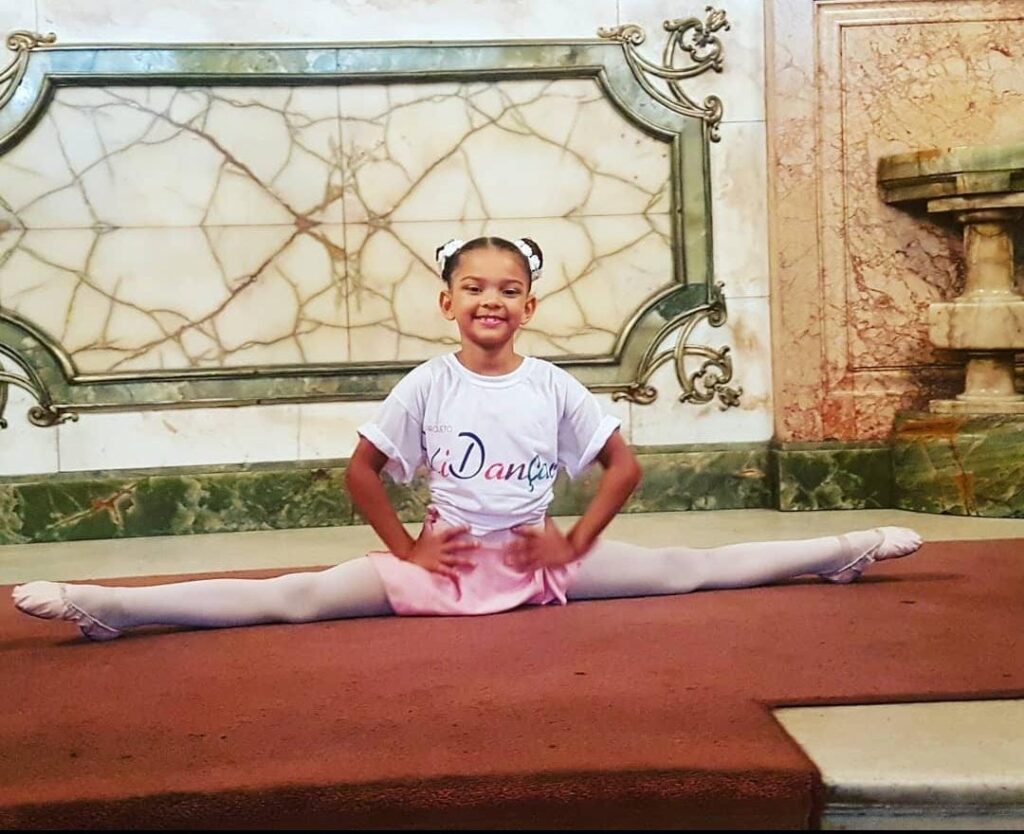

Deep within Rio de Janeiro’s sprawling Complexo do Alemão favelas, tutus and ballet slippers are helping young people stay in school – and thrive. Behind their success is Ellen Serra, an attorney who in 2010 hired a ballet teacher out of her own pocket to give instruction to 10 kids from the community. That idea has since grown to become ViDançar, a social project with over 300 students who pirouette and plié before getting help with their homework and English lessons.

Serra didn’t grow up in Complexo do Alemão, and before starting the program had no prior contact with dance, much less classical ballet. But as a survivor of abuse, both as a child and as an adult, she was looking for ways to heal, and was told that volunteering to assist others might help.

“A close friend introduced me to some amazing people doing social projects in Alemão. Working with them started to bring me back to life and soon I felt like I needed to do more,” Serra told AQ.

Serra thought the discipline inherent in ballet training could give kids living in poor and violent environments a way to imagine a future beyond unskilled labor and the influence of local drug dealers.

Among Alemão dwellers, 69% of teenagers report having experienced violence toward themselves or someone close to them, according to a 2020 study. “These children go to sleep and wake up hearing gunshots. There is also hunger, which is another form of violence,” said Serra.

To have an impact beyond the dance studio, ViDançar stays closely connected to its students’ traditional schooling. Young people in the program have to be enrolled in school and share attendance records with Serra and her team. The project celebrates school milestones, distributing medals and commendations based on report cards. And while the ballet classes are free, parents have to “pay” by showing up for bi-monthly parent teacher conferences, turning the project into a support network for parents as well.

All this has translated into a high school graduation rate of 92% for ViDançar’s students, in a country where more than 60% of people over 25 never finished their studies.

Then there is the ballet itself. At 13, Luis Fernando Rego’s mother drafted him into taking his little sister to ViDançar classes. But then Rego was smitten, too. He joined the class, and quickly his natural talent led to a scholarship to the Bolshoi Ballet school in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. Before turning 19 last year, Rego moved to Denmark as a professional member of the Tivoli Ballet.

“Before joining ViDançar, I didn’t care for school,” Rego told AQ. “What I learned there is that we need education and discipline, because that is what makes a citizen.”

Rego was the first to join an international company, but 30 other ViDançar students have followed in his footsteps, with scholarships to the Bolshoi and other well-known professional ballet schools.

(Photo: ViDançar)

“The project changes lives, not only for us, but for our families,” said Rego. “Our families start to have dreams, to see the world in a different way.”

ViDançar relies on volunteers and contributors, and has secured at least one sponsor to continue paying teachers and staff for the next two years. Serra is now trying to gather support to reach other vulnerable parts of Brazil. She recently started small programs in inland communities in the northern state of Bahia with the same goal: to offer young people a window into a different reality.

“We are going to towns where hunger has been normalized, where kids drink mud mixed in water just so that they won’t feel the emptiness inside their stomach,” Serra said. “We can’t normalize hunger, and hopelessness.”