RIO DE JANEIRO – The U.S., Latin America and Europe might seem worlds apart when it comes to a common agenda. Just last month, French President Emmanuel Macron called for an end to talks between the EU and Mercosur on a long-awaited trade deal that now looks moribund. And recent global conflicts like the wars in Ukraine and Gaza have seen many leaders in Latin America defy the stances taken by the U.S. and Europe.

But the opportunities are ample when it comes to working together. Issues like combating democratic backsliding, fighting climate change and countering organized crime demand a joint approach. And the fact that 2025 will mark the first time the Summit of the Americas and the EU-CELAC summit coincide means there will be the chance for all three parties to work together, even as the months ahead will likely hold change—with an election in the U.S., several in Latin America and alterations coming to the EU leadership.

To be sure, not everyone sees closer three-way collaboration as a good thing. With some notable exceptions, most LAC leaders have been clear in establishing foreign policies of active non-alignment. They’ve shied away from choosing a side in increased U.S.-China competition and have developed their relationship with Europe as a third-way means to diversify their external power associations. With this in mind, Latin American leaders might aim to keep their relations with Europe and the U.S. separate.

Policymakers in Washington and Brussels may also bristle at the suggestion of working together when dealing with the region. The U.S. has long had a unique relationship with Latin America, while European leaders like Macron and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen have pursued deliberate strategic autonomy on the world stage. The two powers have their own complex relationship and some significantly diverging positions on critical matters, such as Cuba and migration. And for Latin American leaders, greater unity among Western countries may not necessarily be worth it if it comes with a loss in leverage. But harsh times demand unified responses, and when it comes to the solutions Latin American leaders seek, from increased investment for the digital or green transition to greater security assistance in combating organized crime, ambition and openness to joint action are vital.

Election year, Trump and China

This year could bring further complications. A return of Donald Trump to the White House, as well as the elections in Latin America and new appointments of all three of the leading European institutions, could each spell danger for both the EU-U.S. relationship as well as a constructive agenda with regards to the Western Hemisphere.

The end of the Spanish presidency of the Council of the EU will likely mean LAC returns to the back burner of the bloc’s foreign policy priorities; meanwhile, domestic U.S. politics may reflect on Washington’s foreign policy as the Biden administration takes a stricter stance on authoritarian regimes in Cuba and Venezuela.

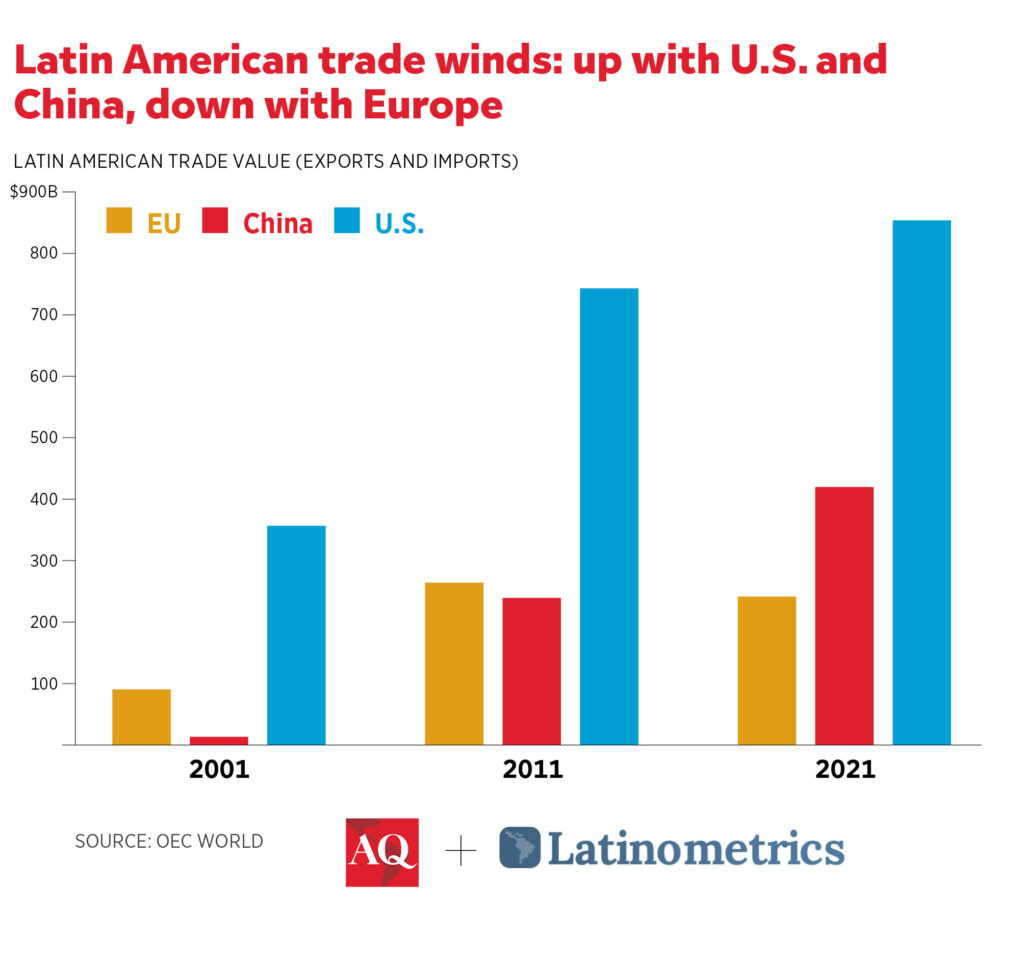

China has become the top trade partner of most of Latin America’s largest countries, displacing the U.S. and Europe from their positions of historical dominance. While Beijing represents a point of contention in U.S.-EU relations today, when it comes to Latin America leaders from both sides of the Atlantic have been wary of China’s inexorable rise. According to the most recent trade study by ECLAC, trade between China and LAC surpassed $14 billion in 2000 and almost reached $500 billion in 2022.

The U.S. actively seeks to maintain regional influence as its global competition with China intensifies. Meanwhile, the European Union has also attempted to remain competitive with Beijing in Latin America as it has lost ground to its so-called systemic rival in regional trade and financing. Both powers seek to shore up their commercial credentials with LAC’s economies while facing little domestic appetite for free trade agreements.

Organized crime

Where do things stand in Latin America with regard to some of the priorities of the U.S. and Europe—like protecting democracy and combating organized crime?

U.S. and EU policymakers have been steadfast backers of regional democratic consolidation in recent months, including in Brazil in 2022 and last month in Guatemala, while Brussels has played its own role in promoting political dialogue between Nicolás Maduro’s regime and the opposition in search of an end to the ongoing crisis.

The conflict against cartels has seen far less progress. Concerns over organized crime have rarely been as relevant or high on the agenda, and the global cocaine market spiked globally just last year. The U.S.-led war on drugs has largely failed and has been widely rejected in the region, most recently by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Colombia’s Gustavo Petro. At the same time, cooperation initiatives such as El PACcTO have seen limited gains.

To this day, no significant coordinated U.S.-EU policy against organized crime in Latin America exists, even as the crisis continues to escalate to new proportions. The Community of Police of the Americas (Ameripol), created in 2007 but granted an international legal personality only in November 2023 with EU support, could provide the necessary forum for triangular cooperation against organized crime. The EU and the U.S. could deepen their collaboration through data sharing, joint police operations, and trilateral investigations. Ecuador, Latin America’s current crime hotspot, would be a perfect venue, as the country has proactively called for international support, and so far only received $1 million in emergency security equipment by the U.S. and a promise for more help on the way.

Over two hundred years ago, the U.S. implemented the Monroe Doctrine brazenly to keep European powers out of Latin America. Yet, in a twist of irony, today, the U.S. is best served by inviting cooperation with the modern-day equivalents of these same European states as it seeks to make regional progress on democracy promotion, fighting organized crime, and contesting China’s influence. A modernized, triangular cooperation between Latin America’s countries and its natural partners in Brussels and Washington might strike that balance.