The Captain of Industry | The Musician | The Entrepreneur

The Educator | The Oil Expert | The Politician | The Economist

The Humanitarian | The Rights Advocate | The Foreign Leader

This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro. | Leer en español

A career in the upper echelons of the global oil business has landed Gustavo Baquero in Norway, but his thoughts — and much of his tremendous energy — remain focused on his home country.

“Mentally, I’m in Venezuela every day,” he told AQ, apologizing for the enthusiasm that turned our first interview into a lively two-hour conversation. “I’m in a constant state of, ‘How can I contribute?’”

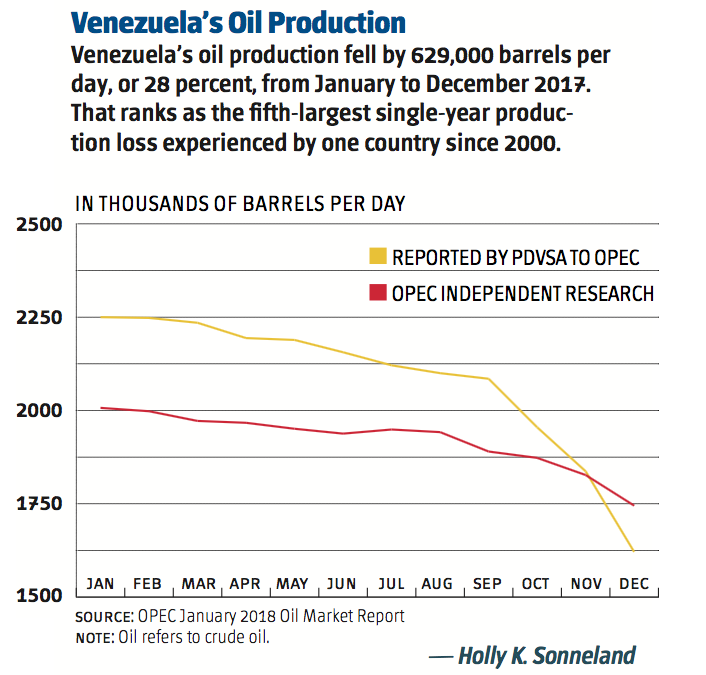

Baquero is obsessed with the Venezuelan paradox: His country has the world’s largest proven oil reserves, but its people lack food and medication. His expertise means he’s well placed to diagnose what ails the beleaguered oil sector, which is producing at the lowest rate since the 1980s. Above all, he is full of ideas on how to fix the problem — and move forward.

In Venezuela Energética, or Energetic Venezuela, a book he co-wrote with prominent opposition leader Leopoldo López, he does just that, starting with a proposed change in the country’s relationship to its energy resources.

“It really is inconceivable, the relationship between the riches of the earth and the way people are living. We have gotten to the stage where Venezuelans hate oil,” he said. “We need to make oil our servant, not our master.”

Although Baquero, the son of a prominent family of doctors, was raised in Caracas and built a career in the oil sector, the idea of a book about Venezuelan oil policy was only born around 2012. That’s when he and López, a lifelong friend, realized that although their country was utterly dependent on the commodity that makes up 95 percent of its exports, it had no long-term policy in place.

No one had attempted to develop such a strategy for Venezuelan oil since 1956, when former President Rómulo Betancourt published his oft-cited work, Venezuela, Política y Petróleo. Since then, the world has changed drastically: The threat is no longer peak-oil (a scenario in which the world runs out of oil and production drops) but peak-demand (in which demand drops as cleaner energy options become available).

Timing is of the essence. Venezuela needs to produce at a maximum, and fast, Baquero said. Most long-term forecasts suggest oil demand will rise for approximately 20 years, but even that is probably optimistic.

“I know my grandchildren will have a very difficult energy landscape,” Baquero said.

Other actions hastened the decline of the state oil company, PDVSA. In 2003, Hugo Chávez fired 18,000 workers, nearly half its workforce, for protesting the company’s politicization. This meant that right as the commodity’s price spiked, Venezuela had few managers and experts in the field. Production stagnated; PDVSA, and Venezuela, never recovered. The government also forced new contract terms on foreign companies, and started pouring barrels of oil into petro-diplomacy and domestic subsidies.

As Baquero researched the book, the political landscape in Venezuela was changing fast, with the economy spiraling out of control. Chávez died in March 2013. His successor, Nicólas Maduro, clamped down on the opposition. López, jailed in 2014 while leading anti-government protests, had to scribble notes for their book on napkins smuggled out during family visits. Meanwhile, the price of oil tanked, taking with it what was left of the Venezuelan economy.

Although the country has 20 percent of the world’s oil reserves, it now produces less than 2 percent of global oil supply.

Despite all this, Baquero sees several potential paths to recovery.

The first part of his plan is to maximize production. Based on his research and on historical oil production records — during the early growth of 1943 to 1970, then during the aperture of the 1990s, when the country opened its hydrocarbons to private participation — Baquero believes Venezuela could conceivably increase production by 150,000 to 200,000 barrels a day per year, by as soon as 2020. This, of course, assumes a government willing to implement a turnaround plan immediately — highly unlikely under Maduro.

Politics aside, how does Venezuela raise production? The country has repeatedly set production goals over the past 15 years that have never been met. To change this, Baquero calls for a reversal of Chávez-era hydrocarbons laws that diminished returns for international investors. Under a new framework, foreign companies would be more willing to help with a turnaround.

This includes tendering new fields, ideally through an auction system run by an independent and transparent regulator. As in the energy reform underway in Mexico, PDVSA would get to pick prized assets for itself first in a so-called round zero; the remaining fields would be offered up to bidders.

Everything must be done to restore the oil sector to professionalism and transparency, using the best global practices, Baquero said. If that were to happen, he believes many experienced and committed professionals would be ready to return home.

Next, PDVSA should direct resources away from the country’s notoriously extra-heavy crude and invest instead in conventional oil and natural gas. Venezuela now imports thousands of barrels of oil a day to dilute heavy crude, when it has 40 billion barrels of conventional crude in reserves. It also has 200 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, the most in South America. Venezuela could pipe its gas to Trinidad, which has LNG export terminals, and become a natural gas hub.

Another problem facing Venezuela is that, in a state-controlled economy greased by oil proceeds, society becomes reliant on government spending. To fight this, Baquero proposes creating a sovereign wealth fund similar to Norway’s. It would allow citizens to draw from a fund fed by oil profits to address the humanitarian disaster, and pay for education, health care, housing and pensions. Norway’s fund, two decades old, is already worth $1 trillion.

Baquero borrows other ideas from Norway, stressing the need for economic diversification, and for the development of a clean energy matrix. As for the existing pacts that tie up Venezuelan oil shipments for years to come, Baquero proposes honoring them — after pressing for a renegotiation. Slashing domestic subsidies that can make gasoline cheaper than water must go, though it would be politically challenging, he said.

“It’s an absurd waste of money that does not benefit the poor,” he said.

Only PDVSA — professionalized and depoliticized — remains untouchable in his remake of the oil sector. Privatization, he said, is “not in discussion.” This is only partly because it is politically unviable; at this stage, the company is in shambles and worth little of its potential value.

At the end of our second phone call, the conversation turned personal. Baquero mentioned he is an avid marathon runner, with 14 races to his credit. He’s attracted to “the discipline, the challenge, the prize of getting over the finish line,” he said.

Then we returned to the topic of home. Would he like to work in a future Venezuelan government?

“Of course! It’s a dream of mine,” he answered.

It’s a good thing, I thought. Venezuela will need his ideas, but it’ll also need his marathoner’s stamina.