Beijing’s Military Diplomacy Is Making Major Gains

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America

For years, U.S. officials have warned about China’s growing influence in Latin America and the Caribbean. But since 2010, that reference has been elevated to a new category, as leaders from the Southern Command (Southcom) have consistently identified the competition from Beijing as a “key challenge” in every annual report presented to the Armed Services Committees of the U.S. Congress.

Amid those concerns, the U.S. typically comforted itself by reflecting on its lead in one key area: being the “preferred partner” in defense and security cooperation in the Americas. While in general terms, this remains the case today, that confidence is starting to look shaky as China is beginning to surpass the U.S. in one related field: military diplomacy.

Encompassing international military education and training (IMET), military diplomacy pivots on visits by high-level military leaders to the region, exchanges and dialogues between military colleges and defense universities, and joint war games, exercises and exhibitions. A new dataset compiled by the Center for Strategic & International Studies Americas Program shows China’s substantial ascent in the area of diplomacy with most armed forces in the Western Hemisphere. One case illustrates the trend: In 2020, China had five times as many students from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) enrolled in its military colleges as the U.S.

Military diplomacy can accrue significant soft and hard power advantages. In peacetime, it helps build goodwill, capacity and influence networks within foreign militaries. During conflict, it can enhance familiarity with preparedness levels, doctrine and command, or even underpin interoperability between forces. A cadet who trains abroad often carries that experience into senior leadership, shaping how a country thinks about security, alliances and even arms purchases.

China has always regarded the importance of military diplomacy as a critical element in how it engages with other countries. In LAC, however, these considerations often took a back seat to economic ties. Yet, China’s ambition to extend military cooperation with the region emerged in the Foreign Ministry’s 2008 Policy Paper, and was later reinforced in the country’s 2016 Policy Paper, which stated: “China will actively carry out military exchanges and cooperation with Latin American and Caribbean countries … in such fields as military training, personnel training and UN peacekeeping, [and] expand pragmatic cooperation in humanitarian relief, counter-terrorism and other non-traditional security fields.”

The policy papers explain why, a decade ago, China began a concerted effort to draw closer to LAC in the defense and security domain. It did so by launching the China-LAC High-Level Defense Forum, under the umbrella of the China-CELAC Forum, which deliberately excludes the U.S. and Canada. Over the past 10 years, this initiative has produced white papers and road maps for the region’s defense and security cooperation, while the ties have also thrived under non-traditional paths, such as the start of the China-LAC Military Medicine Forum.

A non-aligned region

In past eras, Southcom was at the leading edge of military-to-military engagements in the Americas. The institution also advanced partnerships through flagship initiatives such as the National Guard State Partnership Program, the Theater Maintenance Partnership Initiative, and the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative Technical Assistance Program. Southcom has also developed extensive international military education and training programs in the Americas.

Thanks to U.S. assistance, the region boasts a wealth of multilateral fora and bodies for defense engagement, such as the Conference of the Defense Ministers of the Americas, the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (formerly the School of the Americas) and the Inter-American Defense College (IADC). The IADC claims it has trained 3,169 students from 29 different countries since its inception—over 27% of whom have reached general officer or flag ranks.

While Southcom maintains a steady presence and the Trump administration has signaled a strong interest in the region, U.S. military diplomacy appears to have declined in recent years. Some of the reasons are familiar—bureaucratic red tape, extensive reporting requirements, and restrictions on the use of U.S. government funds to support education and training programs. Flatlining defense budgets that barely manage to keep up with inflation have also had an impact.

Starting in 2014, Southcom has seen a noticeable decrease in the resources needed to support its mission. In fiscal year 2025, the institution reported over $322 million in unfunded “wish list” items. From this list, roughly one-third is typically allocated to support military training and exercises with LAC partners— exactly the type of military diplomacy at which China has become adept. The unfunded “wish list” is a proxy for missed strategic opportunities to strengthen defense ties with the region and build partner networks.

Research by the Center for International Policy, which publishes the Security Assistance Monitor, demonstrates how traditional recipient countries in LAC have seen a decline in IMET billets. Peru shrank almost four times from approximately 1,000 trainees in the mid-2010s to fewer than 200 in 2019; Argentina fell from over 500 trainees in the late 2000s to just over 100 in 2019.

Beijing has adroitly filled these gaps with IMET opportunities in China. Typically, Chinese IMET offers greater perks to LAC students, including business-class travel, luxury hotels, large allowances and trips for the entire family. In a differentiation from U.S. strategy, which tends to invest in senior officers and those identified as future senior officers, Beijing has offered more opportunities for officers at lower ranks. According to CSIS’s dataset, between 2022 and 2025, military officers from 19 LAC countries attended short-term exchange programs, such as the Senior Commander Course and Latin American Military Officer Seminar for senior officers hosted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) National Defense University.

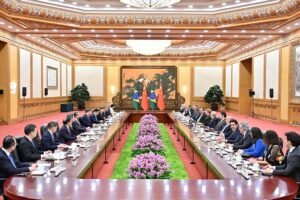

Taking advantage of LAC’s desire to remain non-aligned, China has initiated high-level defense dialogues attended by many in the region. Meetings of the China-LAC Defense Forum, for instance, bring high-level leaders from Beijing into contact with their equivalents in 24 LAC countries. In total, between 2022 and 2025, the period of CSIS’s dataset, China has conducted 119 military exchanges with 19 different countries.

Heavyweights

However, China’s most frequent defense cooperation in LAC has been with South American heavyweights Brazil and Argentina. In Brazil’s case, exchanges span all three military branches—army, air force and navy, and are likely the result of the Joint Commission for Exchange and Cooperation, established in 2004 to enable regular ministerial dialogue and training programs. Bilateral dialogues have also included top-level officials such as the Commander of the Brazilian Army, Tomás Paiva, and the Chinese Minister of Defense, Dong Jun.

In June, before tensions arose with the Trump administration, Brazil went further, assigning both an army general and a navy admiral to serve as defense attachés in Beijing. That level of senior representation is rare outside the country’s ties with the U.S. Brazil’s efforts to position itself in a multi-polar world have also created rare opportunities for China-U.S. interaction in the military arena, such as when both countries participated in Operation Formosa, hosted by Brazil in 2024.

The military exchanges with Argentina also encompass all three branches and are heavily concentrated on educational exchanges. The bulk of the exchanges took place in 2023, a timeframe that coincided with the strengthening of ties between then-President Alberto Fernández and China. Fernández also flirted with purchasing Chinese JF-17 fighter jets for the Argentine Air Force. However, the election of President Javier Milei may be restraining China’s influence, and so far this year, no military exchanges between the two have taken place. Still, institutional defense ties between the two countries remain, and Argentina is also in the process of signing cooperation frameworks on academic exchanges between the National Defense University of Argentina and the PLA National Defense University.

Back to basics

China sees considerable advantages in continuing its inroads in military diplomacy, and its efforts are set to deepen in the coming years with its Global Security Initiative (GSI), which considerably broadens areas of cooperation and fuses security, defense and military cooperation through emerging technologies and climate change and health initiatives.

Given this reality, the U.S. should not underestimate the long-term consequences. Reversing Washington’s declining influence in military diplomacy will require concerted effort. Fully funding IMET and expanding billets for LAC officers at U.S. defense colleges will ensure the U.S. continues to educate and shape the next generation of military leaders in the region. At the same time, the U.S. should pay particular attention to China’s efforts to leverage its military diplomacy into advantages in arms sales, status of forces agreements, greater rotations and even basing agreements.

Three of the region’s largest countries—Argentina, Brazil and Colombia—are Major Non-NATO Allies, providing the U.S. opportunities to deepen cooperation on arms procurement and encourage greater interoperability. In the non-traditional areas of security and defense encompassed by China’s GSI, the U.S. could double down on its historic advantages in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief efforts, where proximity and familiarity are natural advantages.

The U.S.’s more muscular approach to combating organized crime and violence in the hemisphere may also create opportunities for engagement. Countries like Ecuador have been eager to receive greater support in their fight against criminal organizations, while longstanding allies like Colombia face new threats heralded by the proliferation of cheap commercial drones. The U.S. should leverage tools like multinational exercises and joint patrolling missions to empower its allies, weaken the influence of organized crime, and reaffirm its position as the security cooperation partner of choice.

The question is no longer whether China is competing for the hearts of Latin America’s militaries. It’s whether the U.S. is prepared to compete back.