SÃO PAULO — Netflix’s Maid is on track to become the most-watched miniseries in the platform’s history, with an estimated viewership of some 67 million people and nearly unanimous rave reviews. Its themes of rising inequality and domestic violence have clearly struck a nerve around the world — including here in Brazil.

As a political science professor, I was intrigued by several aspects of the series, which focuses on a mother and her toddler fleeing their abusive home. The series shows a side of the United States hardly ever seen in Hollywood — namely, the peculiarities of American poverty, in which people may not have access to housing or even food, but still own relatively nice cars and iPhones. I did not know that the U.S. may have two and a half times more homeless people as in Brazil (580,000 as opposed to 220,000, according to official figures), or that Walmart parking lots were spots where people often sleep for the night — facts that indicate housing is far from a public good in America.

Another striking revelation is supplied by the show’s insight into the nuts and bolts of the U.S. welfare system, something many Brazilians did not even know existed. That millions of Americans rely on governmental food stamps and rental assistance programs — drowned in endless red tape and inscrutable forms — provides an interesting counterpoint to the often praised U.S. labor system, dynamic but extremely deregulated and unprotected, based on low wages.

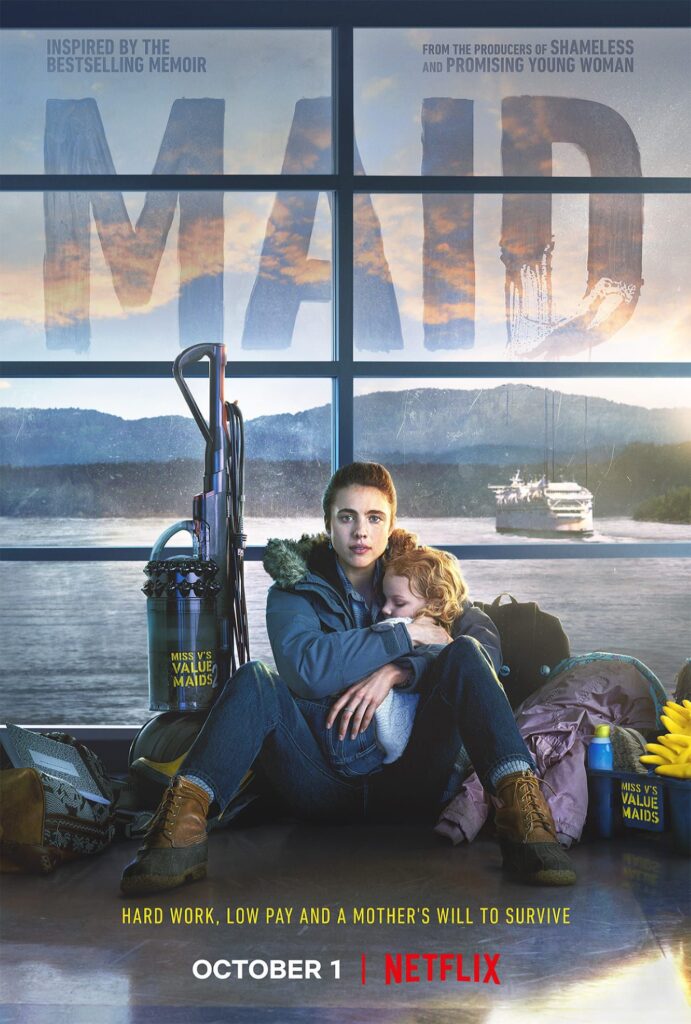

Maid

Directed by John Wells, Nzingha Stewart, Lila Neugebauer, Helen Shaver, and Quyen “Q” Tran

Starring Margaret Qualley

United States

Another main theme of Maid is domestic violence, to which, unfortunately, Brazilians are no strangers. Contradicting a common assumption that this violence only takes place between couples, the series sheds light on violence against women and girls in broader family contexts. These situations are not unfamiliar in my country: A recent survey by the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety reveals that about one in every four women over 16 was a victim of physical, psychological, or sexual abuse in 2020 alone — and half of the cases took place at home.

Maid’s third lesson relates to race relations. The series follows recent releases like Hillbilly Elegy in exposing the struggles of a decadent white lower middle class. But while the film adaptation of the J.D. Vance book addresses poverty across the urban-rural divide, highlighting the downfall of small industrial towns across the rust belt, the Netflix production illuminates growing hardship in suburban regions, outside the poor Black and Latino communities typically shown (and often stereotyped) in movies.

One interesting subtlety of the show lies in that, while the main characters are white, others in powerful positions — an affluent client, a judge, an owner of a cleaning service, a well-off friend, a woman who runs a domestic violence shelter — are people of color. This is a testimony to the possibilities of upward mobility in America, but it also hints at the racial resentment that motivates part of the country’s impoverished middle class.

Netflix’s Maid is not only a beautifully produced series that alternates tear-jerking moments of utter despair with touching outbursts of love and hope. It also has much to say to Brazilians about the languishing side of American society — even pointing to some unlikely virtues in our own society. From pioneering specialized women’s police stations dating back to 1985, to an ambitious nationwide conditional cash transfer program and a universal healthcare system, Brazil, with all its flaws, has made strides in protecting the most vulnerable. Despite recent setbacks in my country, the stark contrast with the reality shown in this series reminds us that Brazil’s social protection net remains something to be proud of.

—

Casarões is professor of political science and international relations at Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo/FGV