This article is part of the Leaders of Social & Political Change series from the Fall 2012 issue of Americas Quarterly. View the full special section.

In 1962, the Ford Foundation quietly began work in the Southern Cone. At the time, the predominant economic model in the region, import substitution industrialization, was struggling to keep up with the expanding demands for political and economic development. Tensions were surfacing from the unmet social demands of unions, farmers’ groups and the middle classes. The years of economic growth, the U.S.-initiated Alliance for Progress and broader access to education had sparked many of these new groups—and with them, competing interests and needs.

The social and political turmoil resulting from military coups across the region—from Brazil in the mid-1960s to Uruguay, Argentina and Chile in the first half of the 1970s—curtailed freedom of thought and research in the social sciences. The rebirth of social science and the return of scholars to those countries coincided with the return of greater political space and activity—and eventually, of democracy.

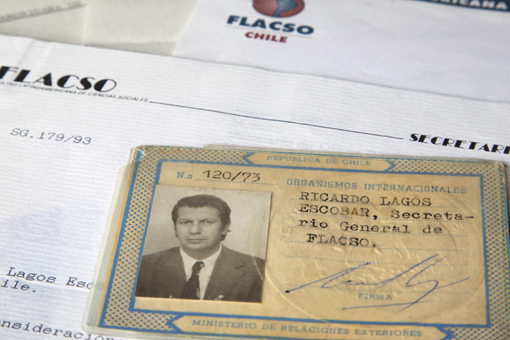

In the Southern Cone (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay), the field of social sciences really started to take root in the late 1950s and accelerated in the early 1960s. In large part, this was due to the development of national universities such as the Universidad de la República in Uruguay, La Universidad Nacional in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and the Universidad de Chile, in Santiago, Chile. International agencies also played a role, such as the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Latin American and Caribbean Institute for Economic and Social Planning (ILPES) under the auspices of ECLAC, and the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO), founded in the late 1950s. By the second half of the 1960s, FLACSO had already become an important touchstone for social science in the region through the work of Alain Touraine and José Medina Echeverría at ILPES and ECLAC.

The work of other intellectuals also began to assume regional and international prominence, shaping the research and political discussions of the time. Of note was the work of Aldo Solari in Uruguay and of Torcuato and Guido di Tella, Gino Germani, and others in Argentina. It was at this time that a young Brazilian sociologist, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, made his appearance in Santiago as a young professor in exile after the coup in Brazil.

It was in the post-coup environments in the Southern Cone, as military governments tried to snuff out independent thought by intervening in universities and shuttering independent research centers, that international agencies such as the Ford Foundation proved crucial.

As soldiers attacked labor unions, arrested and tortured suspected adversaries, closed down or censored independent media, and clamped down on academic institutions, NGOs and research programs stayed open and continued their projects under the protection of international agencies. Ford’s financial support and moral backing is where the foundation truly made its mark. We all learned in that era to look respectfully at this institution that bet on preserving the ability of social scientists to think.

It was through these laboratories of social and political research (as much within the institutions as in the streets outside) that people like Guillermo O’Donnell began to understand the emergence of the bureaucratic authoritarian state and its context. Others began to consider the interrelations of the demographic explosion, the inability of economies to adapt to rising expectations, and the need to develop a more scientific approach to population studies—such as a comparative research project that brought together eight academic centers and was supported by the Ford Foundation, among others. The contributions of the Ford Foundation, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and others, such as the development agencies in the Netherlands and Germany, cannot be understated.

The local groups that cropped up and supported these efforts provided the essential local momentum. These include the Corporación de Estudios para Latinoamérica (CIEPLAN) in Chile, the Instituto Torcuato di Tella in Argentina, the Fundação Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, and the Centro Brasileiro de Análise e Planejamento (CEBRAP), which Cardoso expanded upon returning to São Paulo. Ford’s support also allowed FLACSO to establish its headquarters in Buenos Aires and open offices in Brazil, Ecuador and Mexico.

The flame of independent thought was kept alive by international visionaries and organizations like the Ford Foundation. They understood that to cultivate a fully developed democratic system, there must be space and capacity to analyze, reflect and understand societies and the world around them. It was that space and those opportunities that allowed democratic thinkers and eventual leaders of the democratic movement to survive and flourish— individuals such as Guillermo O’Donnell, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Juan Carlos Portantiero, Enzo Faletto, Julio Cotler, José Matos Mar, Orlando Fals Borda, Alejandro Foxley, Oscar Muñoz, Ricardo French-Davis, and others.

Fifty years later, the tasks are different, as are the challenges facing a Latin America that is emerging strongly from the global crisis yet still hampered by inequality and exclusion. This Latin America has greater confidence in its potential and a large middle class with new demands of its own.

Today, the Ford Foundation and many others continue the work they set out to do five decades ago, supporting spaces and institutions so that social scientists can continue understanding and contributing to their respective countries. What we have achieved in this part of the Southern Cone is a result of the work of many—especially those that made it possible for thought, in spite of the circumstances, to continue to forge new paths.