Like Alejandro Jodorowsky himself, Albina and the Dog-Men seems to be all imaginable things at once: a fable and a folktale, a Western, a tragedy, a lewd comedy. A love story.

The short novel’s titular character is an albino giant with no memory of her past. By moonlight, Albina unwittingly transforms the men of a dusty Chilean town into ravenous dogs, hungry for violent sexual satisfaction that only she can provide. Unable to avoid the monsters she has created — and the one she has become — Albina sets off on a labyrinthine journey in search of a cactus that, we are told, holds the power to end her affliction.

Albina is joined in her pilgrimage by Crabby, a bearded recluse of a woman who gives her shelter in the opening pages of the story. Crabby has undergone a transformation of her own: As a child obsessed with Paul Féval’s The Hunchback, she bent herself over and pointed her feet outward, “accepting the idea of being an aggressive crab separated from others by a hard shell.” Nobody ever corrected her posture.

For Jodorowsky, the novel’s repeated transformations are both literal and spiritual. His characters are led — at turns by tragedy and at others by love — to examine the identities they have designed for themselves. At one point, Albina, faced with the prospect of giving up a life that is cursed but also familiar, exclaims that “ceasing to be what she is” both horrifies and terrifies her. The question is whether she will confront the illusion of her “self” just the same.

In signature fashion, Jodorowsky — the Chilean-born son of Ukrainian immigrants — bends perceptions of history, culture and geography, forcing his readers to question their surroundings. Crabby and Albina journey through remote deserts and forgotten jungles that shift and undulate as if viewed dozily from a car window. Along the way, they are forced to outrun or outwit, in no particular order: a clubfooted tax collector, snakes, a cunning Inca shaman, drug dealers riding giant rabbits, and a group of lecherous Himalayan monks.

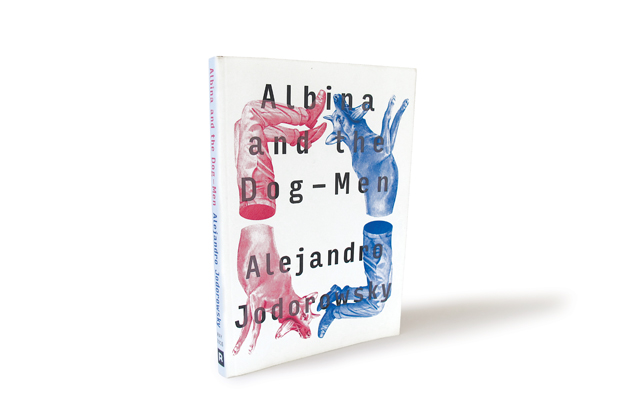

As the assemblage of surreal adventures implies, Albina and the Dog-Men moves more like one of Jodorowsky’s celebrated comic books than a traditional novel (the edition is, in fact, illustrated by comics artist François Boucq). The language is instantly visual, and Alfred MacAdam’s deft translation is whimsical and fantastic without drifting into adolescence.

Albina and the Dog-Men is the product of an unfathomable, affecting imagination, of an auteur whose creative works include five novels, 10 films, countless pages of poetry, aphorisms, comics and plays, and a handful of self-help books on psycho-magic, the tarot and geneology. This not to mention a starring role in a documentary — Jodorowsky’s Dune — about a film he didn’t make (though, in a sense, it made him).

The novel, perhaps more so than Jodorowsky’s other work, could be called amusing. But it is not intended as distraction. The 87-year-old looks to gain philosophical ground on his readers at every turn. For some, Jodorowsky’s reach will exceed his grasp, and they will be left with an odd, if entertaining, mythology. But those looking to Albina and the Dog-Men for something more long-lasting may find themselves transformed — at least until the next full moon.

—

Russell is an editor for AQ.