will not legally be able to run.

Given his past harassment of opponents and media and allegations that he cooped judicial authorities, analysts fear his political comeback may jeopardize the rule of law in Panama and invite reprisals against those who pursued charges against him.

If Martinelli doesn’t run, the presidency is up for grabs. Having moved beyond the two-party system after Martinelli’s election, and the more recent permission for independent candidates to run, fragmentation makes it difficult to predict who could win and how they could govern.

In 2023, massive demonstrations took center stage as tens of thousands flooded the streets—the largest protests since the country’s return to democracy in the 1990s. The uproar was against the government’s attempt to renew a mining concession to a Canadian company, which was recently declared unconstitutional. While environmental issues were not a top voter priority, candidates’ mining ties could influence the electoral outcome.

Meet the candidates in Mexico’s 2024 election

MEXICO: Undermining Electoral Integrity

The June elections are critical for the future of Mexico’s democracy. They take place in a context of attempts by President López Obrador and his Morena party to undermine independent institutions, including the National Electoral Institute (INE). Tensions heightened after the Supreme Court struck down measures targeting INE’s personnel, elections monitoring capabilities and budget independence. The president’s attacks on the court, coupled with a proposal of a constitutional reform to elect judges by popular vote, raise alarms of democratic backsliding. They follow harassment of political opponents, independent media and civil society groups, alongside escalating militarization.

Nonetheless, López Obrador remains highly popular, partly due to his austerity measures, social policies, poverty rate reduction, and his perceived closeness to the people, fueled by his daily press conferences.

For the first time since 2000, when Mexicans voted to end 70 years of one-party rule, the state is actively supporting the ruling party’s candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum. Sheinbaum, Mexico City’s mayor and López Obrador’s political heir, will benefit from government resources and media access. Her main rival, Xóchitl Gálvez, faces the challenge of leading a diverse coalition. While either would be Mexico’s first female president, there is still uncertainty around the future of women’s rights, as neither candidate has done much to champion this cause.

While polls currently favor Sheinbaum, the margin of victory is unclear—and that will have a big impact on Mexico’s future. A decisive win in legislative elections for Morena could strengthen its hold on Congress, potentially perpetuating López Obrador’s populist project by further undermining checks and balances, if Sheinbaum does not clearly distance herself from López Obrador. Alternatively, a narrow victory for Gálvez raises questions about López Obrador’s acceptance of defeat.

Meet the candidates in the Dominican Republic’s 2024 election

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: Stability Favors the Incumbent

The ruling party, Partido Revolucionario Moderno, took office in 2020 with an anti-corruption agenda, following massive social mobilization after the Odebrecht scandal. Under President Luis Abinader’s administration, an independent attorney general was appointed, leading criminal investigations into former government officials and individuals close to former President Danilo Medina. Despite inflation and reduced growth rates, the country maintains relative economic stability. Abinader’s handling of the pandemic enhanced his popularity.

Abinader, who faces a divided opposition and is leading the polls, seeks reelection based on his anti-corruption initiatives, particularly appealing to voters in middle- and high-income urban areas. He has also urged the international community to address Haiti’s crisis, seemingly aiming to secure more support, including from the country’s right wing.

The outcome of President Abinader’s success in the first round in May remains uncertain. Regardless, the upcoming elections do not pose a major challenge to the country’s democratic stability.

Meet the candidates in Uruguay’s 2024 election

URUGUAY: Electoral Financing

Uruguay stands out as an example of democratic coexistence. Institutions serve as the channels for addressing citizen demands. Trust in institutions, including but not limited to political parties, sets the country apart from the rest of Latin America.

Despite an increasingly hostile rhetoric (by Uruguayan standards) in the incipient campaign, the electoral year—with a first round in October—and transition will likely transpire calmly. Candidates must articulate strategies to tackle structural challenges, including grave prison conditions, disparities in access to basic services, and crime. Observers should closely monitor the results of the June primaries, especially within the left-wing coalition Frente Amplio, as a closely contested vote is expected.

The increasing presence of organized crime in the country highlights the need to improve regulations on private electoral financing. Existing legislation lacks clarity on disclosing private donations expenditures, excludes reporting on private funding for primaries, and overlooks oversight for online campaign spending. Also, the electoral court’s limited capacity for effective oversight reduces the accountability process to a mere formality. At the time of writing, an imperfect bill with some improvements is pending.

Meet the candidates in Venezuela’s 2024 election

VENEZUELA: The Day After

As Venezuela’s presidential vote gets closer, efforts to facilitate elections that are as close to free and fair as possible are essential. They should align with the European Union’s 2021 electoral observation mission roadmap. Key measures include allowing disqualified candidates to run, enhancing separation of powers and judicial independence, and abolishing the comptroller general’s authority to strip citizens of their political rights.

Despite the opposition’s overwhelming election of María Corina Machado as their presidential candidate in the October primaries, she remains arbitrarily disqualified from running for office. In a country with no judicial independence, the government responded by prosecuting the primaries’ organizers and members of Machado’s team. Meanwhile, the government engages in political negotiations with opposition representatives on electoral conditions and a humanitarian agreement, but their successful implementation looks unlikely. Simultaneously, discussions with U.S. authorities focus on securing sanctions relief in exchange for certain concessions.

While sanctions relief and legitimacy from internationally recognized elections are potent tools to incentivize those in power to embrace a democratic transition, they are not standalone solutions for resolving Venezuela’s debacle. Analyzing how accountability for international crimes can serve as leverage will be essential.

Without a serious conversation about what the day after will look like for those in power, the 2024 election will not lead to a democratic transition—and may well be used by the Maduro government to legitimize a repressive regime.