LA PAZ — With regional relations worsening since 2019, Bolivia is now facing fresh upheaval in the relationship between La Paz, the political capital, and Santa Cruz, its economic motor. But as demographic trends change the balance of power between these two powerful cities, along with their internal makeup, this clash looks different from previous ones.

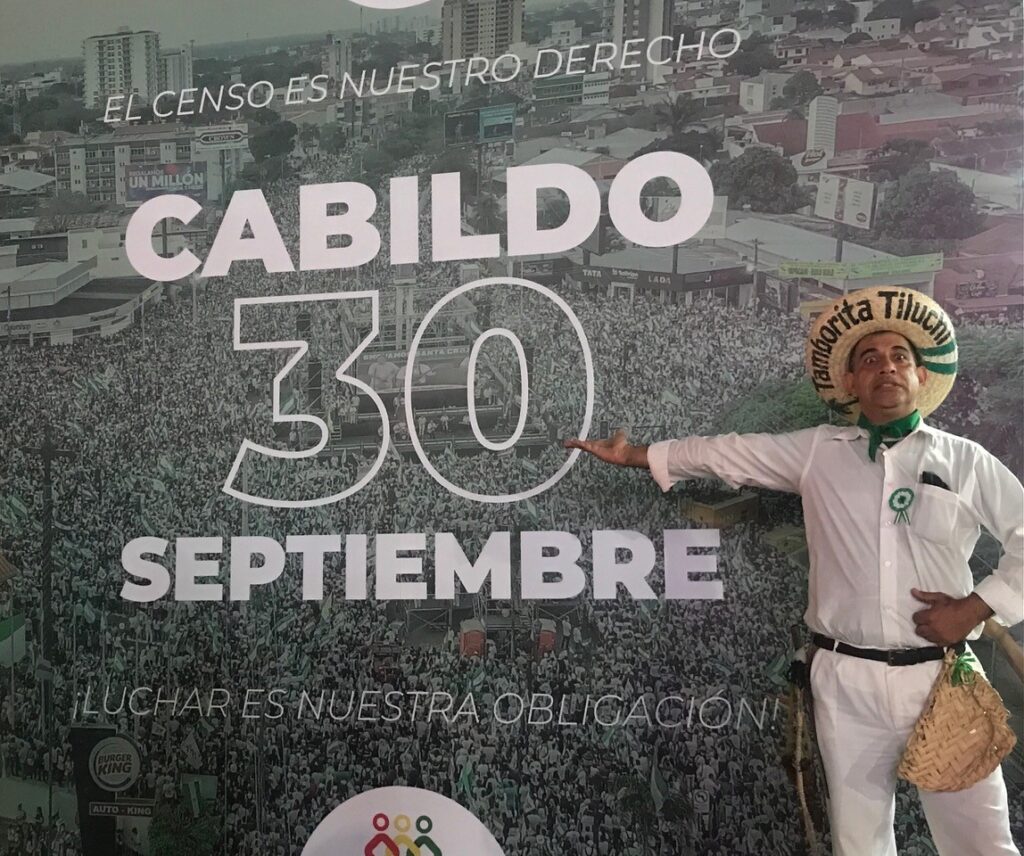

It started when the government announced that a census scheduled for November would be delayed until 2024. Fernando Camacho, governor of the department of Santa Cruz, announced the first of two civic strikes, calling on cruceños to block roads and shutter shops. The government didn’t budge. Now Camacho has called a meeting of civil society for September 30 to decide how to ratchet up the pressure.

That Santa Cruz’s governor has chosen to take a stand on the census reflects its importance. Resources from the central state and representation in the national parliament are determined according to the population of each department and its municipalities. Since the last census, in 2012, it’s clear that Santa Cruz has grown substantially. The government says the delay is for technical reasons, but cruceños see an attempt to deny them the resources and parliamentary seats that they deserve.

But this clash is just the latest installment in a long narrative of back-and-forth between the two cities and the regions they represent. This cleavage has divided Bolivia for decades and often determined the course of its politics. In simple terms, La Paz represents the central state and the western highlands, dominated by mining, with strong Indigenous organizations. Santa Cruz leads the eastern lowlands, with an economy based on hydrocarbons and agribusiness, and where the Indigenous population is smaller and less politically powerful. The divide is not just geographic, but political, economic and cultural. Santa Cruz has long pushed for greater decentralization.

This tension came to a head during the first government of the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), which began in 2006. Evo Morales became president with 54% of the vote, but the opposition took control of the senate and most departments. The government was divided and confronted by a strong coalition. In the lowlands there was talk of separatism. When the situation turned violent and risked spiraling, UNASUR, the regional organization, stepped in to mediate. The government made strategic concessions—for example, incorporating autonomy for departments into the “plurinational state” set out in the new constitution. In the end the constitution was passed, the MAS won the subsequent election with 64% of the vote and leaders of the opposition coalition went into exile.

After its political victory, the MAS ushered in a period of stability by supporting agribusiness in Santa Cruz. It was mutually beneficial: Santa Cruz made money, and the government got trade, dollars and food production for the internal market.

“The tip of the iceberg of that alliance was the decision of the MAS government to expand the agricultural frontier—a measure that clearly favors the cruceño elite,” said Moira Zuazo, an academic at the Free University of Berlin.

Then vice president Álvaro García Linera encapsulated the arrangement in a famous quote: “Businessmen, you want to make money, you want to do business—do it. The government will open markets for you, give you money for technology, support you in any way you want. But stay out of politics.”

This consensus held for a time. But the first cracks appeared in 2016, when Morales defied the result of a referendum on whether he could exceed the constitutional term limits and run again in the 2019 election. Santa Cruz once again led the protest against the MAS—only this time, the discourse was not about regional autonomy but protecting democracy. This would eventually provide the opportunity, in the aftermath of the 2019 election, for Camacho to mobilize protests against the MAS, pressure Morales to resign and flee the country, and back Jeanine Áñez, a little-known senator from Beni, to assume the presidency.

“(The relationship between the MAS and Santa Cruz) was not exempt from tensions, but there was a kind of cohabitation,” said Helena Argirakis, a political analyst and MAS official from Santa Cruz. “Camacho emerged wanting to break this arrangement.”

Áñez was only in office for a year before fresh elections saw the MAS, led by former finance minister Luis Arce, sweep back into power. Shortly afterward, in the 2021 departmental elections, Camacho became governor of Santa Cruz. Since then, La Paz and Santa Cruz have been unable to find a new balance.

Today, Santa Cruz stands alone in its protest over the census. It has not found support from Bolivia’s other eight departments. The mayors of the departmental capitals have also stayed out of it. Even within Santa Cruz, the divisions are visible. Beyond the capital, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the strikes don’t seem to have been closely upheld, especially in rural areas. Though Camacho tried to summon the spirit of the 2019 protests, the call to arms over the census does not have the same mobilizing power.

“Camacho’s leadership was born from polarization. Therefore, he seeks to recreate that original moment to affirm and restore his leadership,” said Fernando Mayorga, a sociologist at the Universidad Mayor de San Simón in Cochabamba. “But there is no longer an opposition coalition as there was before. They are isolated.”

Still, the census—whenever it is completed—will not only show that Santa Cruz has grown: It will show it has changed. Aside from continuing urbanization, the dominant demographic trend in Bolivia is one of migration from west to east. This is blurring the rift in identity between La Paz and Santa Cruz and changing the political makeup of the latter.

Though the migration is yet to show through in the elites that dominate the region’s institutions, it reveals itself in elections, where about half the municipalities of Santa Cruz—albeit rural and less populous ones—are now held by the MAS. The MAS also has 11 of the 28 members of the regional assembly. Not all those migrating east are masistas—but they are perhaps less inclined towards Camacho’s strategy of confrontation with La Paz, and the particular idea of cruceño identity it draws on.

“These people arrived in Santa Cruz,” said Zuazo, “and they have changed it.”

—

Graham is a freelance journalist based in La Paz, Bolivia. He has reported from Europe, North Africa and South America for The Guardian, The Economist and World Politics Review, among others.