BUENOS AIRES—In recent weeks, two starkly different visions of the future of the digital world emerged from the globe’s AI superpowers. These competing philosophies have put Latin America in an uncomfortable position between them. The region now faces a digital dependency trap that could determine its technological fate for decades.

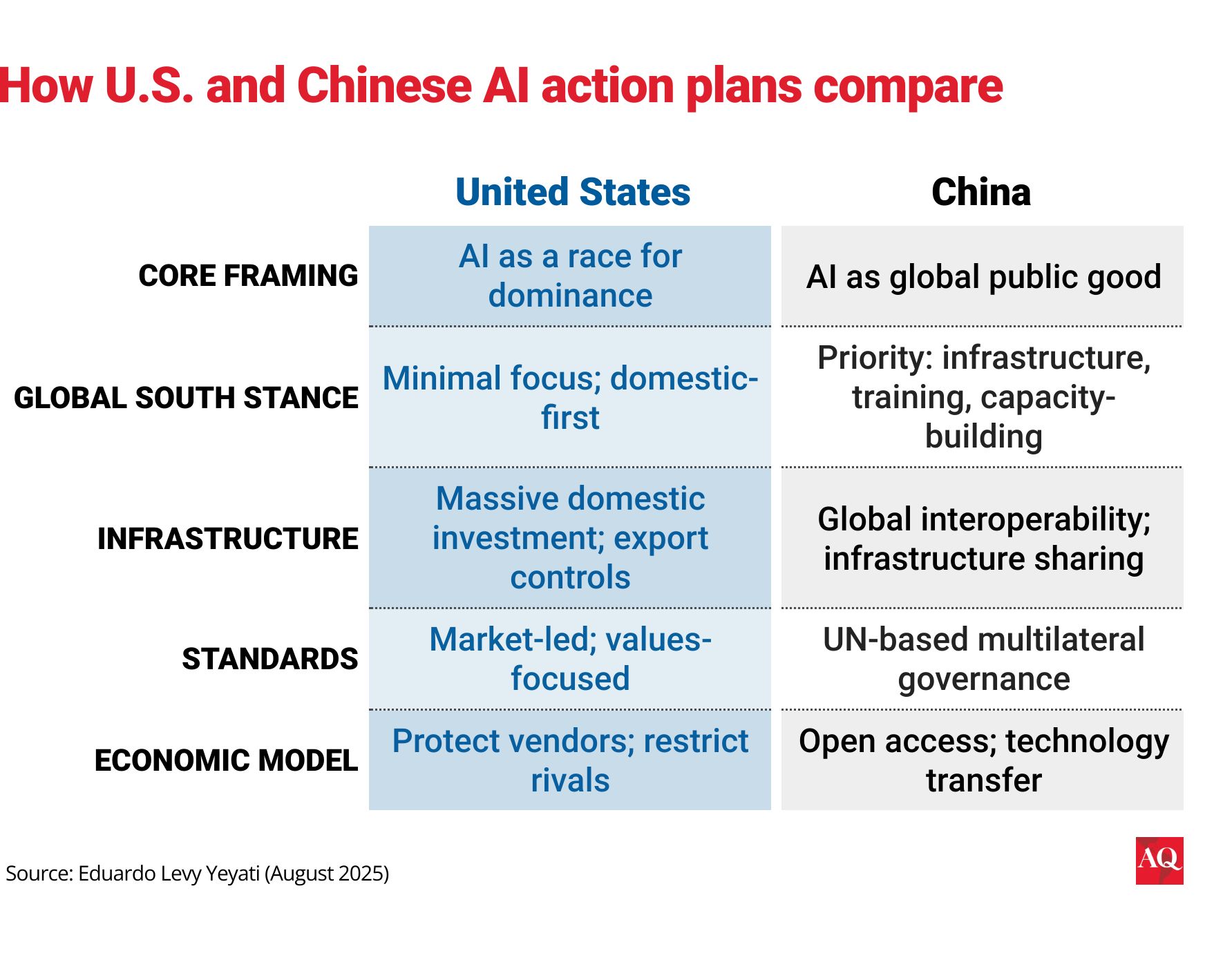

Last month, the Trump administration released “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” a comprehensive national AI strategy that frames artificial intelligence as a zero-sum competition where the U.S. must achieve “unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance.” An accompanying July 23 executive order launched an “American AI Exports Program” to export “full-stack” American AI technology packages.

The same month, China unveiled its “Action Plan on Global Governance of Artificial Intelligence,” positioning AI as a “global public good” that requires multilateral cooperation and emphasizing support for the Global South. According to Premier Li Qiang, artificial intelligence should become an international public good that benefits humanity.

For Latin American policymakers, these manifestos present what appears to be a binary choice. Choosing wrong could mean decades of technological dependency, limited sovereignty, and diminished prospects for indigenous innovation. The tension between the two paths, however, could offer the region an opportunity for growth.

Two diverging philosophies

The contrast between the American and Chinese approaches reads like a tale of two philosophies. The U.S. plan dedicates entire sections to removing regulatory barriers, building American AI infrastructure, and ensuring that allies adopt U.S. technology standards. It’s a digital Monroe Doctrine, establishing technological spheres of influence while systematically excluding adversaries through export controls and infrastructure dependencies.

China’s plan tells a different story. Where the U.S. emphasizes competition, China speaks of cooperation; where America focuses on dominance, China promotes “inclusive development” and explicitly calls for supporting developing countries in building their own AI capabilities. The Chinese document reads like a manifesto for technological multilateralism, promising infrastructure sharing, knowledge transfer, and UN-based governance frameworks that give smaller nations a voice. However, although the Chinese model and the emergence of DeepSeek could offer accessibility, Latin American nations adopting it wholesale risk swapping one form of technological dependence for another.

Consider Brazil’s dilemma. The country has already developed a sophisticated AI ethics framework and hosts world-class research institutions like CPQD. It largely depends on U.S. cloud services for much of its digital infrastructure but also welcomes Chinese investment in telecommunications and manufacturing. President Lula da Silva’s government must navigate U.S. trade and security pressures that favor U.S. tech integration with Beijing’s attractive infrastructure financing, all while trying to preserve space for Brazil’s own technological development.

Mexico faces more direct pressures: Its proximity to the U.S. limits flexibility. Imagine trying to adopt Chinese AI standards while sharing a 2,000-mile border with a country that views such adoption as a national security threat. Yet Mexico’s manufacturing base still relies on Chinese supply chains, and its growing digital economy needs all the technological partnerships it can get.

Regional coordination as a third option

The binary choice between the two plans may be a false one. Just as the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War allowed countries to benefit from both blocs without full subordination to either, Latin America’s best strategy may be digital non-alignment: a careful balancing act that preserves technological sovereignty while accessing the benefits of both ecosystems.

Some countries are already putting this into practice. For example, Chile positions itself as a regional digital hub while carefully managing relationships with both technological powers. The LatamGPT initiative illustrates this balance. Led by Chile’s CENIA, it’s an open-ish project where training data, evaluation, and roadmaps are controlled by regional institutions. Its infrastructure is diversified, combining U.S. hyperscalers like AWS and Microsoft, with Huawei cloud and data centers, and Asia-Pacific connectivity via the new Humboldt trans-Pacific cable with Google. The same applies to Brazil’s $4 billion, four-year AI Plan, which hedges the U.S.–China rivalry by pushing tech sovereignty: domestic models and compute, public financing (FNDCT/BNDES), and rule-setting via the G20 and the United Nations.

Regional coordination offers Latin America’s strongest path forward. Rather than each country negotiating separately with AI superpowers, the region could develop shared standards that prioritize interoperability and prevent vendor lock-in. The Pacific Alliance, or similar regional bodies, could create AI frameworks that reflect Latin American values rather than importing governance models designed elsewhere.

Consider what this might look like in practice. A Latin American AI consortium could pool resources for research and development, sharing costs and expertise across borders. Regional data governance frameworks could protect sovereignty while enabling innovation, and joint procurement standards could prevent any single government from being pressured into exclusive technology partnerships.

Brazil, with its technical sophistication and market size, could serve as an anchor for such regional cooperation. Mexico’s manufacturing expertise and Central America’s growing tech sector could provide complementary capabilities. Argentina’s research institutions and Chile’s digital infrastructure could round out a regional ecosystem capable of competing globally while maintaining independence.

The cultural dimension

Cultural attitudes to automation can be as important as technical expertise in shaping how new technologies are adopted. Latin America’s approach to AI adoption could be more human centered than either the American emphasis on market efficiency or the Chinese focus on state coordination. The region’s strong traditions of community organization, cooperative economics, and social solidarity could inform AI governance models that prioritize human welfare over pure technological progress.

This link is already visible: Brazil’s General Data Protection Law guarantees the right of review for automated decisions and Open Finance mandates consent-first data sharing; Chile’s updated AI Policy is being built through public consultation; and Argentine court rulings have suspended Buenos Aires’ facial-recognition system on due-process and privacy grounds.

This cultural dimension offers Latin America a competitive advantage in developing AI applications that could face less social resistance. While U.S. and Chinese companies race to build more powerful models, Latin American developers might focus on AI that feels trustworthy and aligned with regional values, creating a market niche that neither superpower can easily replicate. It’s important to note, however, that culture is a compass and does not operate on autopilot: these positive outcomes will ultimately hinge on procurement, data rules, and incentives.

The clock is ticking

Time is running short for strategic action. As both the U.S. and China accelerate their efforts to lock in technological partnerships, the space for autonomous decision-making is narrowing. Countries that don’t act soon may find themselves choosing not between competing visions of AI governance, but between whatever options remain after the major powers have divided the technological landscape between them.

Regional leaders must recognize that the choice between American and Chinese AI governance models is itself a trap. Latin American societies have a say in determining how these transformative technologies get developed and deployed in their own countries.

That’s where real opportunity lies: in a Latin American approach to AI that serves the region’s development needs while preserving the technological sovereignty that makes true choice possible.