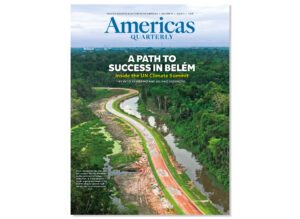

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on COP30 and Brazil | Leer en español | Ler em português

Photos by Alessandro Falco

BELÉM, BRAZIL—At 2 p.m. on a sweltering May afternoon, the air at the famous Praça do Relógio is thick with heat, humidity, and the familiar rhythms of carimbó music pulsing from a vendor’s speaker. Vultures soar above this downtown area near the iconic Ver-o-Peso market, as a construction worker, drenched in sweat, operates a power saw. Its sharp whine pierces through the sounds of the crowd, serving as a visceral reminder: The global climate summit, known as COP30, is approaching.

With just five months to go before the United Nations Climate Change Conference opens in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, Belém is a city in transformation. Dust clouds hover over roads torn up for repaving. Sidewalks are being redone, and cranes dot the skyline. Since the announcement in December 2023 that Belém would host COP30, state and federal authorities, public banks, and companies, including mining giant Vale, have launched 38 infrastructure projects totaling over $1.3 billion, according to local media.

At one construction site near the port, workers labor under the sweltering sun. “We’re about 200 now, but they’re hiring. Another 500 should be arriving soon,” Ricardo Brito, 42, told AQ. Brito was installing handrails and improving the pavement for passengers who would disembark there during COP30. He works for the construction company Pinheiro Sereni Engenharia, which was contracted for COP30-related projects. Not all of them are on formal contracts. “When this is over, we’ll be back on the job hunt,” added his colleague Dorivaldo da Silva, 48. Still, they expressed pride in being part of a transformation they hope will leave a legacy beyond the summit.

Nowhere is the frenetic pace more visible than at Belém’s international airport. Its expansion, budgeted at nearly $85 million, aims to triple its capacity. But it remains open to the public, resulting in an overwhelming mix of noise and dust. Jackhammers compete with loudspeaker announcements as passengers dodge workers carrying planks and paint buckets. Hammering on the roof, a drill roaring nearby, and the whine of saws create a chaotic symphony as hurried couples, anxious elders, and visibly uncomfortable children navigate the modest two-story terminal. Ceiling panels are visibly misaligned, signs of the speed at which everything is moving. Yet for all the dust and delays, the ambition is clear: to prepare the city to welcome leaders from nearly 200 countries.

Under pressure

Farther downtown, a new park along Tamandaré Avenue features one of the most controversial COP30 installations: the “eco-tree,” a metal frame meant to support climbing plants not native to the Amazon. The plants, however, have withered under the relentless sun, prompting online jokes. “Those plants can’t handle this much sun,” said 70-year-old Maria Oliveira, who sells medicinal herbs. Recently displaced from her longtime spot near Ver-o-Peso to make way for renovations, she said, “They moved us, and now our business is hurting.”

Oliveira harvests plants from Belém’s 39 river islands, but extreme heat has changed her work. “I used to restock three times a week. Now, just once. It’s too hot.” COP30, she said, has only added to the difficulty: “We used to sell 10 bundles a day. Now, sometimes, we don’t sell one.” Construction work in the neighborhood has pushed the vendors to a less visible area with less tourist traffic.

The sentiment is echoed by Ricardo de Souza, 59, who sells Amazon nuts. His daily gross sales dropped from $540 in December to $107 in May. Construction disruptions are partly to blame, but climate change also plays a role. Last year’s drought, one of Brazil’s worst, doubled nut prices. The drought affected around 60% of Brazil’s territory, raising the price of energy and affecting agricultural output more broadly. In the Amazon region, it dried up massive rivers, such as the Rio Negro, and left populations dependent on water trucks to access drinking water. It also intensified fires, which destroyed 17.9 million hectares in the Amazon in 2024.

Down at Pedra do Peixe, a riverside port, fishermen lounge in hammocks between shifts. “I came here when I was 11,” said Manoel Trindade, 63. “There used to be more fish, and it wasn’t this hot.” At the nearby market, Maria Loura, 57, another erveira (herbalist), said she has had to reduce her hours due to the heat. “By 4 p.m., I feel like I’m burning. I have to go home, take a shower, and jump in the pool. I built one just to survive.”

Still, she sees COP30 as a needed opportunity. “The world needs fixing. But real fixing. Not just people eyeing our minerals.”

“By 4 p.m., I feel like I’m burning. I have to go home, take a shower, and jump in the pool. I built one just to survive.”

—Maria Loura, 57, an herbalist, poses in the temporary medicinal herb section of Ver-o-Peso. Herbalists are among the market’s most iconic figures, selling traditional remedies deeply connected to Indigenous pharmacology.

Climate conference meets everyday reality

For many in Belém, COP30 is still a vague concept. “I thought it was the Olympics,” said Sara Alexandre, 54, laughing. A lifelong resident, she said climate change is impossible to ignore. “People are fainting from the heat. That didn’t used to happen.”

A federal initiative will add 6,000 cruise ship berths to accommodate guests, mirroring the city’s annual religious pilgrimage Círio de Nazaré, which draws millions. Yet housing prices have already spiked. “Everyone’s moving out to rent their homes,” Alexandre said. “I heard someone’s asking 2 million reais ($358,000) for an apartment. That’s absurd.”

Some are trying to capitalize on the conference. The Faraó Motel, once known for adult films and discreet rendezvous, has rebranded as “Hotel COP30.” Rooms have been redecorated with caiman-themed art, and rates will soar to $1,000 per night. “We’re adapting”, said receptionist Joel Santos, 62.

Layers of history, layers of inequality

Founded in 1616, Belém bears the imprint of centuries of Indigenous, colonial, and immigrant histories. Ancient tools unearthed in the region date back 6,000 years. The city’s neighborhoods still feature 200-year-old Belle Époque buildings with European symmetry, though now corroded by time and tropical humidity. In one forgotten square, a weathered plaque quotes 17th-century Jesuit priest António Vieira, who likened Belém’s surroundings to the Tower of Babel. “There were only 70 languages there, but in the Amazon River, the tongues are so many and so diverse no one knows their names or number.”

Modern Belém is home to 1.3 million people and a renowned food scene, but it faces serious challenges. Just six in 10 residents have access to treated sewage, placing it among Brazil’s worst cities for sanitation. Ana Maria Corrêa, 38, lives beside the Murutucu Canal, where COP30-related sanitation works are underway. “They’re paving the avenue, but our house still has no sewage,” she said. Her neighbor’s house cracked from the vibrations. “The upper floor is sinking,” said Maria do Socorro, 65. No repairs have been guaranteed by Consórcio Canal Murutucu, the consortium responsible for the works outside her house.

“They’re paving the avenue, but our house still has no sewage.”

—Ana Maria Corrêa, 38, who lives beside the Murutucu Canal, sits outside her home. Although the canal is under construction, her house still lacks basic sanitation services.

Elsewhere, in Gentil Canal and Vila da Barca, low-income areas face similar issues. A beloved soccer field is now buried under construction debris. “We don’t play anymore,” said Fernando Carvalho, 23, showing photos from past tournaments.

An environmental paradox

Belém is at the center of Brazil’s climate contradictions. While preparing to host the world’s foremost climate summit, the state of Pará is also home to the country’s largest illegal gold mines, which poison rivers and devastate forests. In 2024, deforestation in this state reached 1,271 square kilometers—almost the size of two New York Cities. Wildfires cloaked much of Brazil in thick black smoke for weeks.

Belém is also seen as a logistical hub in Brazil’s plans to drill for oil in 47 offshore blocks hundreds of kilometers out at sea, in the fragile ecosystem of the Amazon River’s mouth—a biologically rich, poorly studied marine area. In May, Brazil’s environmental regulator Ibama approved the final step before simulated seabed drilling.

“We don’t play anymore.”

—Fernando Carvalho, 23, a local resident, stands where he used to play soccer. The field in front of his home has been transformed into a construction debris site due to COP30.

Back in Belém, another COP30 project—the widening of Rua da Marinha, recently financed by a $45 million loan from Brazil’s development bank BNDES—cuts through a preserved forest. The worksite is a red dirt clearing, with a felled log lying among Amazonian trees. “It’s going farther into the forest,” said a worker, pointing to a stream that will be buried and an açaí grove set for removal. Some of the cleared trees have been transplanted to the City Park, also under construction for the climate summit, including a 15-meter samaúma tree symbolically planted there by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in February.

According to engineer Beatriz Rosa, who oversees Vale’s environmental compliance in the City Park, construction waste is being sent to the Aurá landfill on Belém’s outskirts. There, 21-year-old Henrique Adriano, who has scavenged recyclables since age 10, described life near the dump: “Our street’s impassable, no asphalt, just mud. Cars slide off the road every day. Sometimes the school bus can’t even get through, and class gets canceled.”

“Our street’s impassable, no asphalt, just mud. Cars slide off the road every day. Sometimes the school bus can’t even get through, and class gets canceled.”

—Henrique Adriano, 21, a recyclable waste picker, works at the landfill on the outskirts of Belém.

For Belém, COP30 is both an opportunity and a reckoning. The investments may bring lasting improvements, but also reveal long-standing neglect. The climate conference will spotlight not only global environmental challenges but also the daily realities of the Amazon’s urban poor.

As preparations continue, Belém’s people are bracing for change—hopeful, cautious, and determined to make sure their voices are not lost amid the sound of jackhammers and the promises of progress.