In October 1858, U.S. President James Buchanan dispatched the largest naval deployment in U.S. history to date: 19 warships, sent not to the high seas, but to the landlocked nation of Paraguay. The force sailed in response to a previous Paraguayan attack on the USS Water Witch, a vessel charting the inland Paraguay-Paraná river system.

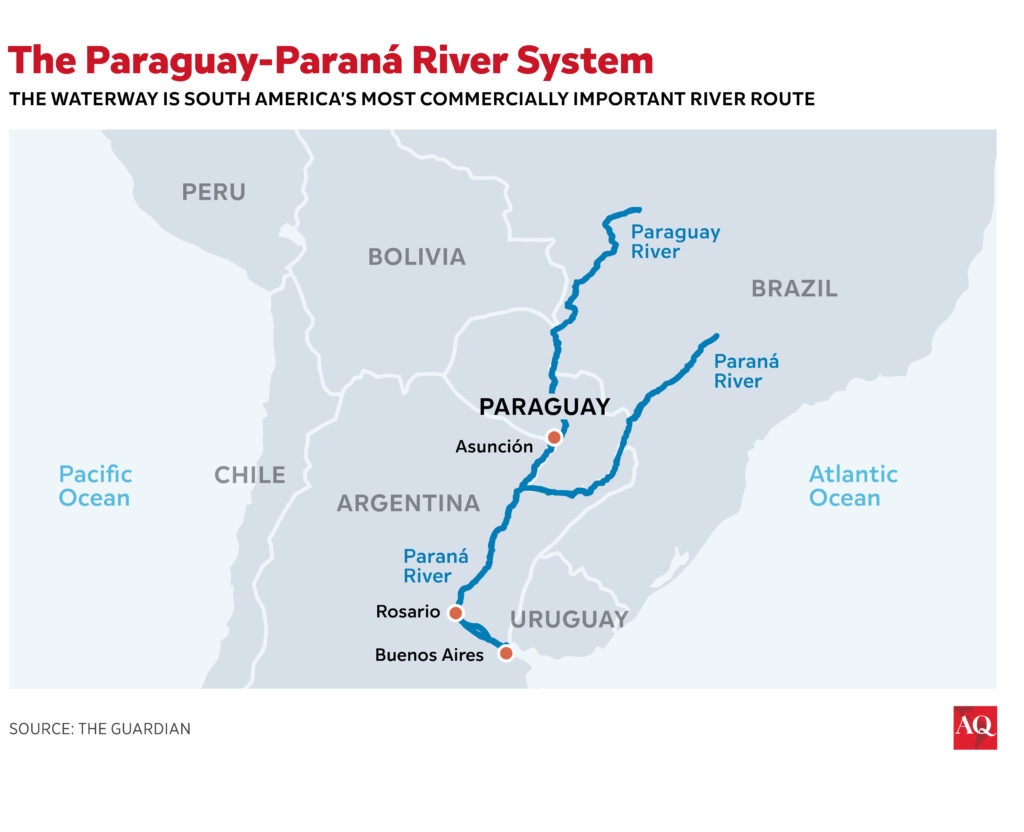

This waterway then largely fell off Washington’s radar, overshadowed by more pressing chokepoints such as the Panama Canal and emerging Arctic sea lanes. However, recent events are transforming South America’s most commercially important river route—stretching over 2,000 miles and connecting more than 100 inland ports—into a subregion where the U.S. and China are competing, driven by the urgent need to secure commodities and minerals.

Referred to as the “Hidrovía,” this waterway encompasses the entire Paraguay River, from its headwaters in Mato Grosso, Brazil, to its junction with the Paraná River on the Paraguay-Argentina border, and then the Paraná’s southern run through Argentina to Uruguay and the Atlantic. Now, with a surge of infrastructure projects along its banks, the corridor is reemerging as a vital, contested axis for regional trade and security.

Traffic is growing so quickly that the Board of Trade of Rosario (BCR)—the Paraná’s primary inland grains port—projects that the volume of cargo transported on the waterway could double by 2035. The waterway already moves more than 100 million tons annually, including soybeans, corn, iron ore and critical minerals. The BCR forecasts that by 2030, countries in the Paraguay-Paraná river basin will supply 40% of the world’s grain, along with natural gas from Vaca Muerta shale, as well as lithium and copper from northwestern Argentina.

Argentina and Paraguay are planning major dredging projects to deepen their river channels and accommodate larger barge convoys, which already carry upwards of 85% of Paraguay’s trade and around 80% of Argentina’s exports. Both investment and foreign interest are ramping up; China and the U.S. are maneuvering for influence along the corridor, as are transnational criminal organizations, for Andes-to-Atlantic drug trafficking and other illicit activity.

Investment and drought

Infrastructure demand is driven by years of underinvestment and worsening drought. Ships reportedly run aground about once a month on Argentina’s Paraná, forcing vessels to reduce cargo. Last year, the Paraguay River reached record lows, causing an estimated $300 million in losses to Paraguay’s economy and compounding the costs from similarly severe droughts in 2020-21.

This combination of vulnerability and strategic value is attracting external actors such as China. Beijing continues to expand its access to South American agricultural and mineral resources, as seen in the recently inaugurated $3.5 billion Chancay port in Peru and planned rail links through Brazil. In March, Argentine lithium carbonate destined for China started shipping through Rosario, which is expanding mineral storage facilities to meet demand.

Chinese firms are looking to gain more ground. In February, Javier Milei’s administration suspended the concession of a 30-year dredging contract due to apparent irregularities, as only one firm, from Belgium, had submitted a bid. An earlier contender, Shanghai Dredging Co.—a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), affiliated with several U.S.-sanctioned entities—could reenter the bidding process if new terms permit state-owned firms to participate.

Yet Argentina’s main-trunk dredging project is just one piece of a broader push. Upriver, Bolivia seeks to upgrade its Puerto Busch port, while Brazil is proceeding with dredging plans for the Corumbá to Rio Apa stretch of the upper Paraguay, despite environmental concerns over severe consequences for the Pantanal, the planet’s largest inland wetland and a vital biodiversity hotspot. Similar concerns have been raised regarding Argentina’s dredging. These projects can be expected to become environmental flashpoints in coming years as climate change, deforestation, and environmental degradation continue to reinforce each other’s worst consequences—and stress freshwater resources.

Paraguay’s pivotal role

Paraguay is situated at the heart of the river system, and despite a population of just over six million, operates the world’s third-largest fleet of river barges, according to its commerce ministry. Here, strategic competition goes beyond state actors. Paraguay’s position between Brazil and Argentina makes it a transshipment corridor for regional drug trafficking, with groups such as Brazil’s Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) increasingly using river ports like Villeta, less than 20 miles (30 km) from Asunción, to move Andean cocaine to Atlantic markets. With limited state capacity, Paraguay struggles to counter these flows, which fuel money laundering networks flagged by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

Under the current Trump administration, signs point to recalibrated cooperation. Earlier this year, Paraguay acquired its first aerial radar system via the U.S. Foreign Military Sales program, improving surveillance of remote regions. In March, the DEA and Paraguay’s anti-drug agency (SENAD) renewed their partnership after earlier reports of a rupture. Washington could build on this by addressing port vulnerabilities along the river—such as deploying U.S.-built container scanners like those previously donated by Taiwan.

There is also scope for broader engagement. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) previously proposed dredging and infrastructure studies for the river stretch between Concepción and Asunción—a project likely to receive renewed support from Paraguay’s pro-U.S. president, Santiago Peña. Downstream, Milei’s strong alignment with Washington presents a rare opportunity for coordinated action along the river corridor from Asunción to Buenos Aires—a prospect endorsed by Paraguay’s top soy and grain exporters association and supported by a new USACE agreement with Argentina’s General Ports Administration to improve navigability.

Moreover, Washington appears to be taking notice of Paraguay’s outsized importance. Secretary of State Marco Rubio met with President Peña in January, following his 2024 trip as the first sitting U.S. senator to visit Paraguay in four decades. In May, Rubio called for U.S.-backed AI investments in Paraguay, citing surplus energy from the upper Paraná’s 14-gigawatt Itaipu Dam.

U.S. engineering firms with expertise on the Mississippi River, which shares key characteristics with the Paraguay-Paraná, would be well-placed partners. Capital from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) could catalyze private sector investment, building on DFC support for port projects elsewhere in Latin America.

Paraguay is already attracting investor interest. The IMF expects the country’s GDP to grow 3.8% this year and 3.5% from 2026 through 2030. Economic activity is clustering around river hubs like Villeta and Concepción, home to new fertilizer plants, rice farms, and Paracel’s planned $4 billion pulp mill—slated to be Paraguay’s largest-ever private investment. Exploration is also underway for lithium, silicon, and uranium.

Intensifying competition

Still, a U.S. strategy for the Paraguay-Paraná corridor will face headwinds. In addition to Beijing’s broader aim to secure South American commodities, its diplomats are targeting Paraguay given its diplomatic ties with Taiwan—the last such case in South America.

Chinese demand for South American commodities, expanding export markets in Asia and the Middle East, and growing prospects for an EU-Mercosur trade deal are all raising the Paraguay-Paraná’s geopolitical profile. But unlike in 1858, when the U.S. sent gunboats, today’s contest demands diplomacy, technical know-how, and tailored investment. Paraguay, via its namesake waterway, offers Washington a win-win port of entry to shore up its regional influence—if the U.S. acts before the current of global competition goes the other way.