This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the Trump Doctrine

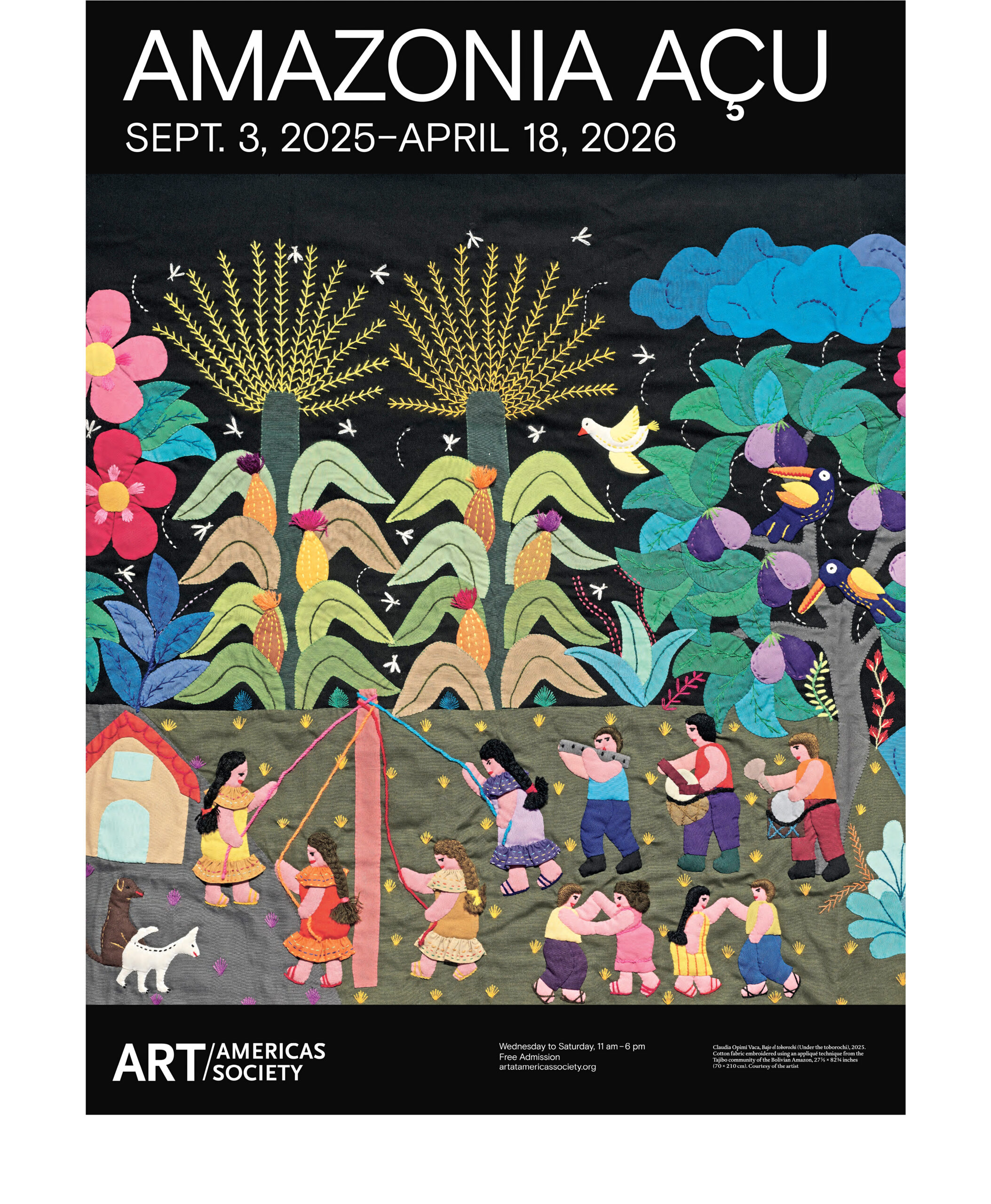

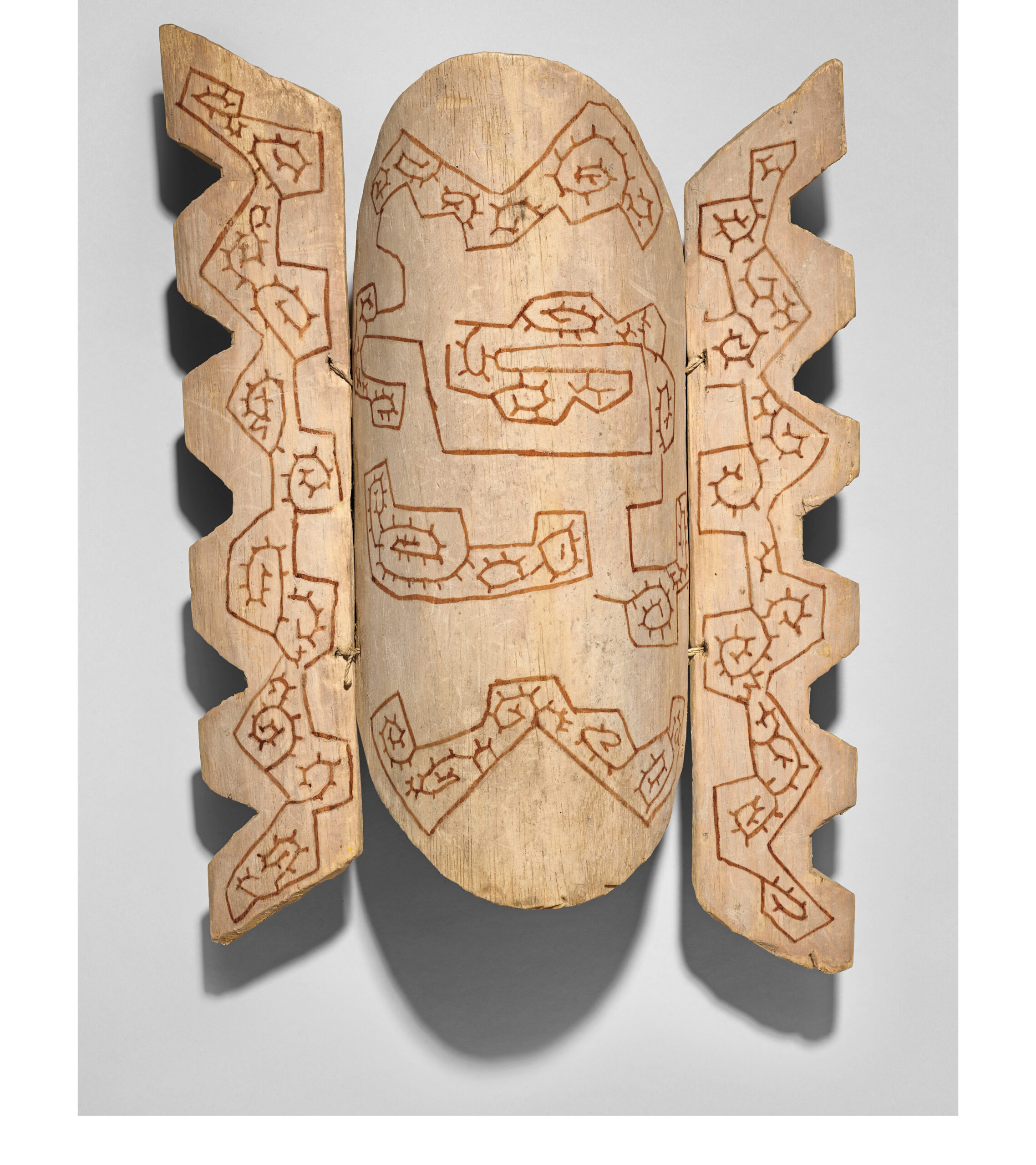

Amazonia Açu, on display in New York

by Carolina Abbott Galvão

Conversations about the Amazon tend to center on the physical world: the practical or the scientific. When people talk about the rainforest, they talk about illegal logging, water stress, droughts or deforestation. They talk about rivers, plants or poisonous frogs. They don’t often center the people who live there.

Two new exhibitions, one in New York and another in Paris, offer a different, less stereotypical view of the region, showcasing the creativity of its residents. The message here is clear: The Amazon is undeniably a site of political and environmental relevance. It is definitely a place we should study and protect. But there’s more to it than just the science. In addition to being biodiverse and ecologically significant, the region is also home to artistic traditions of its own, inhabited by complex societies and culturally rich civilizations that not only lived in harmony with nature but also actively shaped it without destroying it.

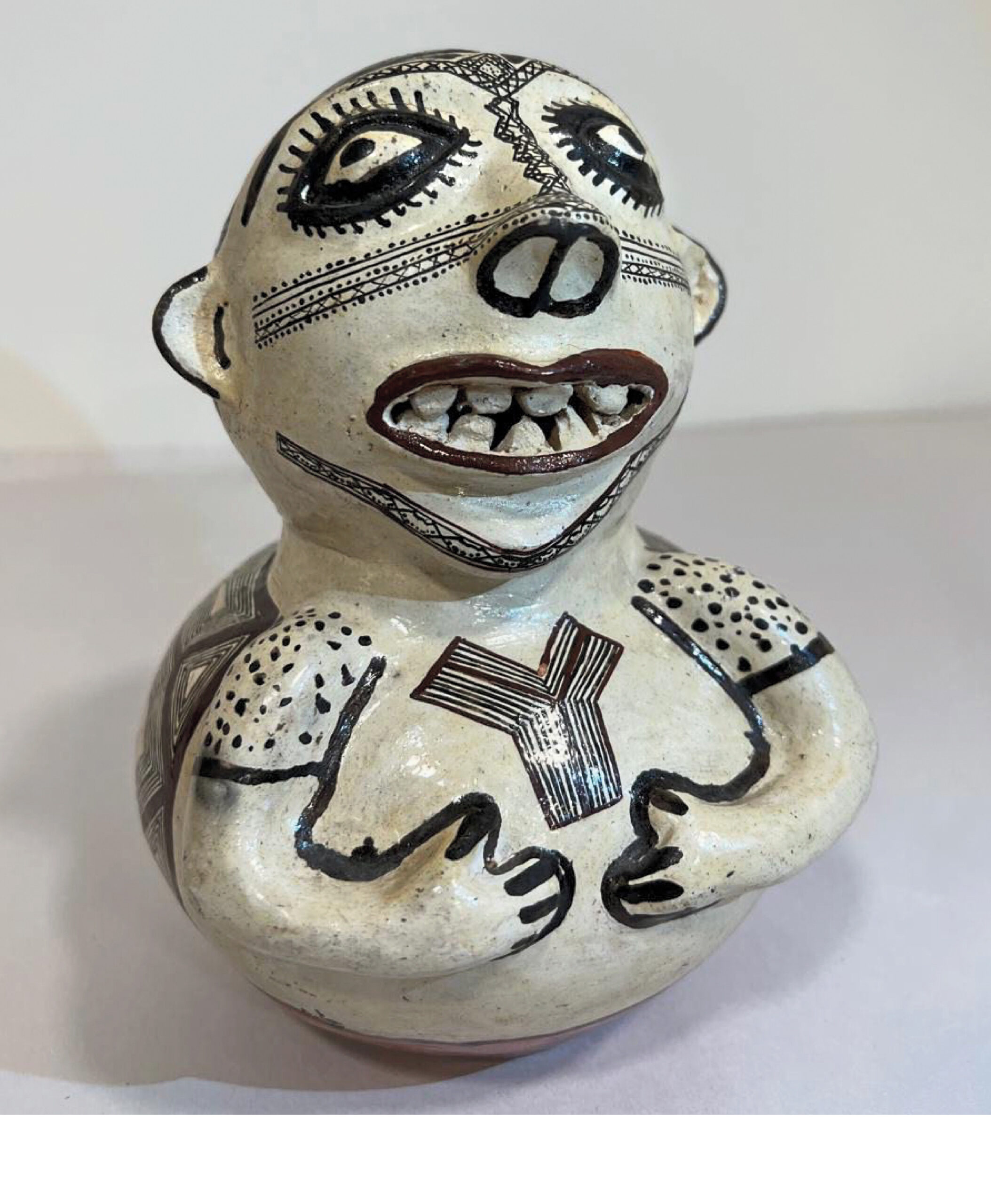

In the exhibition Amazonia Açu, on view through April 18, 2026, at Americas Society in New York, the curators, who come from the nine countries that make up the region, selected works that span time periods and mediums. Here, paintings hang next to baskets, and videos play close to ceramic pieces and sculptures. No art form is given priority over another. No piece resembles the other. And so the term “açu”, Tupi Guaraní for “expanding,” aptly describes the show, which quietly coalesces Western distinctions between art and craft, old and modern. It’s easy to picture the Amazon as a monolith, but the sheer diversity of techniques and the various stories on display here prove that there is much more to the region than meets the eye.

Amazonia Açu, on display in New York

In Sara Flores’ textiles, geometric lines curve around and into each other like gnarled tree branches or the lines on a subway map. In Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe’s cotton-paper books, colorful snakes twirl around leaves in whimsical S-shapes. PV Dias takes a different approach, overlaying digital paintings of Amazonian objects and people onto photos of urban centers to highlight the tensions between the two sites.

Explorations of the tension between these two worlds also feature prominently in Colectivo Tawna’s work. Established in Ecuador in 2007, the film collective brings together filmmakers and visual artists who want to dream of a better future for the region. The photographs featured in the exhibition come from Ñuka Shuti Man, an installation piece wherein the collective’s co-founder, Sani Montahuano, and her sister pay tribute to their mother, Carmelina Ushigua.

As a young girl, Ushigua was forced to marry and move to the city from an Amazonian town. In the piece, Montahuano attempts to grapple with the things her mother lost and tries to understand the worlds she inhabited. One especially striking image depicts the three long-haired daughters sitting in a line, almost melting into each other, as the forest looms behind them.

As a Sapara woman living between the city and the forest herself, taking pictures helped Montahuano understand her story, as well as her mother’s, and “the messages she carried” with her. In a way, many of the pieces in the exhibition feel like messages too, only they are the kind that never fully arrive. In the pale glow of the gallery, these artworks live in a separate third space of sorts. Like Montahuano, they exist not in the city, nor in the forest, but rather somewhere in between.

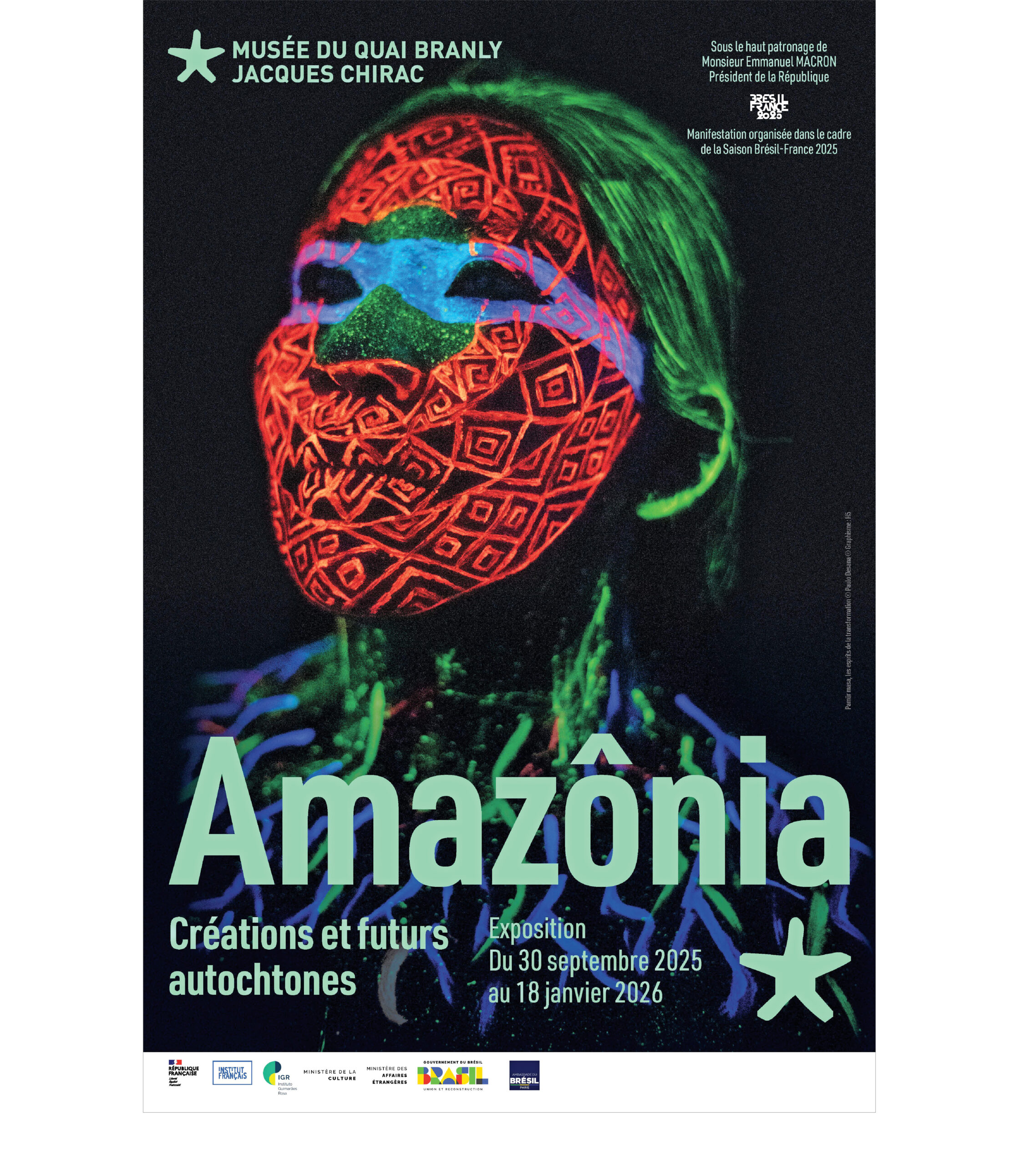

Amazônia – Indigenous Creations and Futures, on display in Paris

by Andrei Netto

In Paris, the exhibition Amazonia – Indigenous Creations and Futures, running through January 18 at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, depicts the Amazon not as a pristine wilderness in need of preservation, but as an ecosystem that was home to millions of inhabitants who spoke hundreds of languages and maintained intricate networks of migration and knowledge exchange. The colonialist idea of “savage” peoples—seen as both innocent and ignorant—gives way to the reality of sophisticated, multiethnic communities with complex worldviews and a relationship with nature where humans are not at the center but one element connecting with other species and dimensions through ritual practices.

The curators, Brazilians Leandro Varisio, deputy director of the museum’s Research and Education Department, and Denilson Baniwa, an artist, curator and Indigenous rights advocate, showcase the traditional knowledge produced by Amazonian civilizations— a vast body of understanding that shares some common ground with Western science, including empirical observation.

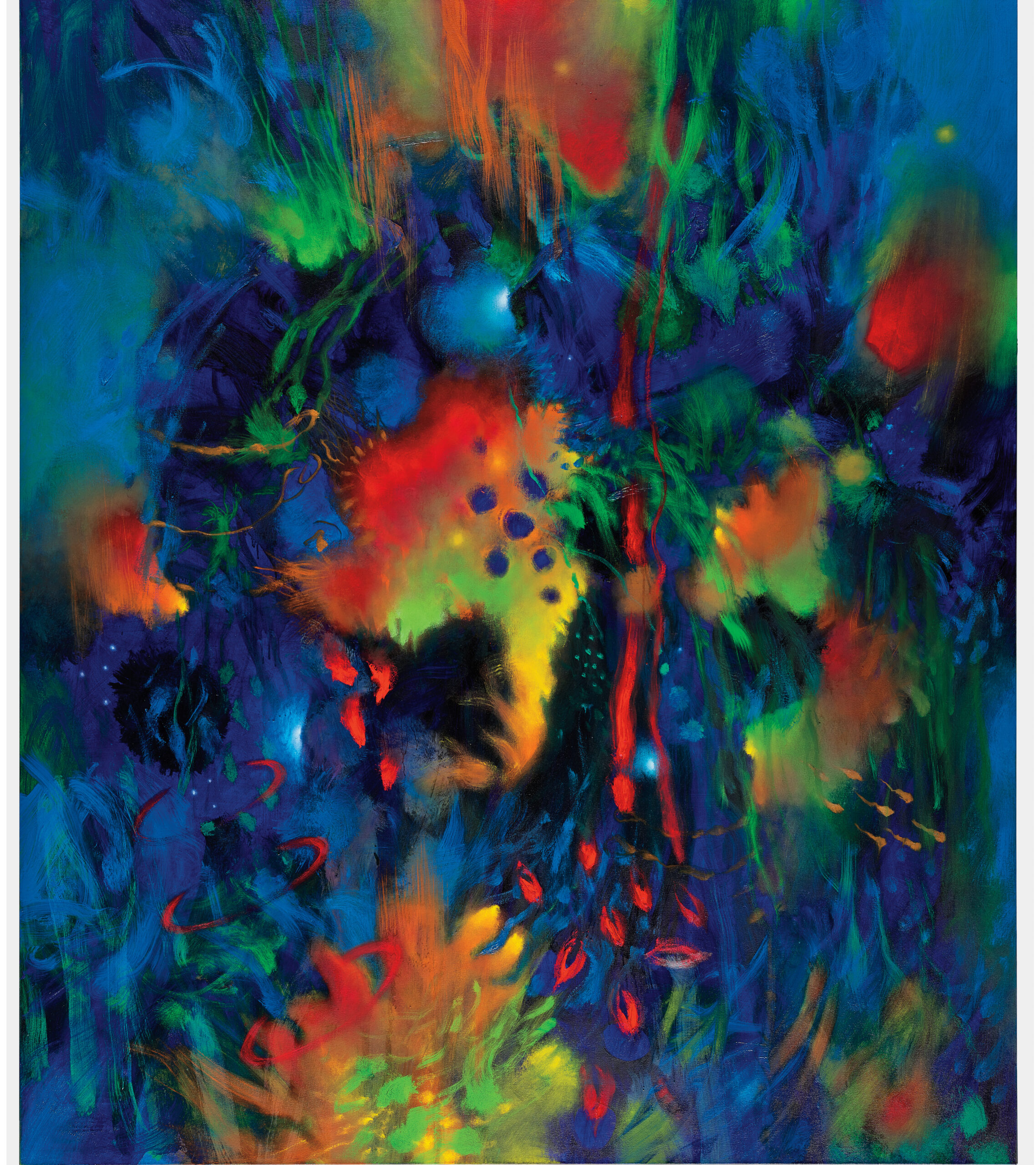

The exhibition then projects possible futures for the Amazon and its civilizations, grounded in values beyond economic growth and wealth accumulation, which have depended on environmental degradation.

Varisio and Baniwa present archaeological artefacts, jewelry and objects from Indigenous communities alongside photo essays, documentaries and contemporary artworks by artists including Paulo Desana, Brus Rubio Churay, Rember Yahuarcani and Baniwa—an assertion that these cultures remain vigorous, creative and present in regions we continue to devastate.

While acknowledging the nine Amazonian countries—Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana—the curators go beyond political boundaries. The Amazon, they say, functions as a region without borders, where people have historically moved, formed networks, and developed subsistence strategies in harmony with the forest through wise agroecology.

Amazonia, on display in Paris

The exhibit steers clear of dwelling on the ongoing environmental catastrophe, instead making an indirect reference by noting that these forest civilizations, their languages and cultures, face new threats from human activity and the climate crisis.

These exhibitions reveal a common truth that anthropologists and archaeologists have been writing about and that Indigenous peoples have long known: that the forest is a managed habitat rather than an untouched wilderness, and its civilizations are far more complex than previously imagined by Western cultures.

They may also reveal more about those audiences than about Indigenous communities themselves. Five centuries after colonization, European and American publics are finally understanding that our civilization is merely one among many—and not necessarily the wisest.