The Captain of Industry | The Musician | The Entrepreneur

The Educator | The Oil Expert | The Politician | The Economist

The Humanitarian | The Rights Advocate | The Foreign Leader

This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro. | Leer en español

Families whose arrested loved ones have disappeared. Protesters who emerge from a night in jail with a broken arm or leg. Opposition politicians locked up on bogus charges.

The victims of chavista justice number in the hundreds of thousands.

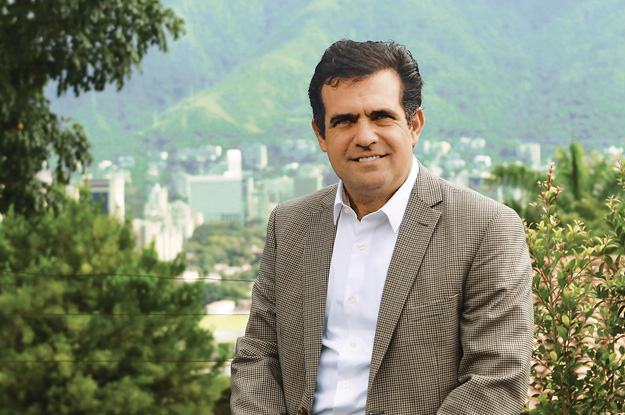

And for more than 15 years, Alfredo Romero has been their champion.

Romero is the executive director of Foro Penal, a nonprofit organization of more than 150 attorneys and 4,000 volunteers whose job is to keep track of political prisoners and offer legal services to anyone who has been arbitrarily detained or tortured by the government.

Increasingly, Romero said, the regime’s targets include disgruntled members of the military — President Nicolás Maduro’s ostensible base of support.

“There are many people who want change,” Romero, 49, told AQ.

Romero’s turn as one of the leading advocates for Venezuelan human rights and justice came almost by accident. After studying law in Caracas, he earned a master’s degree in Latin American studies from Georgetown University and another in banking law from the London School of Economics. He was set for a career in project finance — and even wrote a book on the subject.

That all began to change on April 11, 2002, after a failed coup against then-President Hugo Chávez. The ensuing clashes between pro-government forces and protesters left 19 dead, including 18-year-old Jesús Mohamed Espinoza Capote. Romero was introduced to Espinoza’s family through a mutual friend, and helped them file suits before the Supreme Court and the

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Soon, others started coming to Romero for help — including wounded protesters. In response, Romero and his colleagues began offering them free counsel. “We thought it was a project that would end that year, but it was only the beginning,” he said.

That project evolved into Foro Penal, today one of Venezuela’s largest civil society organizations.

In addition to its advocacy work, Foro Penal provides other organizations with precious reliable data about Venezuela’s courts. According to its latest count, authorities have jailed more than 12,000 people for politically motivated reasons since 2014; at the time Romero spoke with AQ in early February, the government was holding 231 political prisoners.

Justice for political detainees is likely to remain elusive under the current regime, Romero said. With little public support, Maduro’s only means of retaining power is repression. The justice system is stacked with government loyalists, and independent-minded judges face possible imprisonment if they defy the executive branch.

When a democratic transition does come, Romero believes it would be possible for Venezuelan institutions to rebound quickly. He said local laws are “very well written,” and the system still retains many qualified judges who are able to operate impartially if they are guaranteed independence.

“It’s a matter of guaranteeing that judges won’t be fired if they take a different opinion from the government,” Romero said.

Judges who have committed crimes in recent years, such as using their office to persecute political adversaries, would need to be evaluated individually, Romero said. But he warned against any plans for a large-scale purge. “What we cannot do is what Chávez did at the beginning, where he removed all the judges and created his own rule of law.”

He also suggested that Venezuela could set up an independent, international legal body similar to Guatemala’s International Commission against Impunity to oversee legal aspects of a change in government. Civil society groups such as Foro Penal could also play a role, he said.

Until that transition comes, Romero and his colleagues are keeping a more narrow focus: “Our goal is to increase the political costs of repression.”

—

Renwick is a journalist based in New York