China’s New Playbook for Latin America

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America | Leer en español | Ler em português

China has entered a new phase in its engagement with Latin America.

It is one still characterized by extensive resource-seeking and market-seeking activity, features of the relationship for more than three decades now. As China invests and trades in Latin American raw materials and builds markets across the region for everything from its toys and textiles to ultra-high-voltage transmission lines and cloud services, overall trade continues to rise.

At the same time, the relationship is rapidly evolving toward a more targeted, strategic approach. For all the recent attention given to China’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects, Latin America’s relative share of investments under the plan is falling for the third consecutive year. The region received a little more than 1% of Beijing’s global BRI construction spending and 0.4% of outbound investment in the first half of 2025. Growth in Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region is also slowing.

Whether those trends hold remains to be seen. But the days of Beijing showering the region with loans and large-scale infrastructure projects may be over, or at least diminished, replaced by more deliberate engagement and a focus on specific sectors of Chinese interest, especially at the higher end of the value chain.

The shift in focus among Chinese companies is being driven by a variety of factors and is evident across multiple continents. China’s economic policies are changing amid Beijing’s efforts to achieve moderate rates of economic growth, and so are perceptions of China in Latin America and other parts of the world. Meanwhile, sweeping shifts in U.S. economic and foreign policy under President Donald Trump are actively recalibrating relations between Washington and Beijing—with consequences for inter-American and China-Latin America ties.

Against this backdrop, this would seem a pivotal moment to reassess the evolving China-Latin America relationship, one that calls on Latin American governments to craft forward-looking policies attuned to new trends. It may also lead Washington, which has sought to counter Beijing’s influence in the region, to think critically about the effectiveness of its own strategies and the extent to which they align with current realities.

A new phase

The China-Latin America relationship is defined as much by continuity as by change. China’s demand for the region’s natural resources, ranging from extractives to agricultural goods, continues to fuel China-Latin America trade, which reached $518.47 billion in 2024, up 6% year-on-year. China was the destination for about a third of the region’s mineral exports in 2023. The region supplied approximately 75% of China’s total soybean imports and nearly all (98%) of China’s imports of lithium carbonate in 2024.

Latin America has also long been a vital market for Chinese goods. Even as China’s exports to the region declined 2.4% in 2023, Chinese electric vehicle exports to Latin America grew 55%, according to China Customs data, totaling $4.2 billion. Exports from China to Latin America climbed again—by 13%—between 2023 and 2024, including sizeable sales of high- and low-tech goods. Mexico, Colombia and other countries have also continued to import substantial quantities of industrial machinery, telecommunications equipment and consumer electronics from China, contributing to steady export growth in those sectors. Moreover, if U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods persist, Chinese exports could increasingly be diverted to Latin American markets.

Additionally, China’s outreach to Latin America and other regions has for years been closely linked to its domestic economic agenda. The BRI, launched in its earliest form in 2013 and extended to Latin America in 2018, was as much a tool to address China’s structural economic challenges, such as excess construction capacity and steel production, as it was a diplomatic or foreign policy initiative. Around 2013, as the BRI began to take shape, and as global commodity prices fell, China’s engagement with the region concentrated on large-scale infrastructure projects—frequently financed by Chinese banks and executed by Chinese construction companies.

China’s food and energy security priorities, along with its broader growth agenda, remain central to its engagement with Latin America. But numerous factors, including lessons learned by both Chinese and regional actors, are redefining the contours of the relationship. These shifts are particularly evident in Chinese capital flows to the region, as Chinese companies zero in on sectors of strategic importance to Beijing while increasingly pursuing new, localized avenues for deal-making across the region.

The mitigating effects of Chinese domestic economic policy

China’s recent push to sustain moderate economic growth—despite headwinds such as weak domestic demand, demographic pressures, and high debt—has reshaped its overseas engagement and, by extension, the priorities of the BRI. Alongside domestic stimulus measures, Beijing is seeking greater market share in high-end technologies in both developed and developing markets, including Latin America. At the same time, Chinese banks and companies are in many cases adopting a more cautious, risk-sensitive approach to engagement with the region, while seeking new avenues for deal-making.

This shift is evident in a recent decline in China’s overseas lending to the region and the slowing of its FDI. Once a defining feature of the China–Latin America relationship, sovereign lending, often in support of major infrastructure projects, by China’s two main development finance institutions (DFIs)—the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (Ex-Im Bank)—has slowed dramatically. Between 2019 and 2023, the region received an average of just over $1.3 billion annually from these banks, down sharply from the 2010 peak, when CDB alone extended nearly $25 billion to regional governments. In 2023, according to the Chinese Loans to Latin America and the Caribbean Database (Inter-American Dialogue/Boston University), lending was limited to just two loans to Brazil, totaling $1.3 billion.

Multiple factors help explain the decline in Chinese DFI lending to Latin America and the Caribbean. A key driver has been China’s reluctance to extend new credit to Venezuela, which has accounted for nearly half (49%) of all Chinese DFI finance to the region since 2005. Beijing’s patience with Caracas has eroded amid sustained security and economic risks in the country, and neither CDB nor Ex-Im Bank has issued loans to Venezuela for the past nine years. Lending has also slowed to other major recipients, such as Brazil and Ecuador.

At the same time, demand for Chinese finance has diminished in parts of the region. Jamaica, for instance, has received 10 Chinese loans since 2005, but its successful effort to reduce debt-to-GDP ratios by 40 percentage points in just five years has lessened the government’s appetite for new borrowing. Jamaica’s last DFI loan from China was in 2017.

China’s own domestic priorities further constrain overseas lending. Beijing has directed state banks to concentrate more on supporting growth at home, while companies abroad rely on other sources of finance for priority smaller-scale projects. New rules introduced in 2023 by the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA)—a State Council body overseeing banking and insurance—impose stricter risk management standards that are likely to continue to mitigate China’s external financial activity. In 2025, the NFRA also introduced new market risk management guidelines for China’s commercial banks, including Bank of China and ICBC, both of which remain active in Latin America. While not aimed specifically at overseas lending, the rules, and the signal they send, are reinforcing a more cautious, risk-averse approach to cross-border finance.

Alongside declining sovereign loans, China’s FDi in Latin America has also slowed. Data from the Inter-American Dialogue indicate a downward trend in Chinese project announcements in recent years, reflected in tapering greenfield FDI and a sharper decline in mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Growth in Chinese M&A first slowed in 2014 and has steadily fallen since 2020, based on a five-year moving average.

New areas of focus

Despite a slowdown in finance and investment, Chinese companies remain active in Latin America, focusing on smaller, targeted investments in strategic sectors such as lithium, high-tech goods, and information and communication technology (ICT). China is seeking to manufacture in the region in some cases, including electric vehicle factories in Brazil and auto parts companies across Mexico, all of which rely on imports of components from China. In other instances, Chinese companies are aiming to be primary suppliers of wide-ranging technological equipment and services. Investments in safe cities projects, solar parks, and transmission projects incorporate Chinese technologies and standards and facilitate the exportation of China’s high-tech goods. These and other deals align closely with Beijing’s priorities for high-quality, innovation-driven growth, driving a shift toward selective engagement both regionally and globally.

Recent analysis by the Inter-American Dialogue demonstrates the extent to which China’s investment in Latin America is focused on so-called “new infrastructure” (新基建), a term evoked most recently by Premier Li Qiang during the 2025 “two sessions” as a key component of China’s economic strategy. The term generally encompasses those industries—telecommunications, fintech, and energy transition, for instance—that Beijing considers to be broadly innovation-related.

“New infrastructure”

In Latin America and the Caribbean, investment in “new infrastructure” industries has grown over time, with ICT (including Huawei offerings across the tech stack), renewable energy technology, and, increasingly, electric vehicles accounting for the bulk of this activity. “New infrastructure” industries, including electric vehicles manufacturing, such as the battery, car, and bus manufacturing taking place in Mexico and Brazil; other high-end manufacturing, including medical and machinery manufacturing; ICT; renewable energy investments, such as solar parks in Argentina and Chile and dams across much of the region; and urban infrastructure, including the still slow-to-develop Bogotá metro project, accounted for 58% (around $3.7.billion) of total annual Chinese FDI in the region in 2022 and over 60% of the total number of FDI deals announced by Chinese companies that year.

To be sure, talk of large, China-backed infrastructure projects persists in Latin America. Chinese, Peruvian, and Brazilian officials are said to be discussing the Twin Ocean Railway with renewed interest. Brazil and China signed an agreement to launch a technical, environmental and economic feasibility study for the project in 2025. Initially promoted by Chinese officials in 2014, this project would traverse Peru and Brazil, navigating complex terrain and likely extensive public opposition. Even the long-defunct Nicaragua Canal continues to feature in China-Latin America discourse. In November 2024, at the XVII China-LAC Business Summit, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega sought support from China for a new proposed canal route. Other big-ticket projects—most prominently the massive Chancay Port in Peru—are considered notable examples of China’s enduring interest in large infrastructure development, but they arguably reflect earlier phases of China’s engagement in the region. Study of Chancay began well ahead of CO.SCO’s 2019 purchase of 60% of the shares from Volcan. New Chancay Port-adjacent projects are likely to materialize, however, capitalizing on port-driven growth.

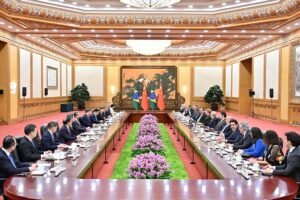

In general, though, China’s focus, whether overseas or at home, is still on bolstering growth and market presence in often high-tech industries. This focus is apparent even in Chinese high-level talks with Latin America leaders. During Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s visit to China in May 2025, China announced plans for a new wind, solar, and energy storage hub from CGN Power and a commitment from Great Wall Motor to invest approximately $1 billion into Brazilian car manufacturing plants, among other deals. Tsingshan Holding Group’s plans to invest $233 million in a lithium iron phosphate plant in Chile were announced during Chilean President Gabriel Boric’s recent visit to China. And President Xi Jinping’s November 2023 talks with Peruvian President Dina Boluarte, Uruguay’s Luis Lacalle Pou, and Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, as well as his April 2023 meeting with Lula, focused on expanding already extensive trade relations, while also encouraging cooperation in mostly innovation-related sectors, including urban mobility systems in Colombia, pharmaceuticals in Uruguay, digital economy, energy, and mining in Peru, and 5G in Brazil, among other areas.

At home, China would appear to be doubling down on this course of action, advancing supply-side policies for high-tech and high-end manufacturing to boost China’s economic prospects. These policies persist despite the drawbacks of “involution,” or Chinese company price competition that compels businesses to continuously cut prices, which are the subject of much deliberation in Chinese policy circles. Still central to China’s approach is what Xi has called “new quality productive forces,” or the pursuit of high-tech, high-efficiency, and high-quality to bolster economic growth. Just this year, China’s Government Work Report reiterated the importance of developing “new quality productive forces,” focusing on high-tech, high-efficiency, and high-quality growth models, in pursuit of a “modernized industrial system.”

Local engagement

Amid this shifting landscape, people-to-people connectivity—one of the Belt and Road Initiative’s stated objectives—is another growing focus for China’s planners, whether in support of diplomatic goals or commercial ventures. In pursuit of local government buy-in for municipal (e.g., smart cities) or other projects, to bypass national-level complications, or as part of China’s often-decentralized approach to aid distribution, much of China’s engagement is being carried out locally, through a tangled web of overlapping interactions and a kaleidoscopic cast of characters, with government, Party, quasi-governmental, and commercial actors all playing prominent roles.

Local level engagement also features in China’s efforts to promote “new infrastructure” across Latin America, and to acquire the lithium and other tech-related minerals and metals. China’s provincial level investments in Argentine lithium are now well-established, but in the case of Jujuy, efforts to access those resources date back to a 2010 MOU between Argentina’s Geological Mining Service (Segemar) and China Geological Service (CGS), promoting scientific exchange and capacity-building workshops. In 2015, then-President Cristina Kirchner and Chinese President Xi extended this partnership, formalizing joint research and training initiatives. And, beginning as far back as September 2017, CGS, Segemar, and the National University of Jujuy conducted geological studies to assess the industrial potential of Jujuy’s salt flats.

Long-standing local initiatives are underway elsewhere, too, to establish markets, facilitate strategic deal-making, and advance policy coordination, in addition to other objectives.

“Uncharted waters”

The effects of the many trends underway in the China-Latin America dynamic—on the region, on China’s economic interests, and on the standing of other regional partners—are still unfolding, and will continue to be shaped by a range of factors, including ongoing shifts in Chinese economic and foreign policy, regional responses, and U.S. efforts to counter Beijing’s engagement.

China’s “new infrastructure” initiatives have been embraced in many parts of the region, given their alignment with regional development priorities, particularly in energy transition, climate adaptation and digitalization. But whether and to what extent the region benefits from China’s increasingly targeted engagement will largely depend on regional approaches to resource governance, technology transfer, and the development of robust legal and regulatory frameworks for emerging technologies.

At the same time, China’s policy measures may take a toll on its relations with parts of the region. Already, China’s industrial strategy—including efforts to offload excess capacity in Latin America and other markets—has encountered some resistance in the region. Steel tariffs by Mexico, Chile and Brazil reflect this dynamic, while Brazil’s January 2024 electric vehicle tariffs signaled concern over surging imports from China. Pressure on Latin American manufacturers may very well increase as China seeks to boost competitiveness in sectors such as medical equipment and machine tools, where some regional firms remain active.

Chinese assessments of Latin America’s viability as a market and partner will also continue to shape future decision-making. The overseas activities of Chinese companies are being monitored more closely as Beijing “braves uncharted economic waters” and “ventures into dangerous shoals,” as the 2024 3rd Plenum “decisions” document puts it. While China remains committed to engagement across the region and to cultivating new markets and partnerships, firms are likely to follow paths of least resistance—either by focusing on receptive localities in Latin America or by shifting attention to other regions. As it stands, Latin America is capturing a decreasing share of China’s BRI investments, accounting for just 1.14% of construction projects and 0.4% of overall investment in the first half of 2025.

For all stakeholders—including the U.S., which remains committed, in theory, to limiting China’s influence in the region—it will be critical to grasp both the trajectory of the China–Latin America relationship and the pace of its evolution. At present, the U.S. risks missing the forest for the trees, so to speak, by focusing too narrowly on a subset of mostly national security-related Chinese projects or an outdated vision of the BRI. China’s engagement is dynamic—aligned with evolving industrial policy and economic security objectives—and, if successful, intended to establish a dominant market position for China across strategic industries, while nurturing the sorts of bilateral trade relations that ensure some degree of political alignment with Beijing. The U.S. game of whack-a-mole in Latin America—or a piecemeal, reactive approach to derailing select projects of concern—is unlikely to meaningfully alter this trajectory and is straining U.S.-Latin America relations. There is a pressing need for a comprehensive, clear-eyed assessment of China’s progress and priorities—one that resists a static view of China’s global interests, interrogates the scope and limits of U.S. competitiveness across domains, and upholds the centrality of inter-hemispheric partnerships in advancing shared objectives.