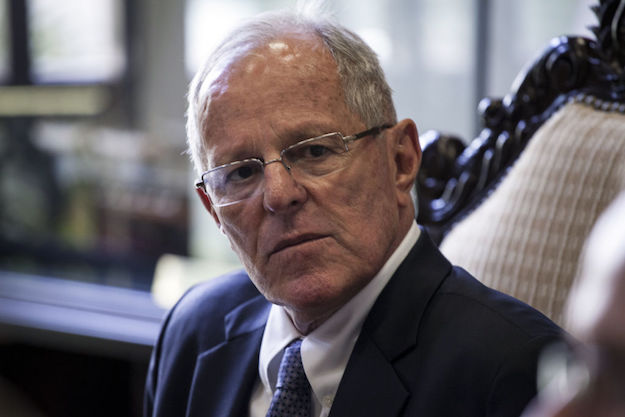

The specter of impeachment hanging over Pedro Pablo Kuczynski this week raises an important question about Peru’s politics: Why are the country’s presidents prone to crisis, political volatility and unstable mandates?

The answer lies in a democracy that has yet to fully mature. Whether or not Kuczynski is impeached on Thursday, Peru’s parties and political institutions are in desperate need of reform.

Kuczynski is suspected of taking payments from Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht during his time as prime minister and finance minister under former President Alejandro Toledo over a decade ago. Congress voted 93 to 17 on Dec. 15 to back a proposal to debate Kuczynski’s dismissal for “moral incapacity” on Dec. 21. If they approve his ouster, it would be the fourth time in the country’s history that a president is removed on such grounds, the last one being Alberto Fujimori in 2000.

His removal would be a shock. PPK, as he’s known, has only been in office for 16 months. Investors had welcomed him, coming as he did in the wake of the left-leaning administration of Ollanta Humala. His presidency has been viewed as business-friendly, and his cabinet has included some high-level names, including Alfredo Thorne, a former JPMorgan economist as finance minister, Carlos Basombrio, a well-respected consultant and sociologist as minister of the interior, and Mercedes Araoz, a former finance minister as second vice president. The country’s economic prospects have been improving. This positive momentum could come to a quick halt if the country enters a period of major political turbulence, as appears likely.

Of broader concern are the implications for democracy and political institutions in Peru. Democracies in Latin America are young, and Peru is no exception. In some cases, the removal of poor leaders may be justified. But the repeated removal of elected officials more often points to institutional weakness, rather than strength. PPK has been personally accused of involvement in corruption. But there are deeper reasons that his administration is in trouble.

First, political parties in Peru are largely new and notoriously weak, little more than vehicles to carry candidates through the election process. PPK’s Peruvians for Change is based on his initials (Peruvians Para el Kambio, with Kambio purposely misspelled). Keiko Fujimori’s Popular Force party also seems to have a single goal: get her elected president. In fact, her first initial appears in the party logo.

Since PPK assumed the presidency, following a narrow victory over Fujimori in 2016, his relations with the Popular Force have been strained. PPK’s party holds just 18 seats in Congress, compared to Fujimori’s majority of 71 out of 130 seats. While both parties occupy a similar space on the political spectrum – their economic platforms aren’t far apart – Popular Force has caused major problems for PPK’s administration. Several ministers have been run out of office, some perhaps on spurious allegations, and Congress has been highly obstructionist. It appears as if Fujimori’s party would like PPK’s administration to fail for the express purpose of catapulting her to the presidency in 2021, the date of the next scheduled election, if not before.

Not surprisingly, Fujimori’s party is unanimous in its support of PPK’s removal – even though their own offices were recently raided by Peruvian prosecutors investigating Odebrecht connections. Some view the current proceedings against PPK as the Popular Force’s attempt to carry out a coup with the express aim of destabilizing the country and the PPK administration, and perhaps leading to early elections in which Fujimori could become president. (In fact, the process to remove PPK appears to be an especially fast one.) None of this signals a healthy party system or mature democracy. Robust political parties are able to survive an individual’s victories and defeats. This is still not the case in Peru.

The second reason why PPK’s presidency is at risk has to do with the structure of Peru’s political system. A president with just 18 representatives in a 130-seat Congress composed of six parties is unlikely to enjoy the conditions needed to run a successful administration. This type of fracture creates incentives for pork, patronage and illegal vote buying. Peru, along with other countries in the region whose Congresses share these characteristics, should consider rules that require parties to earn a certain percentage of votes nationally in order to gain seats.

The immediate implications of PPK’s plight are worrisome. Should he survive the impeachment proceedings, his presidency will be – at best – severely weakened, and the legitimacy of his government questioned. His current approval rating, in the mid-20s, would likely continue to slip. The political environment will remain tense, with opposition parties blocking his agenda on a variety of fronts.

If PPK is removed, Peru will enter a period of great uncertainty. The most likely scenario is that his vice president would take over. However, if his first and second vice presidents refuse the office – perhaps in a show of solidarity – early elections would result.

If new elections are called, a populist outsider would stand a decent chance of winning. Peruvians are fed up with their political class, and it’s not hard to see why. Consider the last several presidents of Peru, prior to PPK (leaving out the president that completed Alberto Fujimori’s term upon his removal): Ollanta Humala was jailed as part of a pre-trial detention for corruption charges involving campaign funds from Odebrecht; Alan García is currently a target of several probes involving money laundering and corruption; and Alejandro Toledo is living in the U.S. as a fugitive, accused of taking $20 million in bribes from Odebrecht (PPK has asked the U.S. government to extradite him). Alberto Fujimori himself has been in jail for a decade on human rights abuses, embezzlement, and other charges.

The potential removal of PPK, someone who had been viewed as someone above the fray, could have troublesome repercussions, given Peru’s weak party system and poor political institutions. The next few months could put Peru’s democracy to the test.

—

Rosen has 20 years of experience in the Latin America financial markets, at both leading investment banks such as Goldman Sachs, and asset managers including Trust Company of the West. He has lived and worked in both Argentina and Brazil.