With its recent transformation from fringe technology to mainstream commodity, 3D printing has been hailed as the next Industrial Revolution. The ability to design and manufacture goods at low costs could fundamentally change the way we produce and consume.

Although still in its infancy, the 3D printing revolution has already transformed our daily lives—from 3D-printed shoes and clothes to custom-printed exteriors and interiors for green, low-energy cars such as the Urbee. But some of its most transformative applications have been in healthcare, where there is now a capacity to print living tissue and some kinds of replacement organs.

You don’t need to be an expert in 3D modeling to take advantage of the innovative technology. With access to a 3D printer, numerous resources are now available to the lay person. For example, www.thingiverse.com offers thousands of free, community-generated models for download. Once a model has been loaded into special software—Cura and Repetier are two of the most popular, and are also free—the user just has to press print and watch as the 3D printer slowly builds the model one thin layer at a time. The object is created with melted plastic that passes through a hot extruder as the printer moves in three dimensions—a process that can take from 15 minutes to 12 hours, depending on the size of the object being printed. While printing a model is easy enough, it takes some experience to consistently print accurate models.

Although 3D printing technology has been around for 30 years, it has only recently become accessible and affordable enough for true innovation. Just seven years ago, a printer could cost as much as $250,000; today, it is possible to purchase a fully assembled and calibrated printer for less than the cost of a laptop.

Medicine is one area where the benefits of this technology have been immediately clear. Medical device companies were one of the early adopters of 3D printing technology, and the printers have been a mainstay at big device companies, hospitals and trade shows for years.

View a Q&A with Aaron Oliker, cofounder and chief innovation officer at BioDigital, Inc.

While dental professionals and craniofacial reconstructive surgeons have been using higher-end 3D printers in the U.S. for education and surgical planning since the late 1990s, surgeons have begun printing custom-designed implants for their patients in the past decade.

3D printers have also been used to produce artificial limbs. Robohand—a South Africa-based charitable organization that creates 3D limb models and offers free downloads of their instructions and designs—uses 3D printers to generate featherweight custom arms, hands and fingers at lower costs than traditional prostheses: $500 to $2,000 instead of $10,000. As an added bonus, their designs work with the motion of existing joints to mechanically move the custom-made prostheses and do not require battery power or microsurgery to connect the nerves to the device.

View a slideshow of medical 3D printing images here.

The concept of obtaining 3D models from digital assets may have a profound effect on the future of medicine. BioDigital, Inc., a company that has been labeled “the Google Earth of the human body,” has created the BioDigital Human—a 3D interactive environment containing over 5,000 anatomically correct structures, plus simulated disease conditions for men and women. The system has a wide range of applications—from patient and surgical education to yoga instruction and medical device marketing. And it’s possible that, in the near future, the 3D models in the BioDigital Human will be printable and will aid in the design and development of anatomy-based inventions, such as Robohand’s prostheses.

While most off-the-shelf printers typically produce rigid plastic models, it’s also possible to augment a standard 3D printer to print flexible materials such as NinjaFlex, a more flexible plastic polymer. Many high-end printers can produce a gradient of different materials to simulate the feel of skin, soft tissue or bone.

Recently, medical researchers have also been experimenting with a material called bio-ink to print living soft tissue, skin and organs. Bio-ink is composed of living cells in a process developed by Gabor Forgacs, a biological physicist at the University of Missouri, to grow blood vessels and cardiac tissue. While cells from animals have been used to make blood vessels, using the patient’s own stem cells helps reduce the possibility that the body will reject the tissue. The bio-paper used in printing resembles gelatin, allowing modified printers to extrude anatomical structures such as aortic valves and tracheal splints. Bio-ink is printed in conjunction with a stiff material, such as polylactide (PLA)—a biodegradable polyester—to establish the shape for the tissue structures.

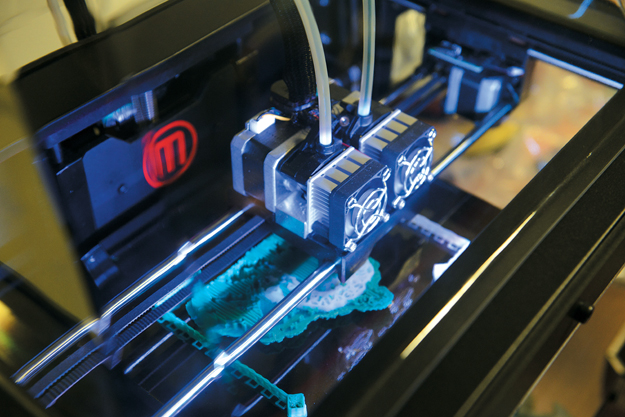

Researchers at the Manhasset, New York-based Feinstein Institute for Medical Research have successfully used this process to grow the cartilage tissue necessary for a replacement trachea in a two-month-old child suffering from a collapsed airway, by using an experimental MakerBot Replicator 2X 3D printer with a dual extruder: one extruder printed the PLA scaffold and the second lined the PLA with bio-ink.

Feedback from surgeons allowed the researchers to quickly create different variations—over 100 iterations in one month—of the model until a viable model for the surgery was produced. Once the final model was approved, it was placed in a bioreactor to allow the cells to grow.

In the next decade, innovative use of 3D printing in medicine is expected to address a wide range of health conditions by creating customized solutions that were previously too expensive or too difficult to produce for an individual patient. As this technology continues to evolve and become more affordable, and as innovative companies continue to provide free or low-cost models that can be easily printed anywhere in the world, our view of what is possible will continue to expand. We have only now begun to explore how this technology can improve our health.

Slideshow images courtesy of Adam Torres, Art Director, BioDigital, Inc.