Guatemala is the only Latin American country that suffered genocide in the twentieth century. More than 200,000 people—the vast majority of them indigenous Maya civilians—were murdered, mostly at the hands of the military, during the decades-long civil war that began in the 1980s.

Guatemala’s war officially ended in December 1996 with the signing of a United Nations–brokered agreement. But although political violence has declined, more Guatemalans meet violent deaths each year now than at the height of the conflict. And unlike that conflict, in which most of the deaths occurred in remote areas of the countryside, today’s lethal violence occurs for the most part in Guatemala’s urban areas.

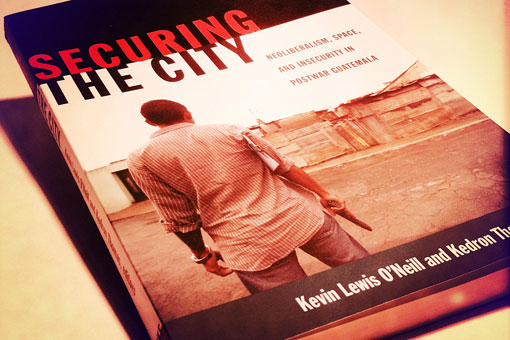

This changing dynamic—the subject of an anthology of essays titled Securing the City: Neoliberalism, Space, and Insecurity in Postwar Guatemala—is a consequence of widespread social violence linked to poverty, inequality and the deep hold of organized crime on the Guatemalan state and society. As Manuela Camus of the Gender Studies Center at the Universidad de Guadalajara points out in her chapter, Guatemala City is now “one of the most violent spaces in one of the most violent countries in the world.”

The book’s editors, University of Toronto assistant professor Kevin Lewis O’Neill and Harvard University doctoral candidate Kedron Thomas, have collected contributions from an international group of anthropologists to explore through ethnography the ways in which Guatemalans experience and adapt to this changing, precarious and dangerous environment. They analyze how contemporary social and economic dynamics play out in the lives of ordinary people in Guatemala City through the lens of anthropologists who closely consider the effects of neoliberalism.

In a stimulating introduction, O’Neill, Thomas and Thomas Offit of Baylor University argue that life in Guatemala City today is marked by neoliberal paradigms of governance.

This ideological and structural orientation, they claim, exists throughout the world and has three main effects: increased inequality in income distribution and reliance on unstable, precarious forms of income generation; heightened concern with security and a consequent loss of trust in the state’s ability to provide safety; and stepped-up privatization of public spaces. According to the authors, comparing Guatemala City to places that suffer similar degrees of social inequality, crime and urban violence, such as Johannesburg and Rio de Janeiro, provides a critical window on the ways in which neoliberalism works and how the local population reacts to its supposed effects.

One cross-cutting theme is the increased privatization of security and the growth of a culture of self-reliance. As the editors note, “The spike in violence in the postwar period has prompted not public debates about the structural conditions that permit violence to thrive in the first place, but rather a new set of practices and strategies that privatize what would otherwise be the state’s responsibility to secure the city.”

Rather than the strengthening of the state, which was supposed to follow at the end of the war, what has occurred is the devolution of law enforcement to private firms and communities. The social contract between government and society has been replaced by a fragmented patchwork of legal and illegal self-help initiatives, including community-organized policing, the growth of the private security industry and “social cleansing” of suspected delinquents.

A second theme—brought out in chapters by Deborah Levenson of Boston College and Camus—is the erosion of the professional urban middle and working class. As a result, Guatemala City lost a key constituency that believes in a modernist, statist notion of progress and development. The city previously offered possibilities for personal advancement, autonomy and reinvention, but today inhabitants of urban neighborhoods see life getting worse, not better.

They also increasingly blame young people for violent crime. As Camus observes, “The neighborhood’s young men have gone from being their community’s hope to being understood as a threat and a danger.”

There is also an ethnic dimension to these transformations, reflecting Guatemala’s deep history of racism and segregation.

The increasing number of Indigenous residents in Guatemala City—Mayan migrants from the countryside are now approximately 25 percent of the city’s population—have destabilized established economic and racial hierarchies. In interviews with the authors, many of the poor, non-Indigenous middle- and lower-class city dwellers blame these “out of place” Indigenous migrants for the violence and crime that affect their everyday lives.

A third theme in the book is the patterns of rural and urban economic restructuring in Guatemala. Using new research, authors analyze these patterns and reach the conclusion that, despite multiple forms of physical and economic insecurity, there have been many winners in this new neoliberal urban environment.

In a fascinating chapter, Offit tells the story of Don Napo, a successful Mayan entrepreneur who runs a street-trading shoe emporium in downtown Guatemala City and has become a “retail king.” Napo, who migrated to the city in the 1970s, found a niche in the shoe market to start a family-based business operated by family members and workers from his hometown in the western highlands. One of the keys to his economic success is the social solidarity created through deep linkages within the Maya community. This allows him to “appeal to the youths’ family ethos to ensure loyalty as he represents his interests as theirs, though they have no formal ownership stake.”

In this book, as in similar publications, ethnographic approaches to understanding neoliberalism face inevitable limitations. For example, there is little analysis here of the ways in which new forms of violence serve Guatemala’s ruling class (which now comprises traditional elites and organized crime).

There is also an unfortunate unevenness in quality across the chapters. Yet despite these drawbacks, the editors and contributors to this volume do an excellent job of revealing how the urban poor are stigmatized and criminalized, illustrating the “neoliberal logics of space, security and citizenship” referred to in the chapter by Rodrigo J. Véliz and O’Neill.

This work will help guide the discussion and debate on how neoliberalism has contributed to social upheaval and dislocation in Latin America and beyond.

Clearly, the challenge of finding more inclusive and democratic forms of urban renewal that can provide economic and physical security for the inhabitants of Guatemala City—and many other cities across the world—has yet to be met.