This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on A (Relatively) Bullish Case for Latin America

Three portraits dominate a room in The Upside-Down World, the latest exhibition by Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki. They imitate an artistic style from Peru’s colonial past: Each portraying an Indigenous person or profession, they are intended to categorize colonial society and instruct the viewer.

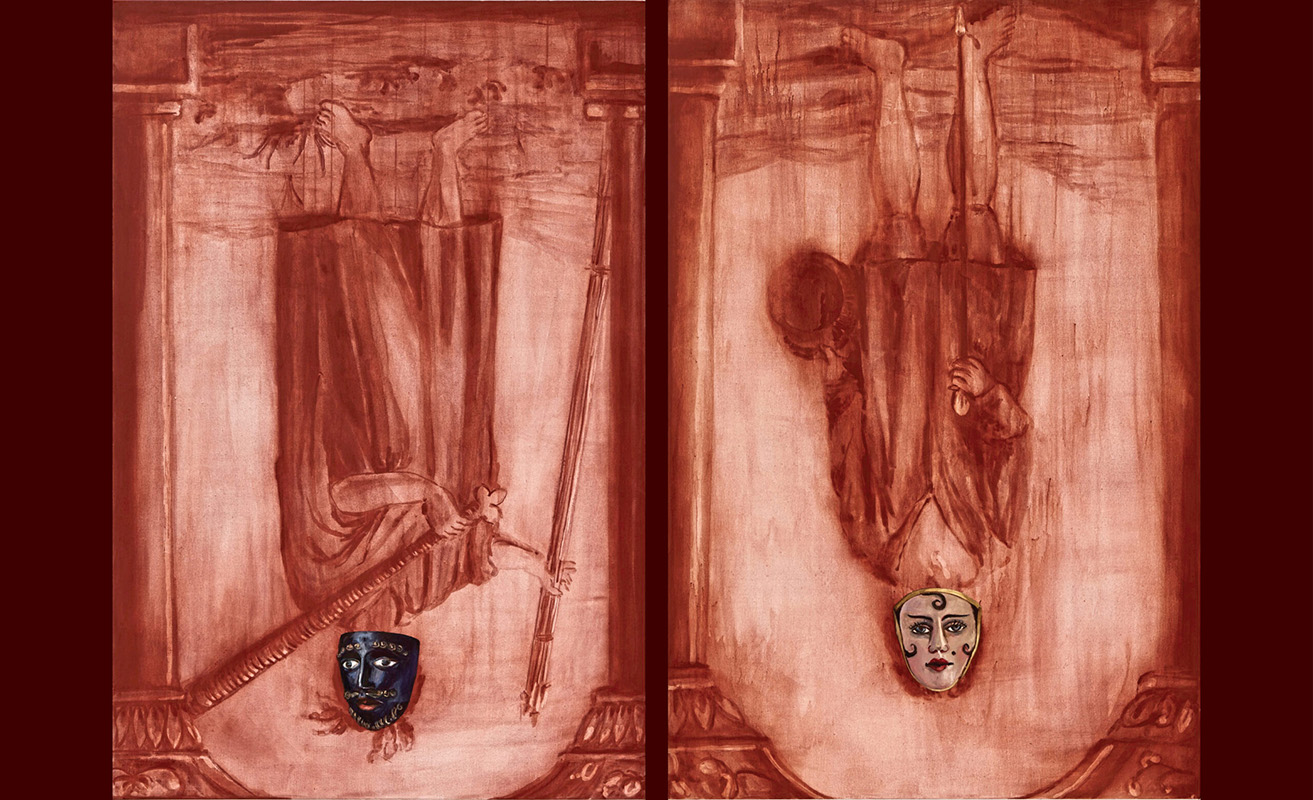

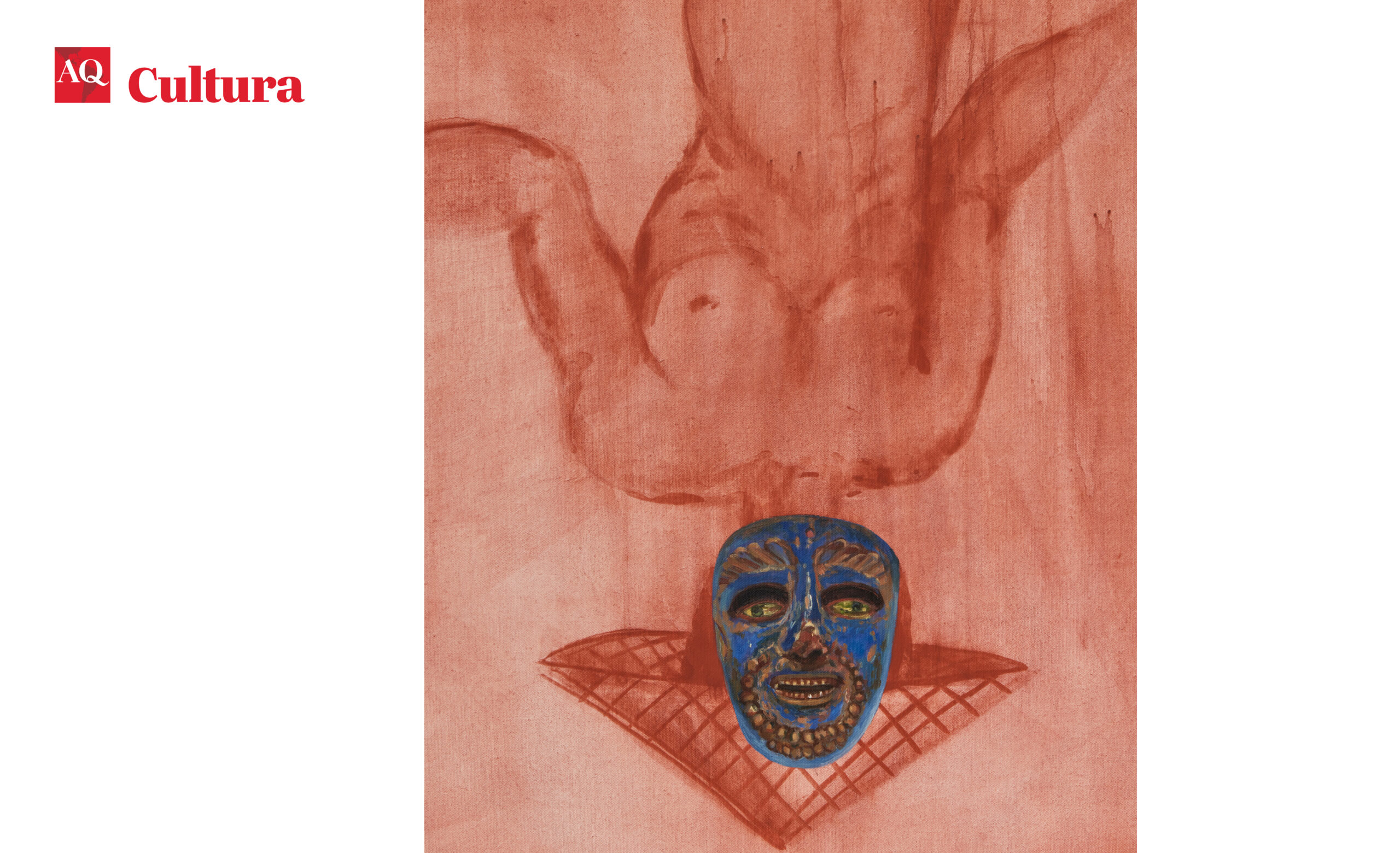

But in Gamarra Heshiki’s version, the portraits hang upside-down—and their faces have been painted over with colorful Peruvian dancing masks, testaments to an Indigenous culture that has survived to the present day in traditional festivals and religious celebrations. These unexpected additions pop out against the ghostly hues of the portraits, symbolizing the Peruvian present inverting and contesting depictions of its past.

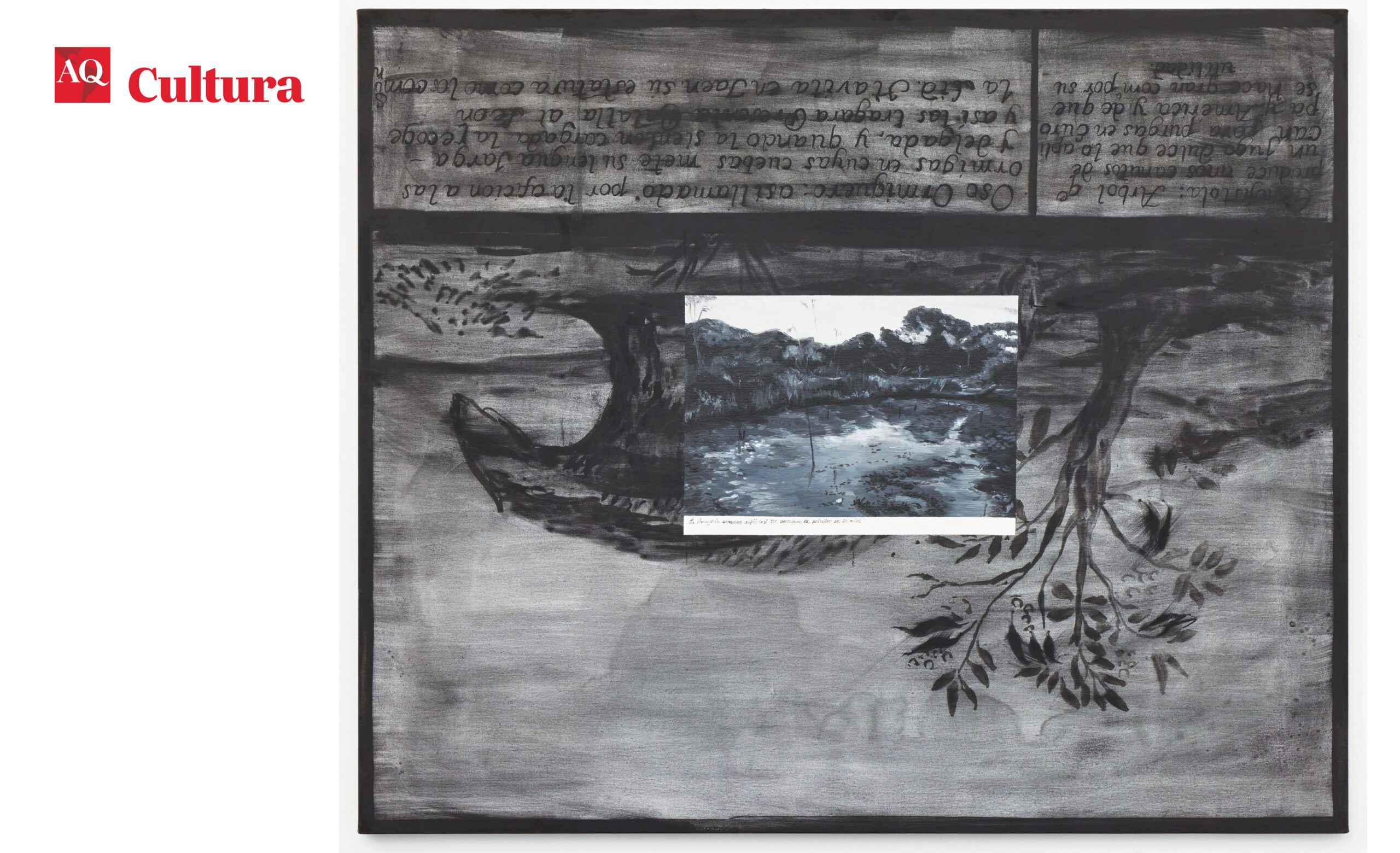

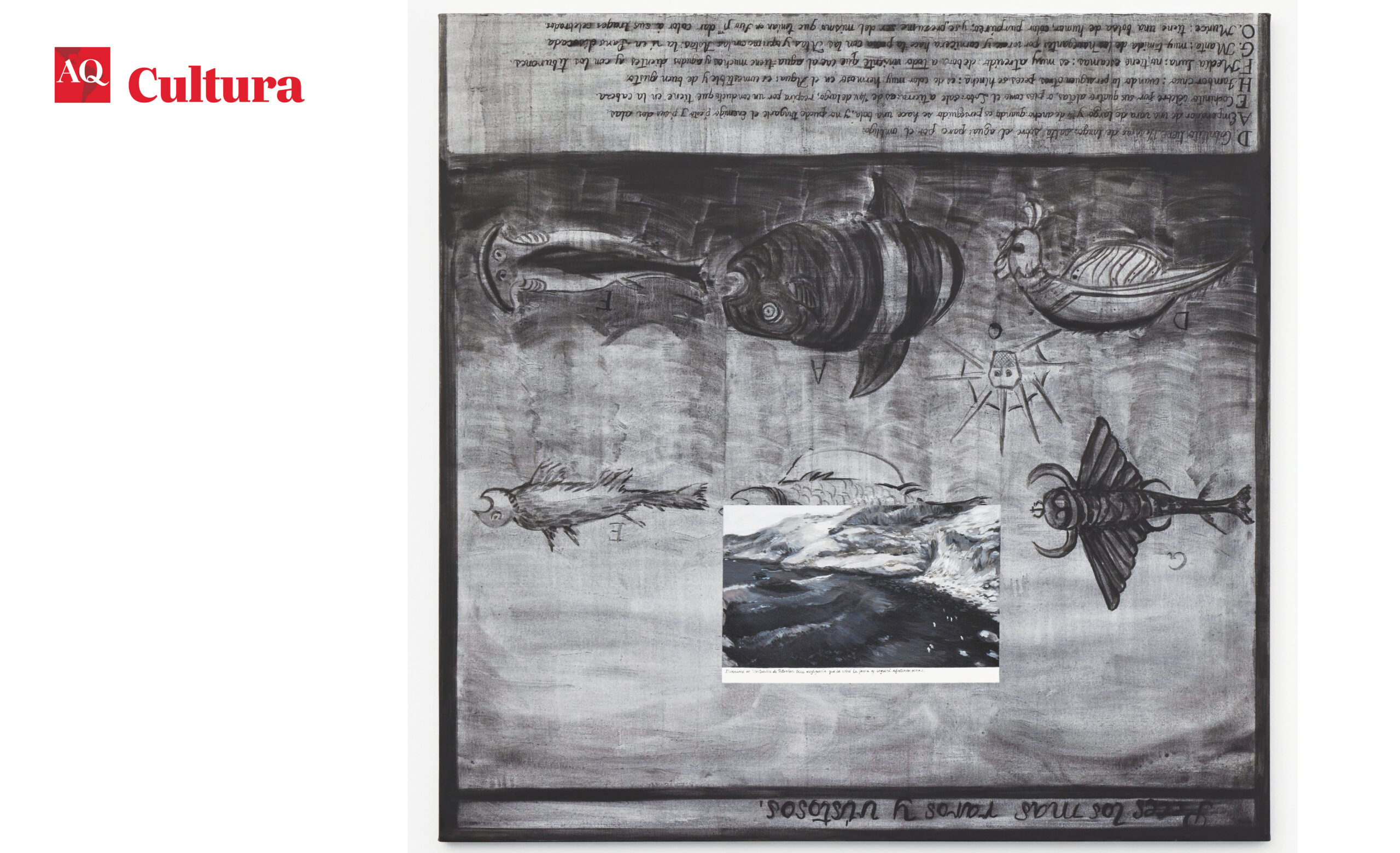

The Upside-Down World takes its title from a historical report by Quechua nobleman Guamán Poma de Ayala about the sorry state of the colonial-era Peruvian Viceroyalty. In the exhibition, Gamarra Heshiki literally inverts colonial iconography to question the principles that, in her view, have brought the country to its current state: “permanent growth, linear progress, nature as the producer of goods.” To that end, colonial-era didactic drawings, labeled and organized into grids of local plants, animals, and native populations, are turned upside down and juxtaposed with archival photos of petroleum spills in the Peruvian Amazon.

Lately, these spills have become a common byproduct of the Peruvian petroleum business, which is largely based in the Amazon: In 2022, an average of one spill was recorded every three days, including an especially disastrous accident that covered over 35 square miles (100 square kilometers) of sea and shoreline with oil slick, devastating residents and local wildlife. Amid continuing cleanup efforts, there’s a mounting sense of dread over the long-term effects of contamination. That dread is reflected in one of the rooms of The Upside-Down World featuring a series of fabric panels on a gradient from yellow to black, each with a tear in the center revealing a pitch-black layer beneath. This tear seems to gradually darken the larger work, until the final piece in the series almost matches it in blackness.

El mundo al revés (The Upside-Down World)

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki

80m2 Livia Benavides, Lima

Support for oil extraction in the Amazon has faltered as its baleful side effects have become more obvious, but it’s regarded as crucial by a government increasingly concerned with self-sufficiency and tempted by the prospect of exports at a premium amid a global energy crisis. Meanwhile, citizens of Peru’s relatively populous (and prosperous) coast have begun to express concern over spills reaching their shores, reigniting a debate that had simmered for decades.

As Gamarra Heshiki signals a break with the idealized colonial past and its precepts, she does so in the context of a revived national fondness for Spanish cultural heritage. Rafael López-Aliaga, the current mayor of Lima, has praised Spanish right-wing party Vox. In the face of an emboldened “Hispanicist” movement that would reclaim colonial symbols as contemporary icons, an explicitly anti-colonial movement is rising to meet it.

Gamarra Heshiki’s concealment and defacement of colonial iconography indicates a sense of urgency. The black sheen of petroleum, reinterpreted as an encroaching darkness, appears constantly in these portrayals of a prosperity myth gone wrong. With the deflation of Peru’s commodity boom and a seemingly endless governance crisis exacerbated by one of the world’s longest pandemic lockdowns, citizens are less willing to overlook the negative externalities of resource extraction. The smoldering tensions that led to outbursts of deadly violence in the Amazon over the last 20 years remain unresolved. Meanwhile, a flagging economy forces authorities to revive Hispanic nostalgia, import “culture war” issues from abroad and relitigate a checkered national past. Amid this great panoply of social and political disarray, The Upside-Down World is both a clear-eyed indictment of our ongoing predicament and a solemn warning of the disasters that still await us.

—

Gallo is a lawyer and art history writer based in Lima.