This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on youth in Latin America.

In economics it’s known as a demographic windfall—when, in the course of a nation’s development, diminishing birth rates mean fewer hungry mouths to feed relative to the number of young people in their working prime, with still comparatively few retirees living off the country’s reserves.

It’s a dynamic that should be paying big dividends in Latin America today: Fertility rates in the region have fallen by more than half in the last 30 years, while 15- to 24-year-olds make up more than 20 percent of the region’s population for the first time in history.

But Latin America’s window for demographic-driven economic growth is closing quickly, and the region has yet to make the most of its opportunity. Part of the reason is that, despite rising youth unemployment and dwindling productivity, governments still spend too much meeting obligations to the old and too little investing in the young.

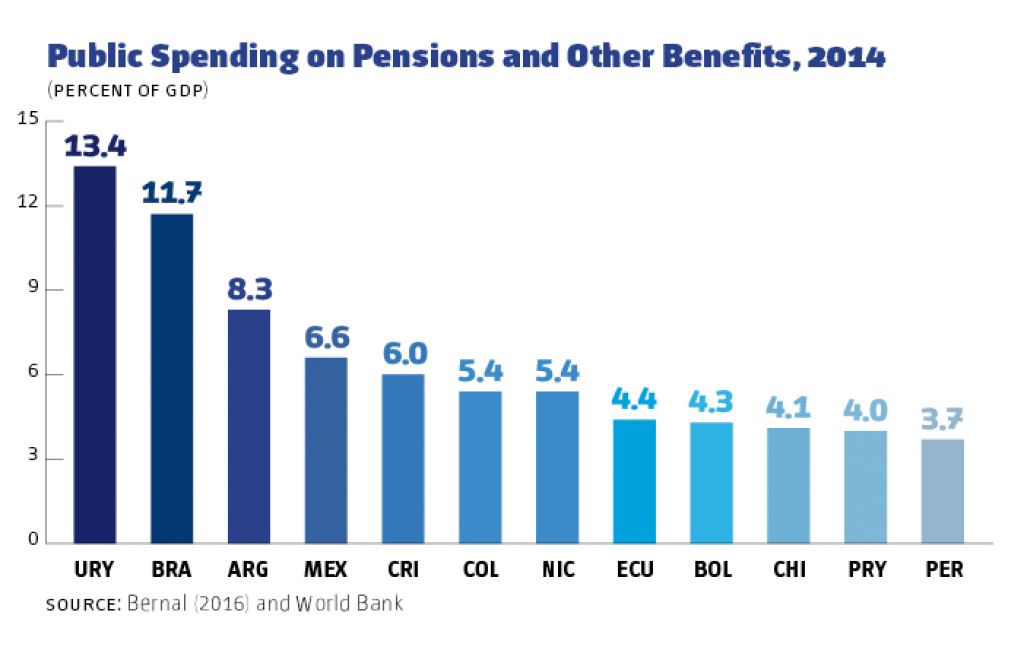

It starts with pensions. Some of the largest economies in the region dedicate an excessive share of their budgets to pensions and other benefits for the elderly, leaving the young with a smaller piece of the pie.

Uruguay and Brazil clearly stand out, as their public pension expenditures exceed by far the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of about 8 percent. Argentina is slightly above the OECD average as well, while Mexico spends about the same as the United States (6.9 percent).

Lower rates for countries like Peru and Bolivia are also misleading, since they usually just mean lower coverage rates for the eligible age group. If these countries were to try to raise their coverage rates, public pension spending would likely increase to levels seen in Argentina, Brazil and possibly Uruguay.

Nor is current public pension spending particularly effective. Coverage is distributed unevenly across income levels, with higher-salaried and higher-skilled workers benefitting the most. The lack of pension coverage for low-income workers, especially those employed in the informal sector, has prompted some countries in the region to introduce pensions for the elderly—even if they never contributed to the pension system in the first place. These pensions are financed from general government revenues, and they cost, on average, about 0.5 percent of a country’s GDP (with widespread variations). Although they serve a critical role in reducing old-age poverty, these pensions further divert resources from Latin America’s youth — resources that could be spent on preventive health care, social programs or, especially, tools to access the labor market.

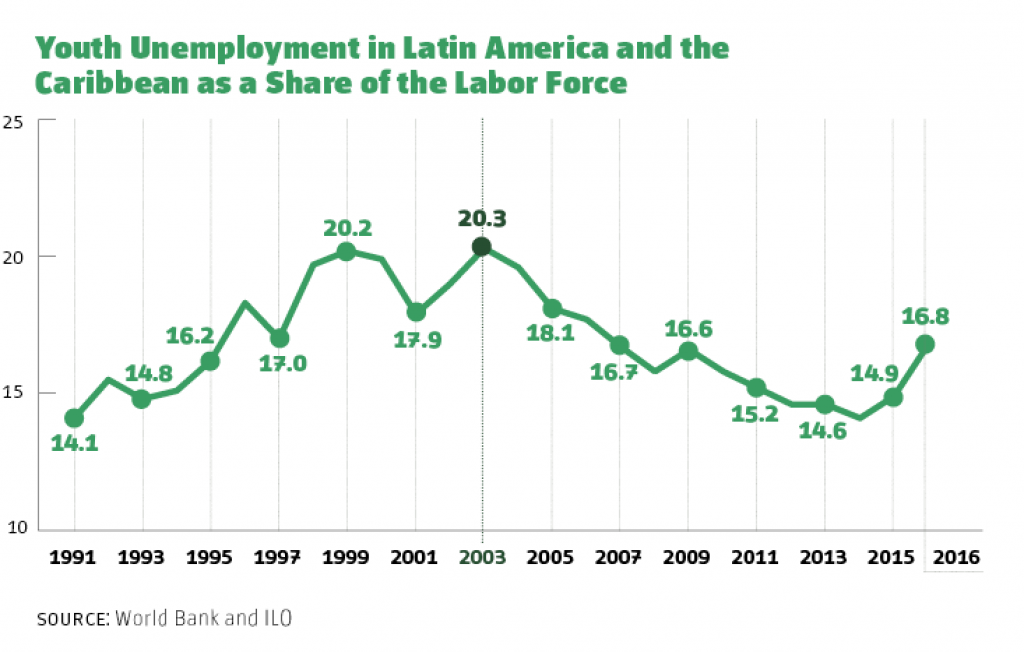

Despite Latin America’s general macroeconomic improvements over the past 25 years, for many countries in the region the number of young people without a job has actually increased over the past two and a half decades. Brazil, Uruguay, Costa Rica and Colombia now top the list with youth unemployment rates above 20 percent of the total labor force.

And there are reasons to believe it’s going to get worse. Following a sharp rise between 1991 and 2003, youth unemployment in Latin America fell back to 1991 levels by 2014, mostly as a result of strong regional growth that has since subsided with the end of the commodities boom. Youth unemployment has since shown a dramatic increase, and political and economic uncertainty in the region, especially in Brazil, Argentina and, to a lesser extent, Colombia, isn’t likely to help matters.

This dynamic has a widespread dampening effect on the region’s economies. One World Bank study showed that for most countries in the region, youth unemployment deducts, on average, more than 0.4 percentage points from annual growth. At the individual/household level, youth unemployment leads to forgone income of between 26 and 46 percent over a working lifetime. Put differently, young Latin Americans who struggle to find jobs will generally go on to earn lifetime incomes that are only three-quarters or even half of what they would have earned had they been gainfully employed early on.

Despite this, governments spend too little helping young people acquire the skills they need to secure available jobs. According to an OECD study, around 50 percent of firms in Latin America say they have difficulty filling open positions; 32 percent use foreign talent to find the skills they need. But quality and enrollment rates in the region’s schools lag well behind much of the rest of the world, and public spending on vocational training—an important tool for linking education with entry into the work force—averages just 0.4 percent of regional GDP.

More should be spent on apprenticeship, education and training programs that match young people’s skills to market demand. But one-to-one cuts on spending for the elderly would not be a complete solution; social security and pension reform, if properly executed, would help reduce the cost of obligations to the old without stripping them of protections they need. In countries like Brazil, for example, simply establishing and enforcing a minimum retirement age could free up resources to invest in the young. The region’s track record on this type of reform isn’t encouraging, but the long-term consequences of a discouraged and underprepared workforce should not be ignored. Failing to act will mean a less prosperous region for young and old alike.